Diasporic transitions with David A. Bailey and Alex Farquharson

The co-curators discuss the landmark exhibition Life Between Islands and reflect on its AGO opening

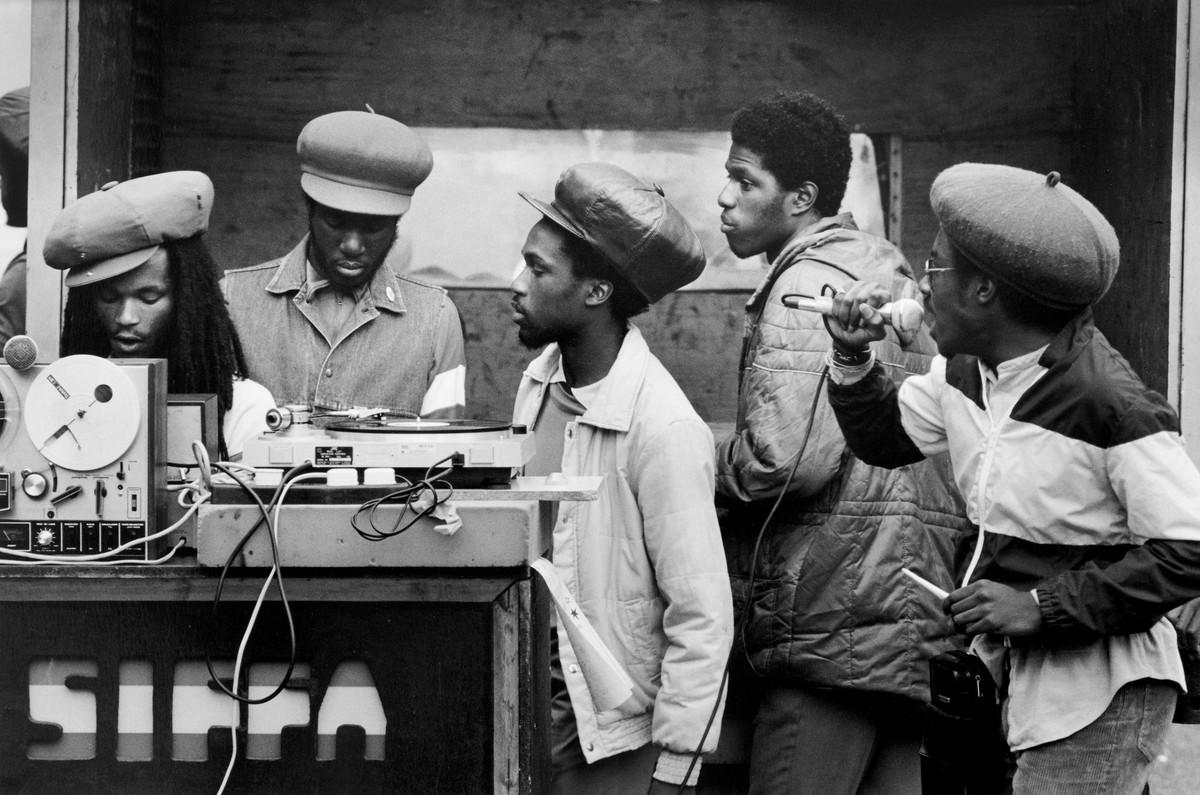

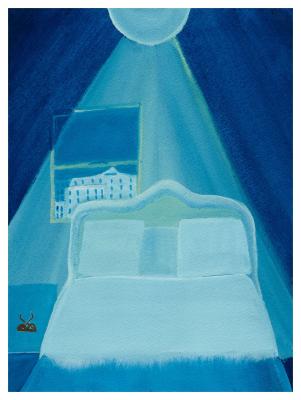

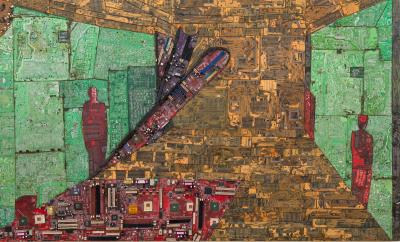

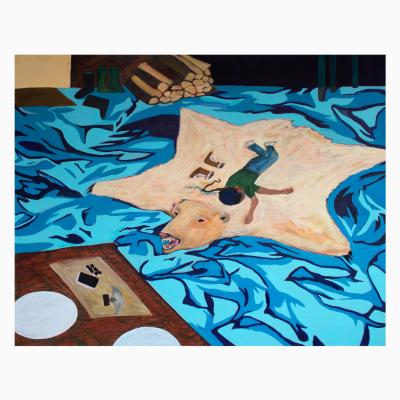

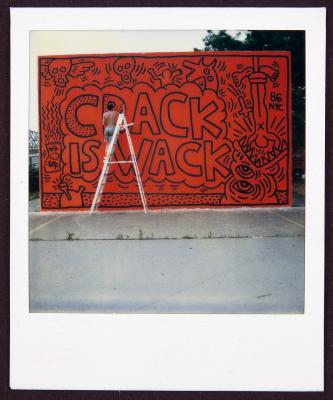

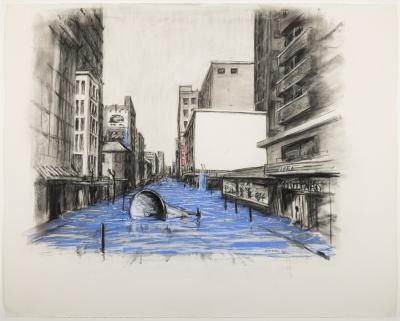

Denzil Forrester. Jah Shaka, 1983. Oil paint on canvas, Overall: 213.4 × 274.3 cm. Collection Shane Akeroyd, London. © Denzil Forrester, courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

When Alex Farquharson became director of Tate Britain in 2015, he already had the intention of putting together an exhibition showcasing the work of contemporary Caribbean artists in the UK. He knew that for the show to be authentically rooted in the Caribbean diasporic experience, he needed to approach the right collaborator – renowned British curator and photographer David A. Bailey was his first choice. As a curatorial team, the two conceived of the landmark exhibition Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s–Now, which came together over several years and opened at the Tate Britain in 2021. After a resounding success, the exhibition has traveled across the Atlantic, making its Canadian debut at the AGO.

