New Frontiers of Printmaking With Naoko Matsubara

The acclaimed printmaker reflects on her 70-year career and new AGO exhibition

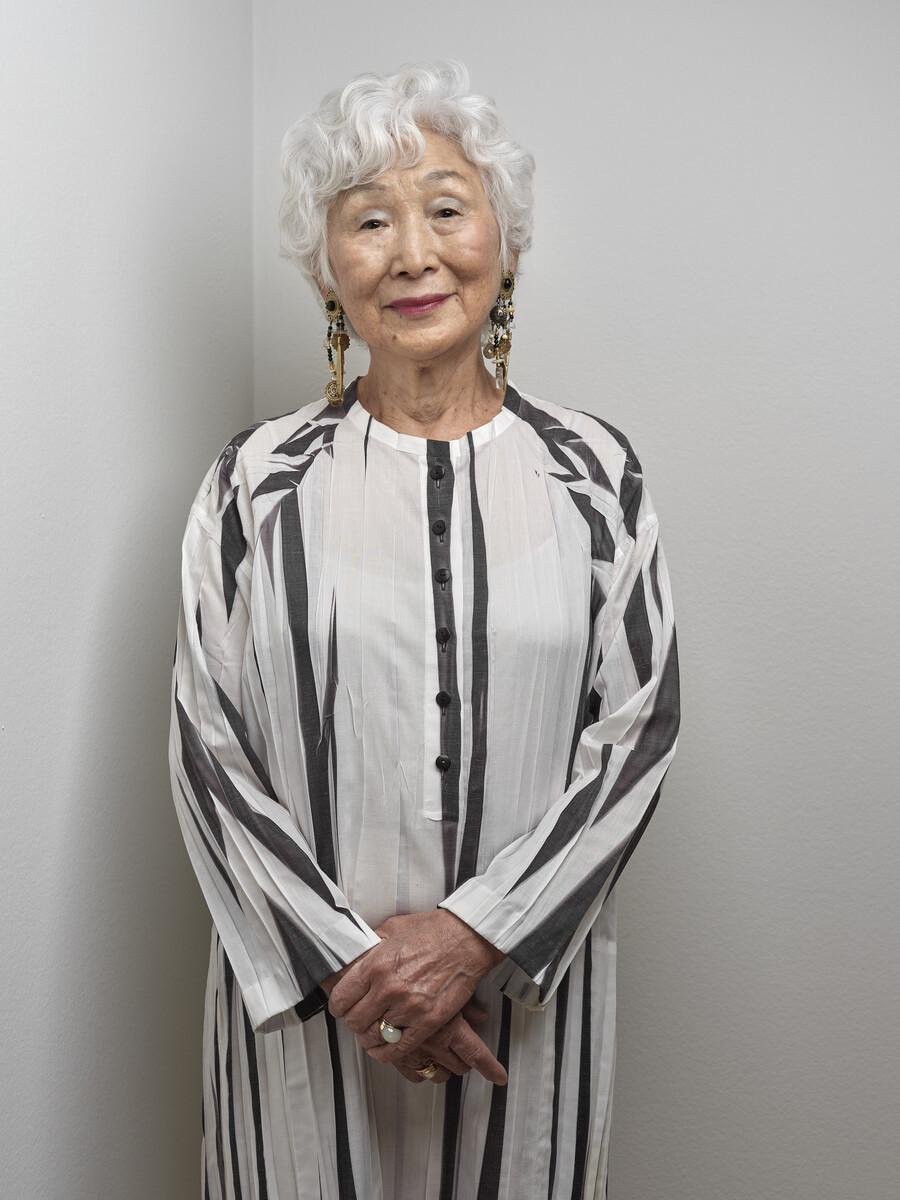

Naoko Matsubara, 2025. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

“I aim to continue to find ways – through woodcut printmaking – to innovate.”

For Naoko Matsubara, it is crucial that her work be associated with the broader canon of modern art rather than pigeonholed as traditional Japanese printmaking. The multi-disciplinary artist has led a 70-year career and continues to be driven by a passion for breaking new ground. Her renowned woodcut prints speak through a joyful language of colour, exploring personal and art historical subjects.

