What it means to be seen (again)

Prince Robinson tells the story behind an old 50-plus-year-old Polaroid and its journey to the AGO.

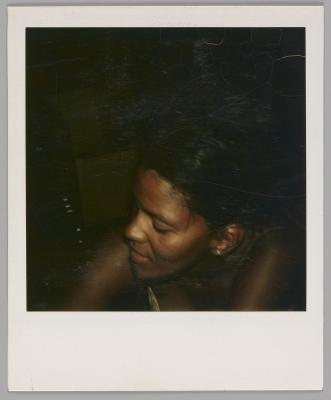

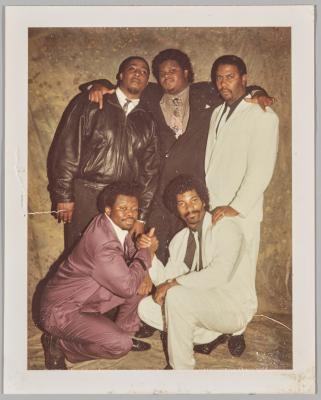

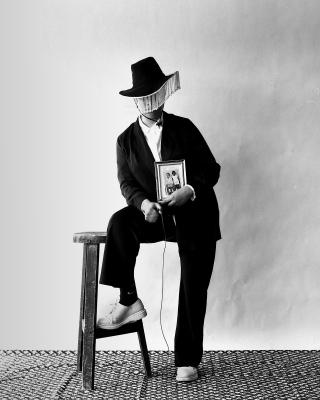

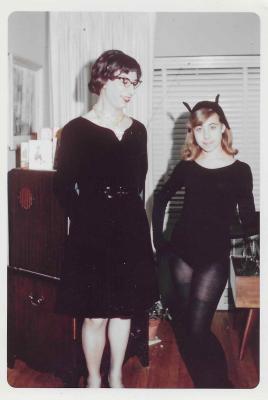