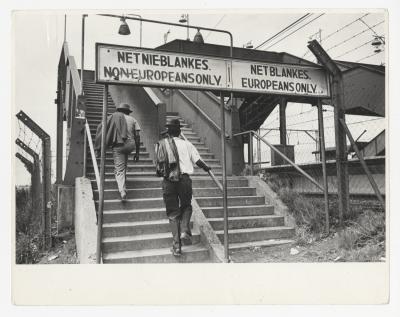

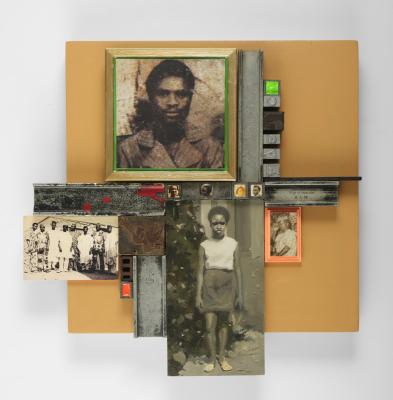

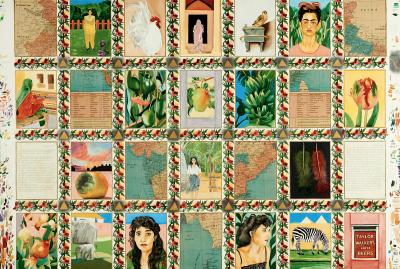

On view now through April 2024, Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s–Now examines the relationship between the Caribbean and Britain, reconsidering British art history in the 20th and 21st centuries from a Caribbean perspective. Featuring more than 30 artists, including Frank Bowling, Aubrey Williams, Sonia Boyce and Alberta Whittle, the show spans a range of mediums, from paintings to documentary photography, film, and sculpture. The show’s centerpiece – The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix by Michael McMillan – is a meticulously crafted, life-sized living room, fashioned in the style of a 1980’s Caribbean home. With the AGO presentation overseen by Julie Crooks, AGO Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora, Life Between Islands invites visitors to explore themes like decolonization, the meaning of home, reclaiming of ancestral traditions, the nature of Caribbean and diasporic identity, as well as racial discrimination and sociopolitical conflict.