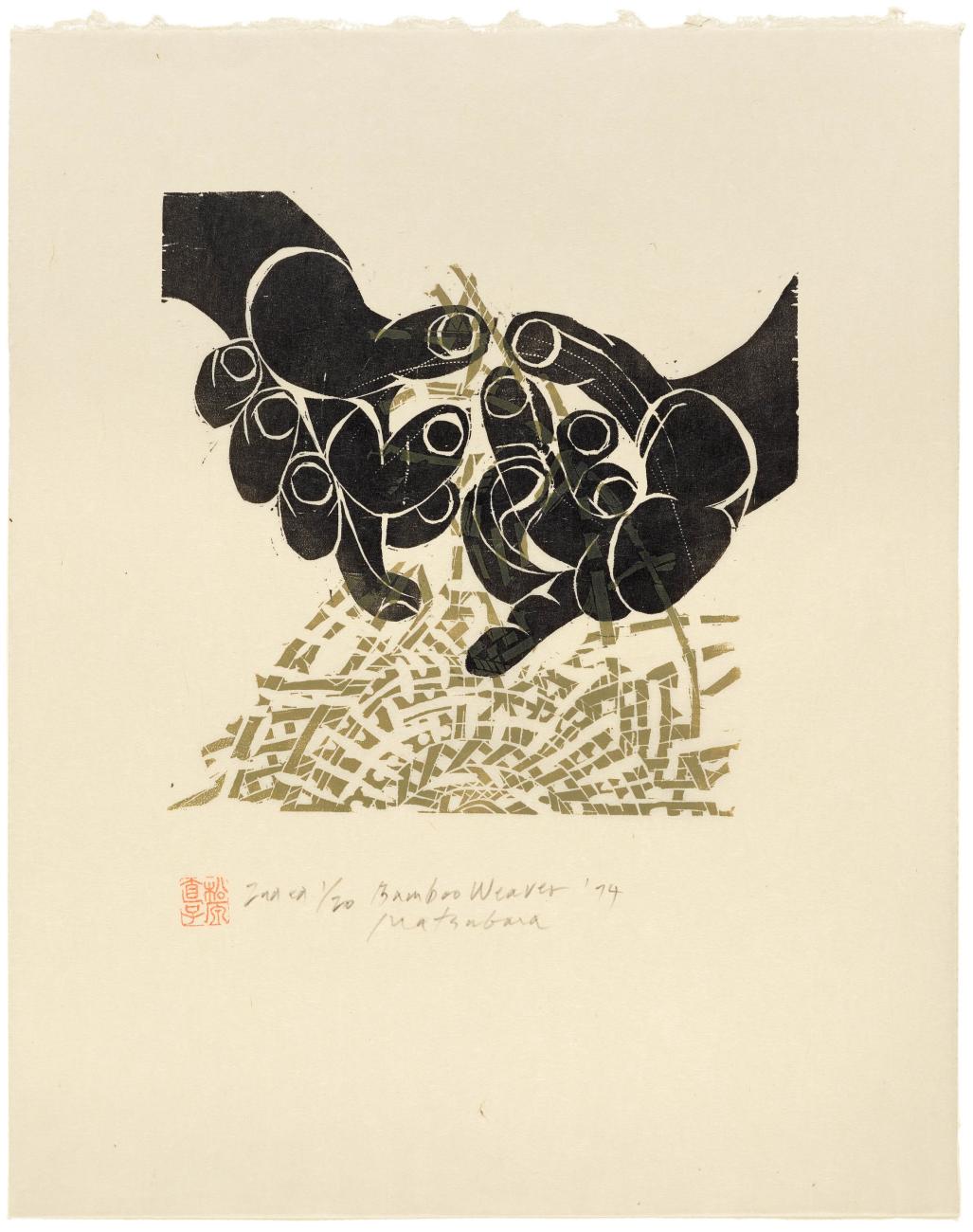

On view now, Naoko Matsubara is a career-spanning presentation of 20 woodcut prints by one of Canada’s leading printmakers. Curated by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art, this marks Matsubara's first exhibition at the AGO. Eight prints are from the acclaimed series In Praise of Hands (1973 – 2020). Inspired by Matsubara’s observations of her infant son’s hands in the early 1970s, the series has evolved into a decades-long homage to the complex work of human hands. Another highlight is Tagasode (2014), a two-meter, single-sheet print recalling an ikō–the traditional piece of furniture on which a kimono hangs. Finally, the show is complemented by a short film featuring Matsubara at her beautiful home studio in Oakville, Ontario.

Matsubara spoke to Foyer on the day of the exhibition’s opening. In a flowing white dress with a fragmented stripe design slightly reminiscent of her work, she reflected on her love of woodcut printmaking, her 70-year career, and her endless pursuit of artistic evolution.