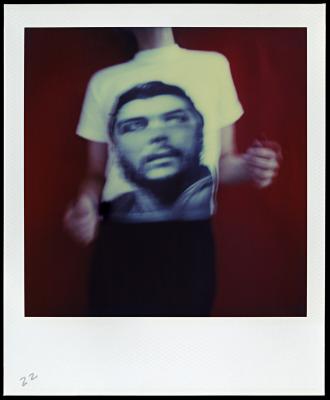

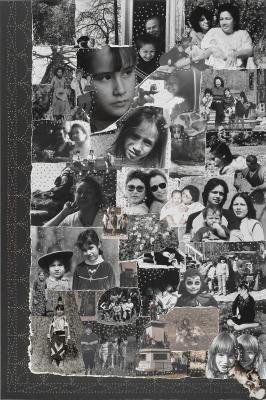

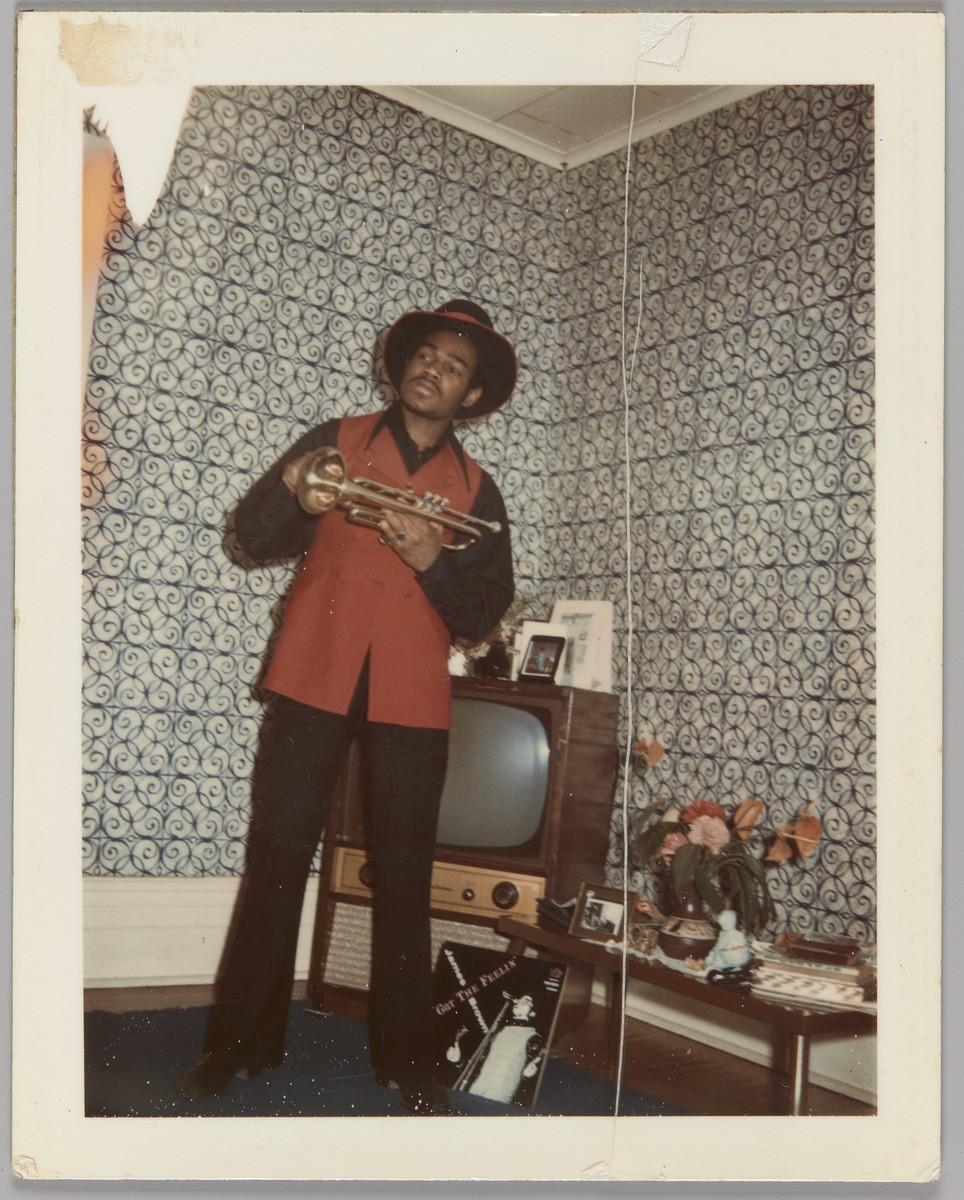

Angella Robinson, Prince Robinson, 1963-1970. Colour instant print [Polaroid Type 108], Overall: 10.8 x 8.5 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018.