As the exhibition opened at the AGO in early December, Farquharson and Bailey connected with Foyer, each offering heartfelt insights about the inception of Life Between Islands, the art and artists that it brings together, and its new home in Toronto.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Foyer: Can you share the inception story behind Life Between Islands? How was the idea for the exhibition originally formed? And how long did it take for a massive group show like this to be fully realized?

Farquharson: In 2015, when I was being interviewed for my role at Tate Britain, I thought, “What is an extraordinary contemporary art and art historic opportunity here, that has not been properly surfaced, and that could be best surfaced at Tate Britain?” In thinking about Tate Britain’s national remit [commitment to increase the public’s enjoyment and understanding of British Art], it is only relevant and inclusive if you think of it in cross-cultural terms. In terms of British art and British society, there are amazing diasporic cultural experiences, some of which have been very harsh, experienced in Britain – a global dimension.

I had previously co-curated a Nottingham Contemporary show on Haitian self-taught art, and from that I had grown to really understand, appreciate and become fascinated by the wider history of the Caribbean, in particular the creolized, cross-cultural elements; and how that in turn has been brought to Britain, or here in Canada, and changed British or Canadian culture. From the get-go joining Tate Britain in 2015, I thought this is really a show we need to do, and very quickly approached David A. Bailey.

This exhibition had to come from collaboration. David is someone who is deeply invested in these art histories, was an integral part of the 80s Black art movement in Britain, and is himself of Barbadian background. All of those factors were needed for us to be authentic in how we presented the way that art was telling wider stories. From that point, we began with a loose idea of the structure; it would be multigenerational – beginning in about the 50s going up to the present – and there would be multiple generations and thematics.

Foyer: Life Between Islands includes the work of over 40 artists and spans numerous artistic mediums. Are there one or two specific works that, in your opinion, best encapsulate or symbolize the spirit of the exhibition?

Bailey: My good friend – who I went to university with – Michael McMcMillan produced The Front Room, which is pretty much my favorite piece. I like the idea that you can have a show, which can have really expensive installation pieces and paintings, but alongside that has artistic elements within an interior space – basically front room furniture that you could pick up for a dollar. I love the idea that we can be that eclectic. Also, that space is about being a space within a space within a space, so it’s almost like its own little museum in that space.

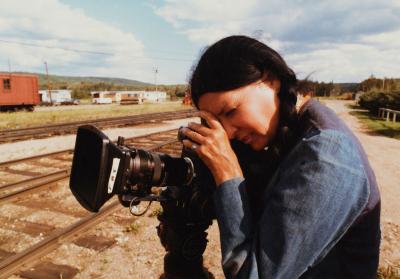

Isaac Julian’s work is phenomenal. I've worked and lived with Isaac and I've not met anybody who is as impassioned around the moving image, but also tries to push the boundaries around how that is presented. Isaac was a phenomenal filmmaker well before people like Steve McQueen and a whole range of others, but then decided to focus his attention on the installation environment, which he's completely transformed with the moving image. I understand what Julie [Crooks] has done [with her curatorial decisions concerning Julian’s work]. She has included three of his key works – one on a monitor, one that was shot in the 80s, and one that is a massive 21st century visualization – to show how he's how he's evolved within that work.