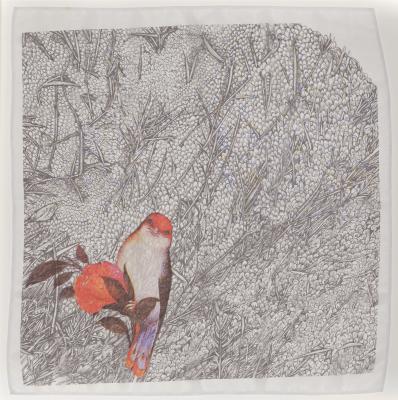

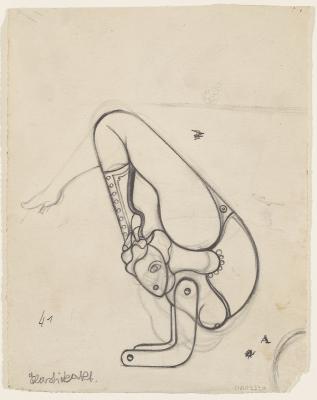

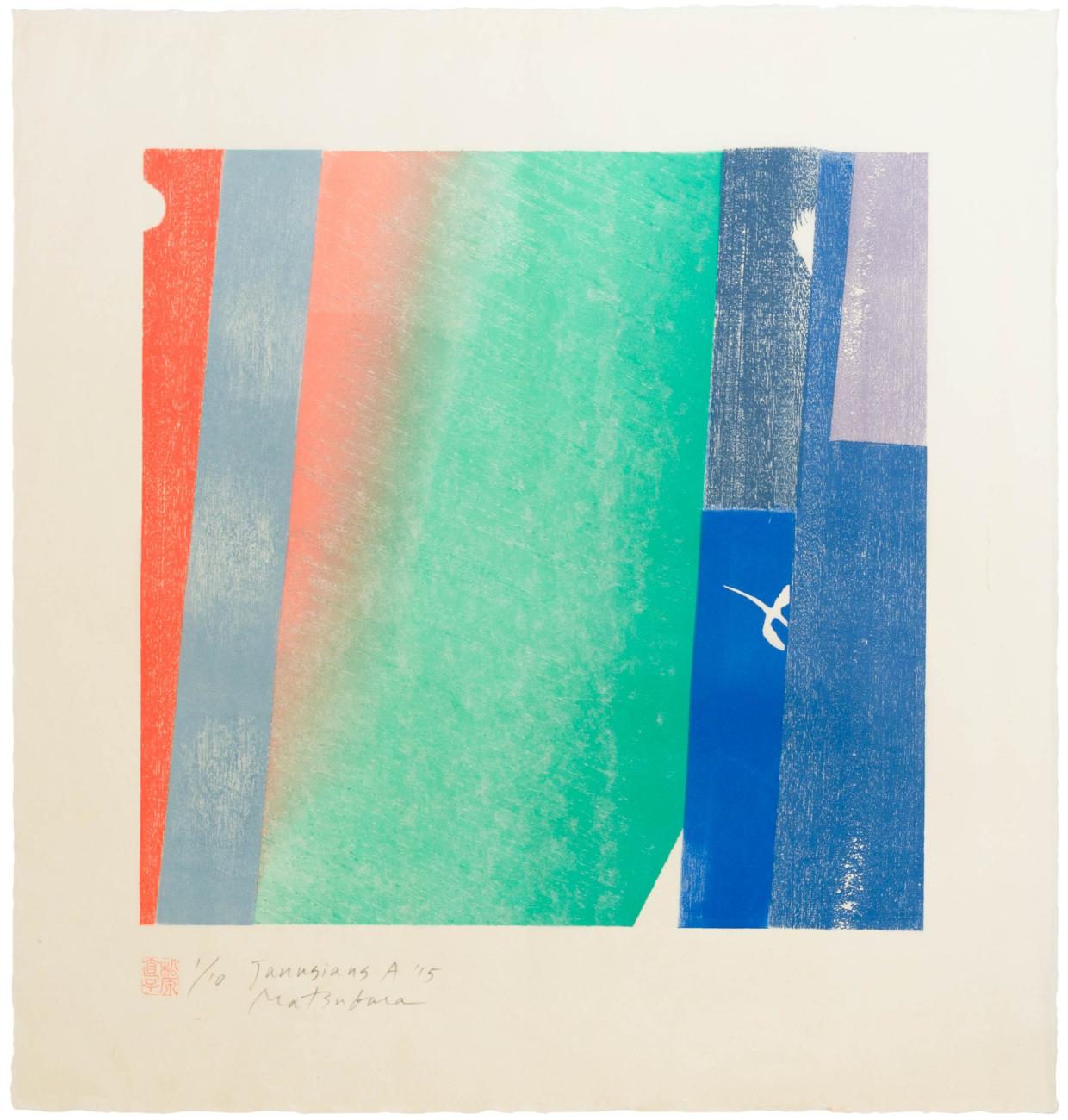

Naoko Matsubara. Janusian A, 2015. Colour woodcut print on handmade Japanese paper, Sheet: 68.5 x 65 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of the artist, 2024. © Naoko Matsubara. Image courtesy of the artist. Photo: Yoshiki Waterhouse

Foyer: When did you first fall in love with woodcut printmaking? What first inspired you to pursue the art form?

Matsubara: You don't have to have a good education to become a good artist, but I happened to have had one. I am very grateful to the many mentors I've had over the years. They all influenced me immensely. People think that because I am Japanese, my art is just traditionally Japanese. Woodcut printmaking (ukiyo-e) has been a tradition in Japan for centuries, and people want to connect my work with that tradition, but frankly, German Expressionism is what I most closely align with because of my education.

There are thousands of years of Japanese art history, dating back long before the creation of ukiyo-e in the mid 18th century. Japanese Emakimono artists from the Heian period [794 - 1195 CE], sculptors from the middle ages, painters from the 16th and 17th century, and a variety of Japanese architecture have all inspired me immensely. These works have informed my artmaking, but I have been outside of Japan since I turned 23 and I’m now 88. There is a part of me that is deeply rooted in the Japanese Shinto religion, which has existed as long as the nation itself. My father was a Shinto priest in Kyoto [Japan]. I grew up surrounded by beautiful trees