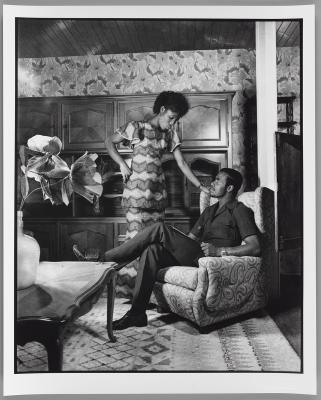

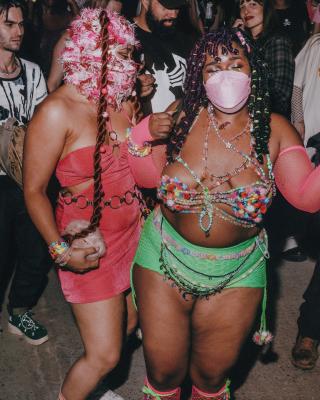

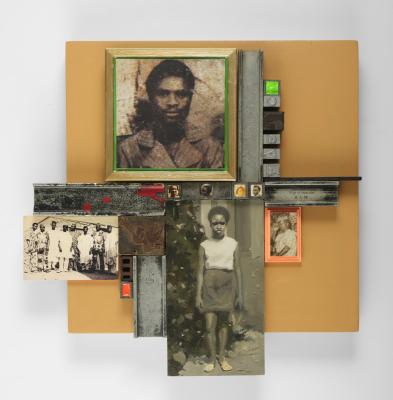

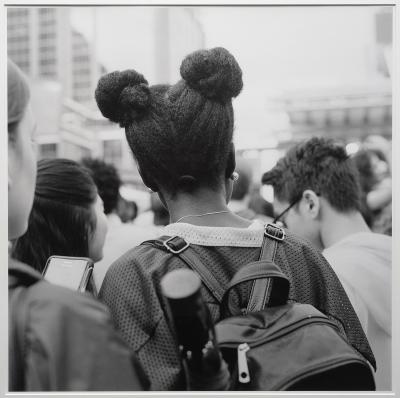

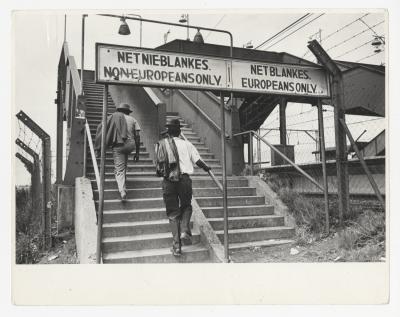

Not much is known about the more than 500 photographs featured as part of the What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life exhibition. Lost, discarded or abandoned, these photographs come to the AGO from the collection of Toronto artist, educator and co-curator Zun Lee, who spent more than six years gathering them from resellers across the United States.

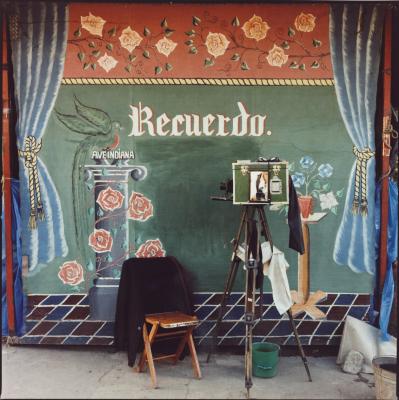

But now, thanks to a chance visit to the Gallery, we know more about one. Jeanette Robinson-Daley spotted a familiar face on the walls of What Matters Most when she visited the AGO on an afternoon in late August 2022, minutes before the Gallery closed for the day. It was her father, Prince Robinson; a young Black man dressed to impress, trumpet in hand, unmistakably 1970s wallpaper in the background. A copy of James Brown’s 1968 album I Got the Feelin’ placed by his feet.

As it turns out, this photograph was taken in Toronto’s Christie Pits neighbourhood in the early 1970s by Angella Robinson, Jeanette Robinson-Daley’s mother, although the details of how it ended up in California – and eventually on eBay, where Zun Lee spotted it, remains unclear. What’s more, Prince was an amateur photographer in his own right. At the time of this Polaroid’s creation, he was making ends meet by snapping and selling photos of clubgoers across Toronto for $2 a pop.

We sat down with Prince to find out how it feels to journey back in time through this photograph now miraculously on view at the AGO. He recalled his life as a young man; emigrating from Jamaica, landing first in bustling New York City and settling in Toronto. Decades on, his memories are as vivid as ever.

From Jamaica to a new world

“Originally, I came out of New York City and then I came up here [Toronto]. My sister had migrated from Jamaica and she was in Toronto. She just had a baby. At the time, I was going to school at the YDA [Youth Development Association] in Harlem on 125th Street, right beside the Apollo. And I decided to come up to visit her. I didn't have any family down in the U.S. I was travelling on my own as a youngster.

It's funny when I look back at my age when I was doing that, without having someone to invite me up or sponsor me up [from Jamaica]. It didn't happen like that for me. I was a Sea Scout, so I had travelling expenses. When I was about 13 years old, I left [Jamaica]. My mom and dad allowed that to happen because I was involved with this organization. And it was a great idea too because it helped us as young boys to have direction. So when this Sea Scout group was presented to us, I was anxious to join, but I had to get permission from my parents. That's how the structure was. I told my mom, and she said, ‘Tell your father’, I told my father, and my father said, ‘Who's the guy who's gonna run it? Let me see. Let me meet him.’ It was like that. This was 1962, so way back. My father met the man and gave the go-ahead. I got involved and I grew in it. We started travelling when I was about 13 years old. By the time I hit 16 or 17, I'm in the Cayman Islands. And from there, I worked for a while doing refrigeration and air conditioning. I learned a trade and the next thing you know, I was in Miami. And then I headed up to New York City and that was it. New York was my home. A friend told me to go talk to these people lined up right in Harlem and they helped me to get a rooming house. The story just continues from there. I signed myself up for school on my own at the YDA. How many young fellas could say that?”