And of course, my partner in crime (my actual partner), Sonia Boyce who, like Isaac, has several pieces in the show. Some of her early more wall-based work, but also her complex moving image work around Crop Over and Carnival, which projects itself across different spaces: Barbados in the Caribbean, and the Harewood House in England. It illustrates the connection of the Harewood family in relationship to Barbados, making it one of the few pieces that directly travels between the two islands.

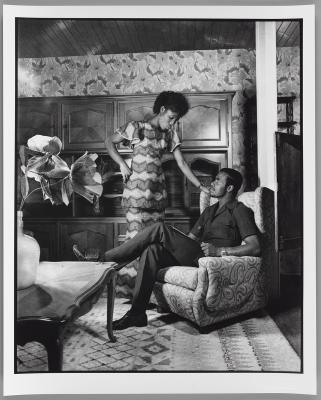

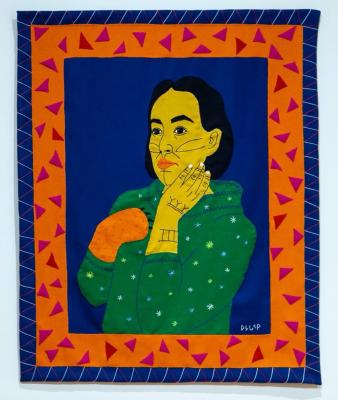

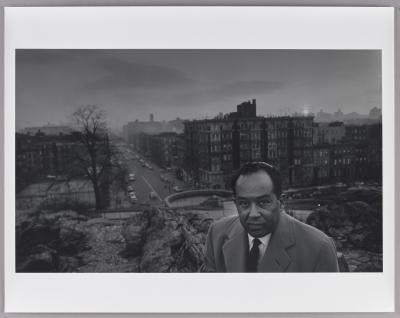

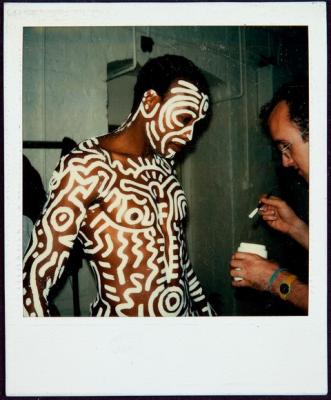

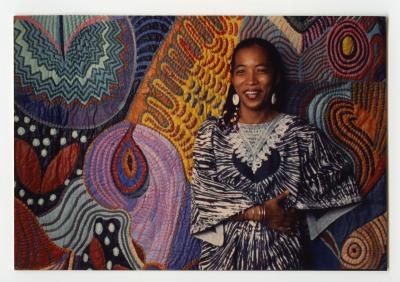

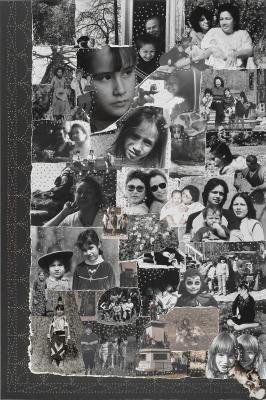

David A. Bailey, Co-curator, Life Between Islands, in The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix, 2023, by Michael McMillan. Mixed media site-specific installation © Michael McMillan. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

Farquharson: There's an early section of the exhibition featuring works by Ronald Moody, Aubrey Williams, Dennis Williams, Frank Bowling, and Althea McNish, among others. All of those have to be included in order to best represent the independence period; this road towards independence that has a cultural aspect and is anti-colonial, and that deals with ancestral roots. In the case of two Guyanese artists – Aubrey Williams and Dennis Williams – it deals with indigeneity and the culture of the First Peoples in Guyana.

For the 80s generation, Sonia Boyce is absolutely key. Her work in the show is very much in the diasporic space between the Caribbean and Britain, as well as the present moment in Britain and London. And likewise, Isaac Julian, who has a major presence in the show.

The documentary photographers like Vanley Burke are also crucial. They help anchor the artworks in other mediums. There are films and documentary moments in the show, where visitors can see through the lens, the events and struggles happening.