and plant life. I was not a talkative child, but I was keenly aware of my environment. My mother was very fond of flowers, and she always had many different varieties, all of whose names I memorized. In this sense, I am firmly connected to my Japanese roots, but artistically I have always been more focused on the broader world of modern art especially in Europe and the United States. And I have been endlessly searching for ways to break new ground as an artist and do what has not yet been done.

How do you feel that search has been going?

I hope it’s going well. People imitate me, and that's all right – that's their business. I’ve cultivated many new directions for this medium, and it brings me great joy. I aim to continue to find ways – through woodcut printmaking – to innovate. It really is a lot of work; sometimes ideas don’t work out and you question your abilities. But when you are persistent, interestingly enough your best work doesn’t come from your brain. It comes from a source much larger than yourself, almost as if the work is given to you. That state of mind is not easy to obtain, but once in a while it comes, and it is truly exhilarating. What a wonderful feeling.

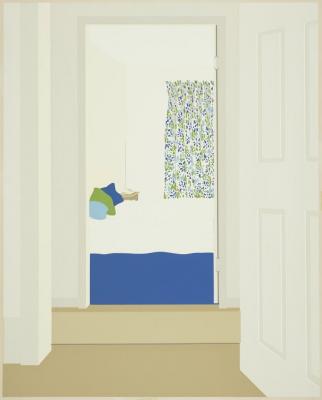

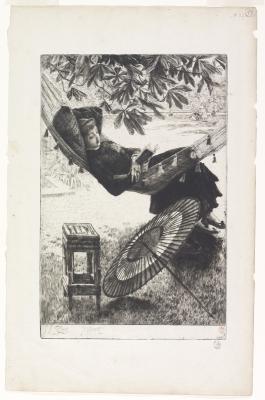

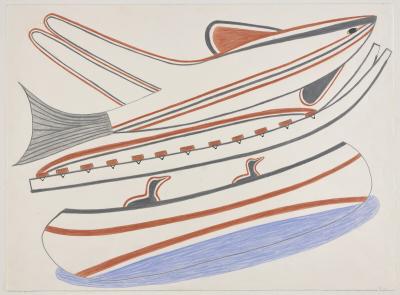

Naoko Matsubara. Joys of Spring, 2006. Colour woodcut print on handmade Japanese paper, Sheet: 63.5 x 98.3 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of the artist, 2024. © Naoko Matsubara. Image courtesy of the artist. Photo: Yoshiki Waterhouse

Can you share the inception story of your ongoing series In Praise of Hands?

