Words from Louie Palu and Sanaz Mazinani

Two artists featured in We Are Story share creative insights about themselves and each other.

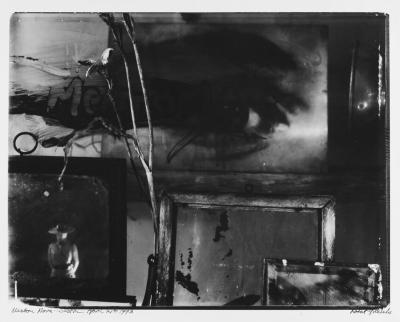

Louie Palu. Medevac helicopter on mission over Zhari District, Kandahar, Afghanistan, July 23, 2010. pigment print, Overall: 50.8 × 61 cm (20 × 24 in.). Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase, Canada Now Photography Acquisition Initiative, with funds from Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas Metivier, 2021. © Louie Palu, courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery 2021/53.

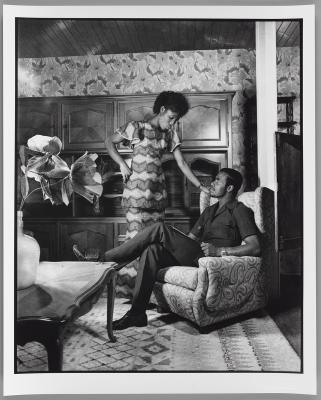

Since January 2023, the group exhibition We Are Story: The Canada Now Photography Acquisition has been on view at the AGO (galleries 128 and 129), showcasing the vitality and range of contemporary Canadian photography. Featuring recent works by asinnajaq, Raymond Boisjoly, Aaron Jones, Lotus Laurie Kang, Robert Kautuk, Gabrielle L'Hirondelle Hill, Sanaz Mazinani, Jalani Morgan, Louie Palu and Dawit L. Petros, this exhibition is curated by AGO Curatorial Fellow Marina Dumont-Gauthier with Sophie Hackett, AGO Curator, Photography.

In late April, Louie Palu and Sanaz Mazinani joined Dumont-Gauthier for a conversation about their respective practices. Although their work varies greatly in presentation, thematically, the two share many similarities.

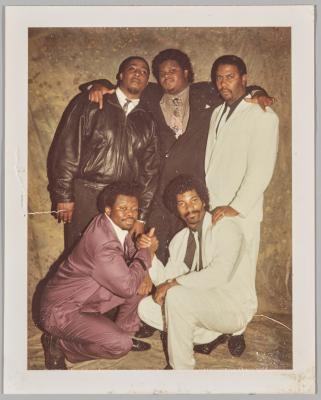

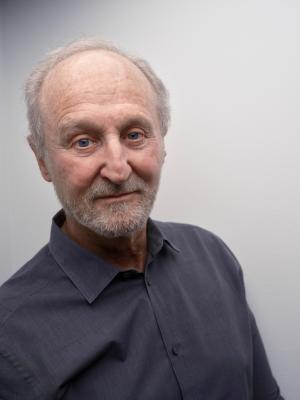

Palu is a documentary photographer and filmmaker whose work focuses on social-political issues such as war, human rights and poverty. His work has appeared in festivals, publications, exhibitions and collections internationally. His project covering politics in Washington from 2019−2021 was selected for a World Press Photo award.

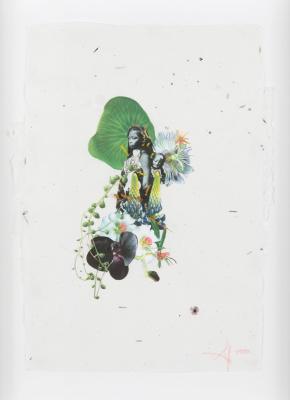

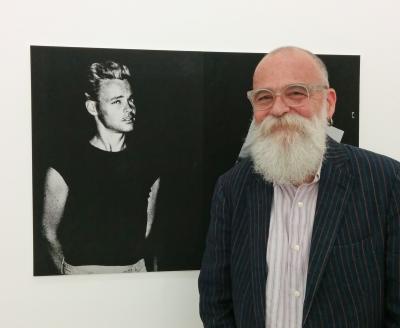

Mazinani is an artist, educator, and curator. Working across the disciplines of photography, sculpture, and large-scale multimedia installations, Mazinani creates informational objects that invite a rethinking of how we see, suspending the viewer between observation and knowledge. Informed by the visual rhetoric and staggering presence of contemporary media, her practice aims to politicize the distribution of images, invite critical reflection, and draw attention to social justice and environmental movements.

We connected with Palu and Mazinani to find out more about their approach to creation, their works in We Are Story, and the ways in which their practices reflect each other.

Foyer: In your Fighting Season series you documented so many powerful and captivating moments. Considering all your time in Afghanistan, could you share one of your most significant experiences with us?

Palu: In 2008, the soldiers I was on a combat operation with one evening were ambushed by the Taliban and the fighting was quite heavy. An anti-tank weapon fired, and the shell exploded directly behind me which knocked me to the ground. The concussion of the blast affected my hearing, and I was stunned. For three hours, the soldiers continued the attack, and we came up to a horse tied to a building, and it was blocking our way (a different horse than the one in my photo in the exhibition). The officer in charge yelled at me to calm the horse down so we could pass. I ran up to the horse, grabbed the rope, and caressed his cheek, whispering to her (him?) until it stopped bucking and frantically moving around. I did not untie it, fearful it would run out into the line of fire. The battle ended and I am not even sure I got any photos after the blast that stunned me.

Foyer: The photography you create covers a broad range – portraiture, landscape, action and more. Can you walk us through your process for deciding what to photograph and when? Is it more intuitive or structured?