Towards the end, I'd say Hew Locke is an artist whose work is absolutely about what this show is “doing”. Then there's someone like Marcia Michael, whose work we're introducing for the first time in Canada. That piece about her mother at the end of her life, it’s so extraordinary and moving the way she gives her this digital and spiritual afterlife and works with her to envisage her memories of Jamaica.

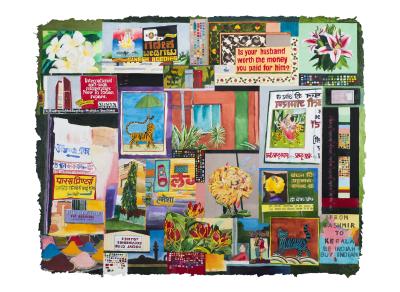

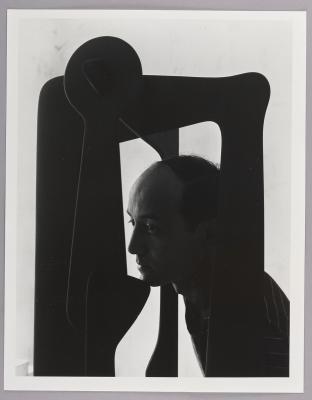

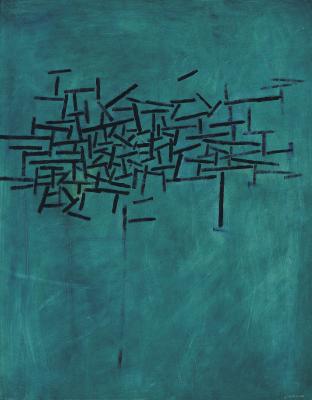

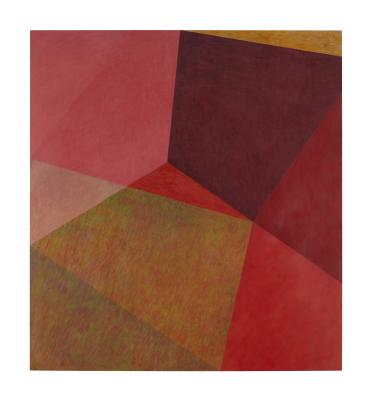

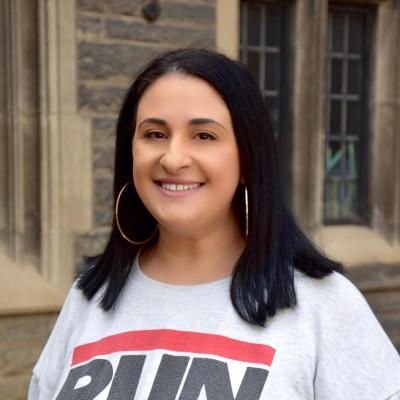

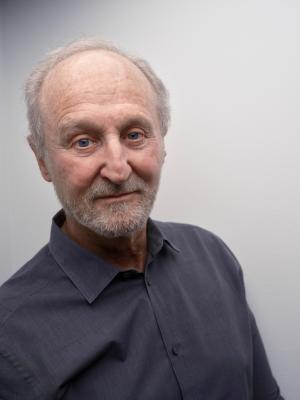

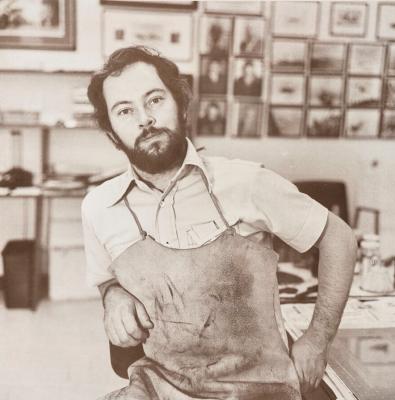

Alex Farquharson, Co-curator, Life Between Islands. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO. Artwork in background: Rachel Jones, a shorn root, 2022. © Rachel Jones

Foyer: Considering all the profound artwork inspired by or commenting on the Black experience in the Caribbean diaspora, in your opinion what is the role of cultural production in decolonization?