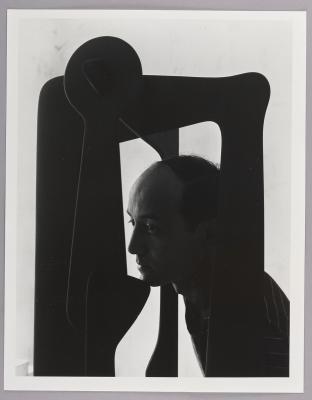

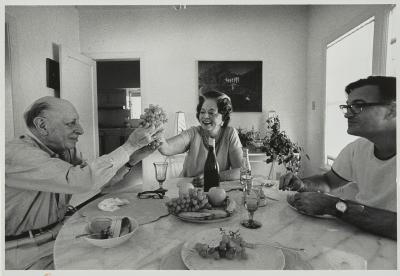

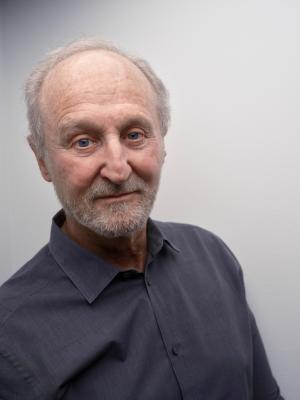

Prince Robinson. Photo © AGO.

New York vs. Toronto

“New York is a city that never sleeps. One, two o'clock, I'll be on the road, places would be open. You want food, you get it. More or less anything you want you can get it if you go further downtown, like 42nd Street, Broadway, that area. Harlem starts on 110th Street from Central Park on up to the concourse. Everybody's basically living the same way. People that don't have much. We refer to it as the ghetto, right? Slum lords don't want to take care of the building. You pay your rent, and they still don't take care of the pipes. Coming from Jamaica, I'm not used to that. Because we had a house, you know? We had a family structure, we went to church every Sunday, that kind of thing. I came out of that background.

The war in Vietnam was happening. I'm talking way back in 1965, ‘64, ‘63, ‘70. They gave amnesty in ‘74 but a lot of Americans were coming into Canada, lots of young fellows. If you're not going to college, you're eligible for the draft. So a lot of us, and I mean, a lot of us [Black men] wound up getting drafted and sent to Vietnam. A lot of them died. I have friends, good friends from the islands that never made it back. I came to Toronto to look for my sister. Toronto didn't look anything like New York. New York is a jungle with concrete buildings everywhere. You can stand at any point on the street and look straight down you’ll see a corridor in the sky. Stand on Seventh Avenue. Stand on Fifth Avenue. Look straight down until it narrows out. Coming to Toronto and you’ll see a building over here and a building there. It's grown up compared to how it was when I was coming onto the Greyhound bus across the border.”

Planting roots

“After a while, I met other Jamaicans and Caribbean people. There was one young fellow who was a friend of mine. He heard I was here, and he searched me up and found me. He might have been in New York, too actually. He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ The plan was to bring my wife, my now ex-wife here from Jamaica because it's a British Commonwealth. It was much harder to bring her to the States. And I settled in Toronto and started making it home. And [my ex-wife Angella Robinson] she's the one that took the picture, actually. And we started a home and got married in the process. That picture was taken before my daughter was born.

Setting the scene in the photograph

“I’ve always had a lot of clothes because in New York, you shop, you know? You get the deals and stuff. I'm always dressing up. Especially when you play in a band or you sing. I'm a singer too. You always have to look presentable. Because if you have something to present, you’ve got to look presentable. That’s one of the things that I roll with up until today.

I think it was a weekend. I was practicing because I had just bought that trumpet. I didn't bring the trumpet from New York. I bought the trumpet from a pawnshop. A pawnshop on Church Street. I’ve been into music since when I was a kid, right? So I bought it and started practicing. A friend of mine from England came here and was showing me how to do the scales and everything. Somebody stole it so I didn't get a chance to really fulfill that dream. Somebody came and borrowed it. And I was courteous enough to say, ‘Go ahead’. He came for Caribana, he was a Trinidadian guy. And I liked his spirit and he said, ‘Yeah, just I don't have a horn though’. He took it and I've never seen it again. That was that. But, yeah, during that time, it was a great time. We didn't have much. I just had my family–my wife and a baby on the way. We got married right at city hall.”