When my son was an infant in 1973, I spent a lot of time observing his hands. When a baby is born, they are always clenching their hands. Then they start to ease up, and very slowly begin to pinch and poke. I started to notice the progression of my son's hand movements and began writing them down daily. He couldn’t even move his body yet, but his hands were saying so much. This is the first form of communication human beings are given. Little by little, I started to notice other people’s hands. We use our hands for such a vast number of reasons, both practical and expressive. That turned into one work after another for many years – I’ve done 30 of them. I can probably do 30 more because we do so much with our hands and they’re such a beautiful shape.

There’s such a diversity within the series. What has been your process for deciding which hands to depict and how to depict them?

Well, at the moment, I just watched your hands – you really moved them a lot. I did a print in 1994 called Conversation A. There are so many ways hands can talk. I learned how to practice Reiki, which is amazing. In Reiki, tremendous heat emits from the hands, making the hands healers. I’ve also observed people very busy in their work – pharmacists sorting medications, musicians playing their instruments – and it’s so fascinating. I apply my understanding of colour and design, and I just have fun with it.

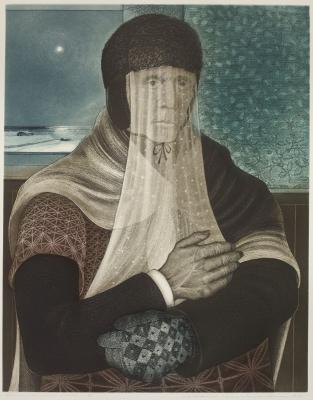

Naoko Matsubara. Bamboo Weaver, 1974. Colour woodcut print on handmade Japanese paper, Sheet: 56.5 x 46 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of the artist, 2024. © Naoko Matsubara. Image courtesy of the artist. Photo: Yoshiki Waterhouse

Can you talk about your work on Tagasode? How specifically were you inspired by the ikō?

[In Japanese, the word] “tagasode” means “who’s sleeve is it?”, and sleeve basically means kimono. When I started with that work, I was not thinking about tagasode at all, but I was just playing with colour and mass. It ended up being quite large. After I had almost finished, I looked at it, then I thought it looked like kimonos hanging on ikō . In Japan, I have seen so many paintings in the past that depict kimonos hanging – this style was considered a scene in the art world. And although I've seen many of them before, my tagasode was nothing like theirs, but it looked similar. That's why I named it this - not so much because I intentionally made it that way.

It often happens that I make something and then I have to find a title for it – which can be challenging. I used to discuss potential titles with my late husband. Now I do so with close friends sometimes. We talk for hours until [a title] comes. Sometimes I set out with a concept before I start working. Other times the concept forms itself and I become aware of it after. I think the latter is more interesting.