Palu: In an active fighting situation, you can have a plan (I always did) of what you are looking for and then there are times where all hell is being unleashed and you get what you can, or nothing at all. I am constantly trying to push beyond conventional news photography; I like to break tropes. Cinema and painting in many ways inform the way I think. Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro had a theory about light which I subverted to think about drawing and painting without a pencil or brush. There can be subtle confluences in photography of tools such as focus, grain (or pixels), light and shadow that become imperfect to the eyes of many. This is best exemplified in my image of the wounded soldier in the blue light. For me, it’s the most perfect imperfect photo. Technically so many things are going wrong, just like the war. Additionally, there is the tree photo, which is the ever-present force of nature dwarfing the soldier but is a response or echo of the Group of Seven. I like to ask questions: what is bigger or smaller in our identity as photographers and Canadians, nature or war? Coming back to your question and my answer, the tree photo was taken in total calmness, and the blue man was at night right after a bomb exploded near our helicopter and we were flying at 180 miles per hour to a field hospital.

Foyer: What do you find moving about Sanaz Mazinani’s work? What are the main similarities you perceive between her practice and yours?

Palu: I think – in a literal sense – depending on who you are, our work is very similar. Conceptually, we are responding to war, violence and both of our family histories related to trauma and war. Forces of violence and state control in a macro sense we can all see in photographs framed by whatever tools we use, whether it is lens-based or a critical massing of materials and technology and a collage of sorts of everything. Structures of power can also be invisible and can be larger than the eye can see. Artists like Sanaz and myself see these and make them visible and push at them from different sides so we can all see and push back. Sanaz is a rare artist who can synthesize her deep feelings about her childhood during the war between Iran and Iraq, being an immigrant like my family after the Second World War. The thing that is also very engaging about Sanaz is she is a sincere and kind person even after all the trauma. When I listened to her audio/film pieces I felt like I was exactly where they were originally filmed, the kaleidoscope she created was as real as any photojournalism I have seen or heard, which to me says there is little difference in the experientiality of the intention and effect of the work.

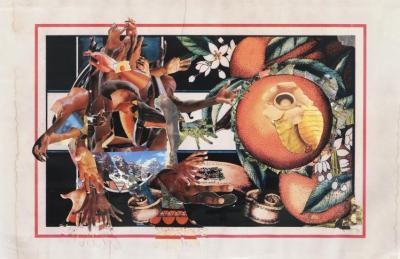

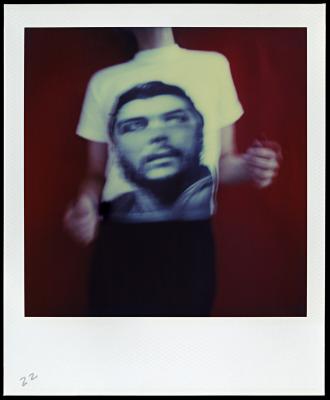

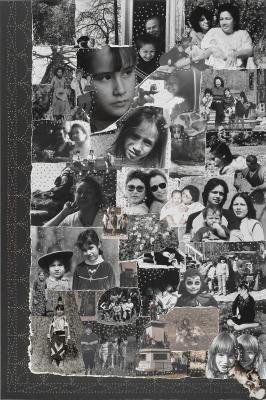

Sanaz Mazinani, Tokyo/Damascus, 2012. Pigment print, mounted and laminated to Dibond. Overall: 149.9 cm. Purchase, with funds from the Canada Now Photography Acquisition Initiative, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas Metivier, 2021. © Sanaz Mazinani. Courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery. 2021/101.

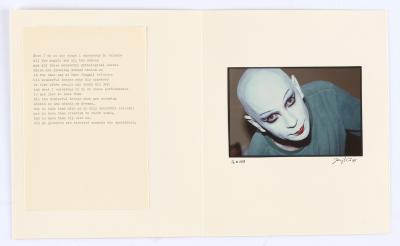

Foyer: The patterns and composition of the works in your Conference of the Birds series have been constructed with such intricate detail. Can you briefly walk us through your creation process for these works?

Mazinani: Yes, the process is rather labour-intensive. I begin with reading articles and looking for image documentation of these movements. Through this process, I have amassed a large archive of images and from there I look for image pairings that I could come together in interesting ways. I consider the subject matter, but also aesthetic choices such as colour, composition, and depth of field in the images that I choose. From there on the process of making the final montage is done in Adobe Photoshop software. I pair, copy, paste, and crop endlessly until I start to develop a pattern that I like. I often make the pattern much larger and then select the final tondo from a larger rectangular artwork.

Foyer: In this series, you’ve created an interconnectivity between the Occupy movement and the Arab Spring. Do you think most people see the two as aligned/similar? In your opinion, what role can artists play to help bridge the gap between global activism movements?

Mazinani: The Conference of the Birds series brings together popular images of the Occupy Movement with those of the Arab Spring. By placing images of these two distinct movements next to one another and digitally combining them into patterns that entwine, I wanted to bring the people in these movements together. For me, these patterned works become a symbol for the interconnectivity of universal struggles. With this work, my aim is to use the semiotics of pattern to reflect upon the possibilities of coexistence in a globalized world.

Foyer: What do you find moving about Louie Palu’s work? What are the main similarities you perceive between his practice and yours?

Mazinani: What I find incredibly moving and important about Louie’s work, is his dedication to presenting truth through the photographic image. His depth of research and commitment to his subject matter offers viewers a chance to dive into the issue and get closer to understanding the reality. What I find similar between our works is our ability to identify and present (although in very different ways) the beauty of humanity.

We Are Story: The Canada Now Photography Acquisition is on view now on Level 1 (gallery 128) of the AGO, until July 23, 2023.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)