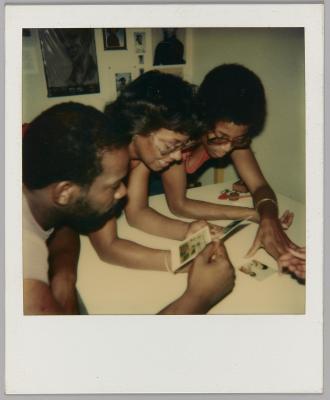

Picking up a camera

“In New York, when you dress nice and you go to the club, there's always somebody outside that's not even going into the club, he's doing a hustle. Now, there was this club called the Palms Café. It's right on 125th Street right by the Apollo, just down the street. My school was upstairs. I got to see all the artists coming in and out of the limousines like The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, you name it, you see them. At that particular place, there was a photographer who was hanging out and he’d take your picture. He asked you, ‘You want to capture the moment? You want to capture that?’ That’s where I got the idea from. When I came to Toronto, you were not supposed to work because of the immigration status thing. You don’t know how to make money. That camera made me some money. Who would have known that? You don't understand it, you just go along with it. Mind you, I'm about 20 years old, 21 somewhere around there, thinking how do I make some money? Honest Ed's! They sell the cartridge and they sell it at the cheapest price. I think was $7, or $8, I don't remember. I charged $2 a pop when I took the pictures and man, I made some change [money] from the clubs. I would be outside of clubs like the Brown Derby, Mrs. Nights, and a bunch of Black clubs because they play the music and you know, people dress up. I went around and took a lot of pictures, a lot of clubs from the east to the west. These Eyes was another club off Pape Avenue.

You know the song that says, ‘Shake it, shake it, shake it like a Polaroid picture’? André 3000? I can relate to that because you let you gotta let it dry. It develops right before your eyes. Great idea. I would walk with a few cartridges. Once the clubs slowed down at around one o'clock, I’d go to a basement party. More pictures! So I ate some food [earned a lot of money]. I was able to pay rent which at the time was $25 a week or something like that.

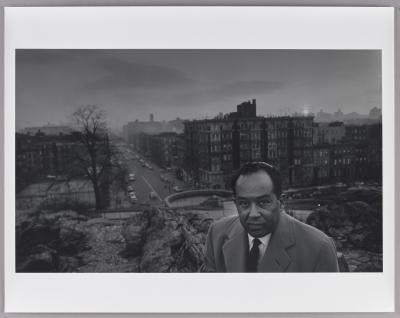

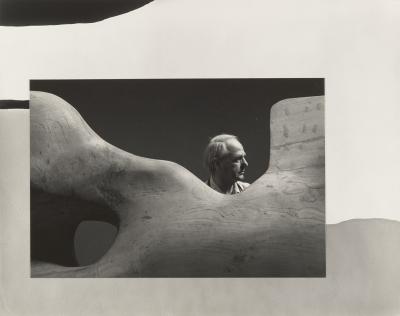

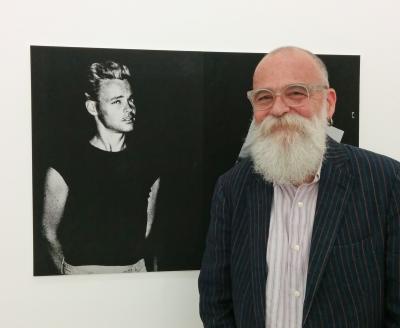

Prince Robinson with the camera he used in the 1970s. Photo © AGO.

When I was in the club scene, I sang in a band too. I had a band called Shockwave. I played at the Brown Derby. I played all over the place. And it takes a lot out of you, playing all over the city. I had a horn section with some white guys and a rhythm section with some Black guys. One of them just passed away. We made some money, not a lot though because we had too many members. We’re just trying to make it happen. You got to have something in you to do that because you're not making any money. What are you doing it for? You're not getting famous yet. It's like a, it's a journey, a long journey, but the hope is there. I wrote songs. One of the guys who signed me wanted to give one of the songs I wrote to Harold Melvin. Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes.