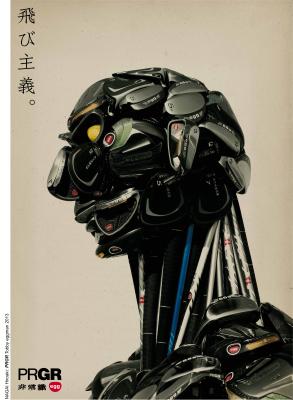

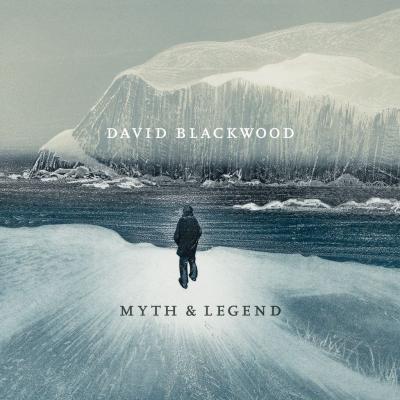

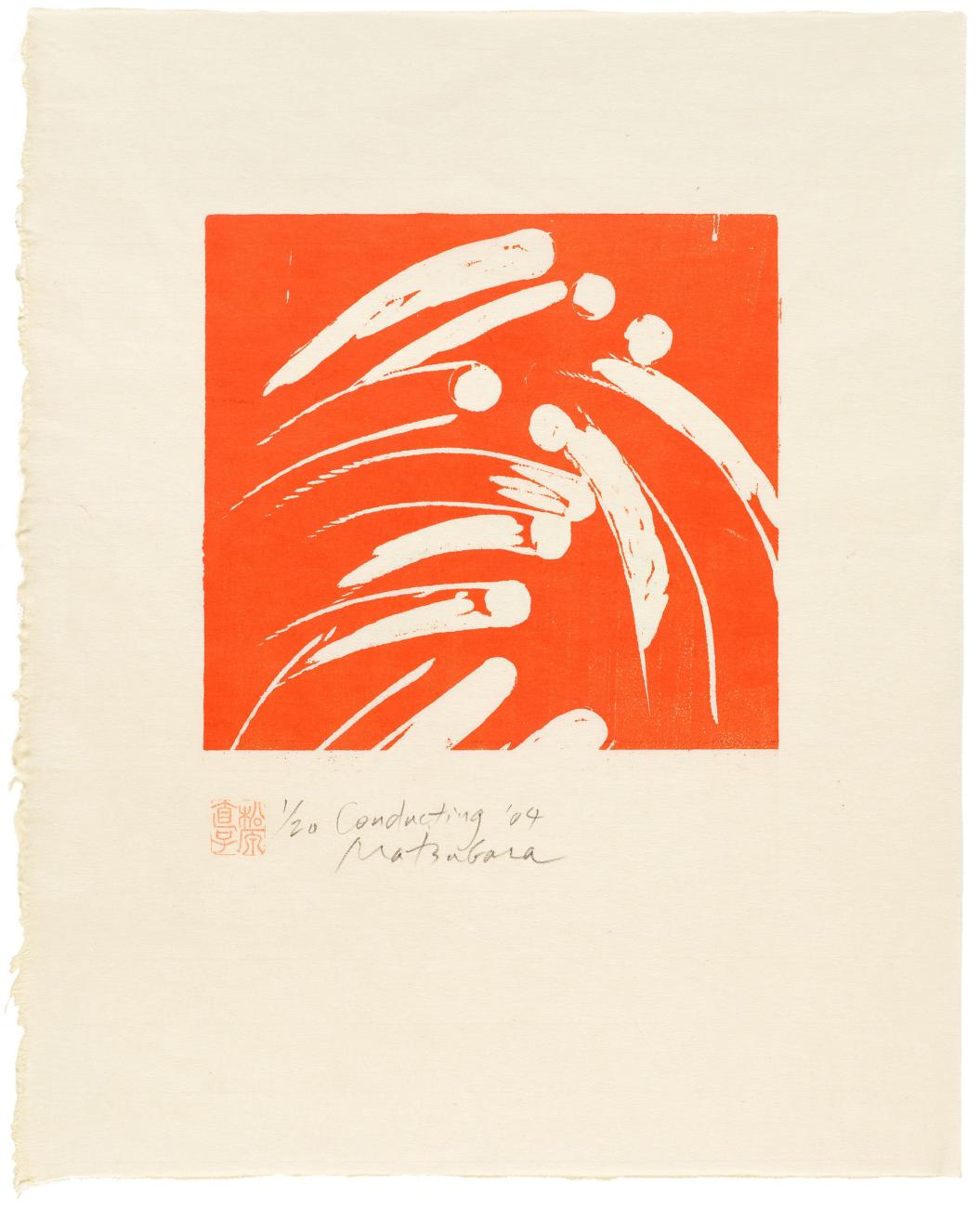

Naoko Matsubara, Conducting, 2004. Colour woodcut print on handmade Japanese paper, Sheet: 56 x 39.6 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of the artist, 2024. © Naoko Matsubara. Image courtesy of the artist. Photo: Yoshiki Waterhouse

You've led a monumental career, and you've exhibited works all around the world for decades. As you watch this career-spanning exhibition go on view, how have you been reflecting on your body of work in recent days?

I feel very lucky that my career is so well celebrated, and that people seem to like my work. Some people strongly like it. Many people don't understand it, but that's the way it is. I enjoy seeing this exhibition hung in a museum, I have been living in Oakville, Ontario for over 50 years solidly, and it is important Art Gallery exhibit my works and collects them.

There is a small number of people who truly understand what I'm trying to do, and that gives me joy. That happens all over the world. I have published 20 books of my woodcut works. I’ve had people from countries I have never visited write to me telling me how much they love my work. That is a wonderful feeling.

Naoko Matsubara is on view now in the Nicholas Fodor gallery (gallery 140 and gallery 141) on Level 1 of the AGO. The exhibition is curated by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art at the AGO.