Bailey: I originated as an artist, specifically as a photographer, and I was mentored by the writer Stuart Hall. What I learned from Stuart, is the idea that cultural production is a strategic weapon. The whole basis of cultural studies, and the process of breaking up the cultural milieu, and making a strategic intervention within culture is done through this work that we do.

I was brought up in a generation of artists, within the Black art movement of the 80s, whose primary objective was to use culture or visual art etc. to make strategic political interventions. I was mentored by a generation of people who taught me to reread Fanon [and similar authors] and look at their ideas in terms of visual culture. It was about how you can use those texts as a way in which to talk about cultural appropriation [in relation to visual culture] and make strategic interventions. It's a generational thing, and I think if you were to talk to Sonia Boyce or Keith Piper – other artists of my generation - I’m sure they will say the same thing.

Additionally, I think there is a subsequent generation – people like Steve McQueen – who actually take it to a different mainstream level. To create mainstream work like 12 Years a Slave or Small Axe and still maintain an artistic practice is very difficult, and very important. For Steve, that’s the intervention.

Foyer: Julie Crooks has added several works to the Toronto iteration of Life Between Islands, including works by Rachel Jones, Alberta Whittle, as well as Michael McMillan’s Toronto-specific installation The Front Room. Can you share some of your thoughts about these new additions and what they add to the show?

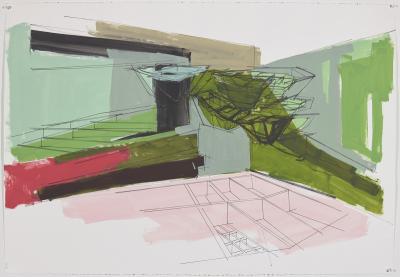

Farquharson: We worked closely on this show together, and some of that was out of necessity as this is a different space. The two big spaces here are larger than the ones we have at Tate Britain, so we needed to make the scale work. In a way, because we're not in Britain, we want to tell a tighter story that may flow more easily. It needed quite a lot of careful research. One artist that is entirely new to this iteration is Rachel Jones. I think Julie’s decision to add Rachel was right, because her work at the end of the show moves the focus back onto abstraction, similar to the Aubrey Williams works at the beginning of the show, but in a very new language. There’s still a sense of diaspora, with the language of forms and colours.

The most important shift, I would say, is Michael McMillan’s Toronto version of The Front Room. When we approached Michael to do The Front Room again, he agreed but he wanted to make this one a Toronto version, and in a slightly different era: the 80s. I think what this version of The Front Room does – even though the show is all about the British side of the Caribbean story – is that it helps Canadian visitors relate the show to their own family experience and plugs the whole show into the here and now.

Bailey: Michael McMillan’s room is exceptional. I think the way he's used archival imagery is really great. The television is obviously a piece of sculpture, but it is also an artwork, which is projecting images of Toronto back into that room. I think that works perfectly. It’s interesting because when you walk into that room it looks really simple, but in fact it is so complex. From the photographs, to the image of Christ, it is meticulously layered. So for me, that's the one that is “Toronto”.

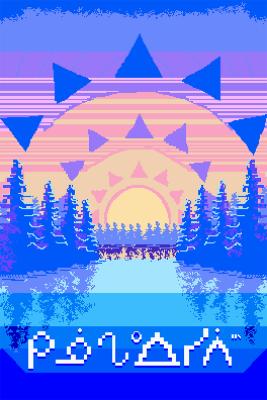

The new commission by Blue Curry is brilliant, because when we think about the Caribbean, we think about consumption, we think about tourism, we think about who's consuming all of that, and Blue’s piece talks to that experience. Anybody from Toronto who’s been to the Caribbean or has a notion of what the Caribbean means will understand that piece. Like The Front Room, it’s incredibly complex but speaks to a 21st century experience of the Caribbean, which I think most people from Toronto will grasp.

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s–Now is on view now until April 2024 on Level 5 of the AGO.