I think it just faded out. Because I eventually got my papers and started working properly. A friend of mine from Jamaica introduced me to the autobody shop. They wanted somebody to just clean up after the workers. I took it to it: sweeping the shop and cleaning the windows. I think it was a little more than $1.50 an hour at the time. I was just learning the trade by observing, soaking it up like a sponge. I wasn't there long though. I was there for like six weeks and I saw enough to go to another autobody shop and say I can do this.”

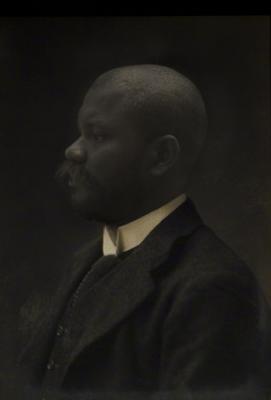

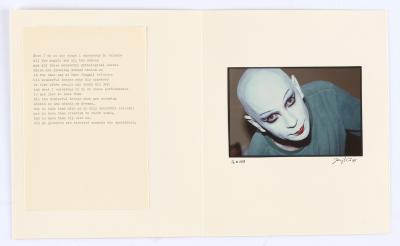

Prince Robinson seated with his daughter Jeanette Robinson-Daley. Photo © AGO.

On view at the AGO

“This freaked me out. Because when [Jeanette] said ‘Dad, I saw your picture at the Art Gallery of Ontario!’ I said, ‘Come on!’ It's crazy. I'm saying to Jeanette, ‘What are the chances? What are the chances?’ I took this picture back in 1972, 1971. It was a long time ago! We're in 2022! And any of the pictures with a skinny border from Toronto? I might be responsible for it. I took a lot of photos. People knew me. But some of those guys are my age or older than I am. I don't know if they're still around, who passed away or what. People just disappeared in the cracks after a while. But thank God, I'm still here and still keeping up because I changed my lifestyle. I started going to church and really changed.

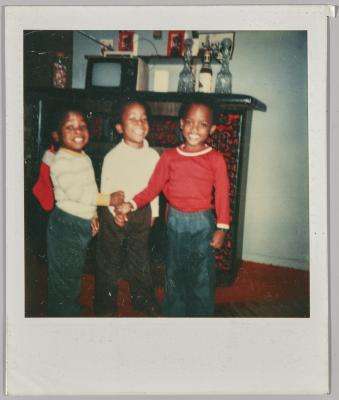

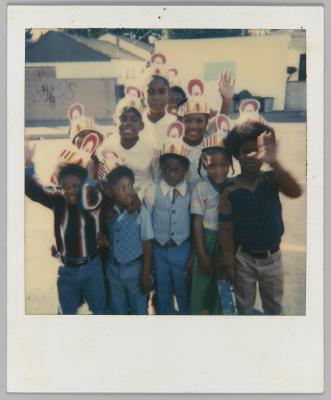

Families were migrating here at that time, a lot of them. I took some pictures and they’d send them home. That was a big thing for them. Because say, a woman would come up to Canada and leave her boyfriend or her fiancé or husband back home. And I'd be called in because I was the guy who can straight away take a photo. I did a lot of those too. It’s now 30, 40 years ago, who knows, but I was a big part of that. We go to Centre Island on a weekend. And here's Prince with a camera with a couple of cartridges, taking pictures. They would invite me to the house too. They want pictures of them sitting in their living room. Like “I'm living a little better now. I'm in Canada. I'm living better now than before”. Click, click, click and, before you know it, you put it in an envelope and mail it.

It faded after a while because I was working and I was making real money. But it helped. I'm not going to knock it. It made a difference because you have to have some form of income. By 1974, I was good to go.”

The Robinson family has chosen for the photograph of Prince to remain in the AGO Collection.

If you were in Toronto in the early 1970s, and think you have a Polaroid made by Prince Robinson, we’d like to hear from you. Email us at [email protected].

What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life was on view at the AGO until January 8, 2023. The exhibition is co-curated by Zun Lee and Sophie Hackett, AGO Curator, Photography. Pick up the exhibition publication from shopAGO.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)