From friendship to foundation

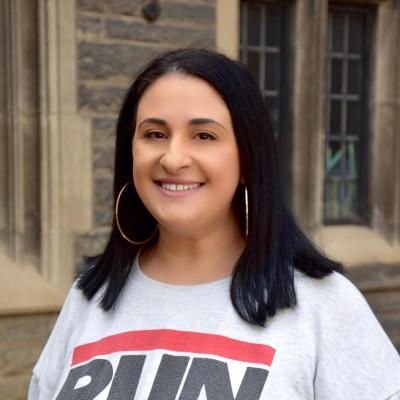

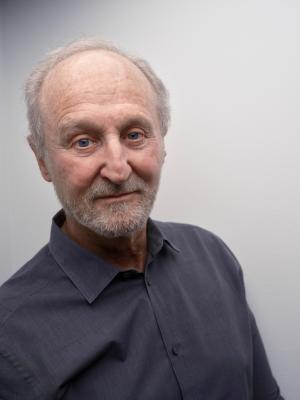

Gil Vazquez, Executive Director of the Keith Haring Foundation, discusses his friend Keith Haring

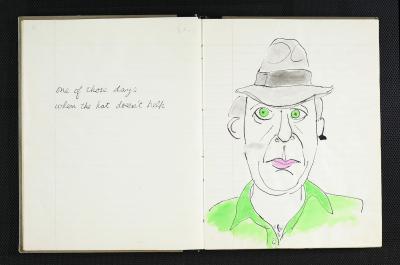

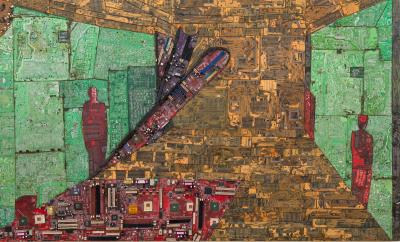

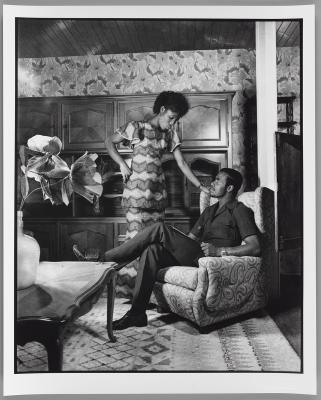

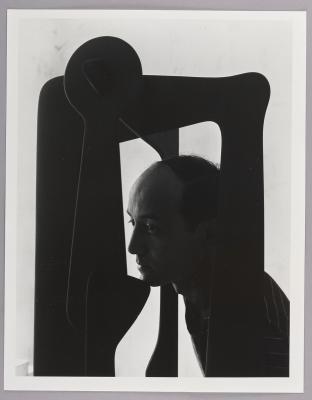

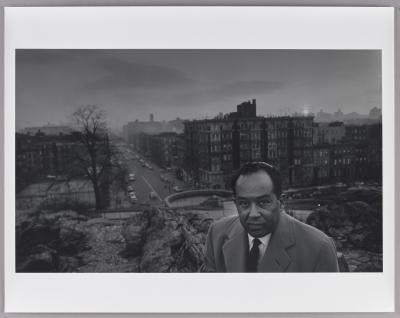

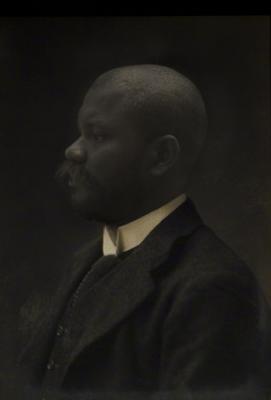

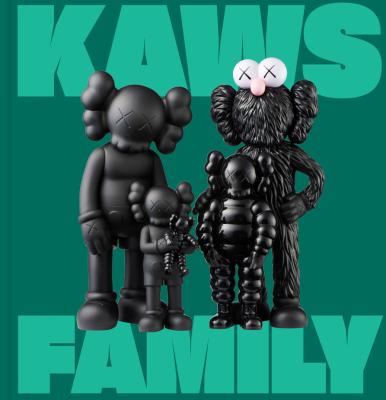

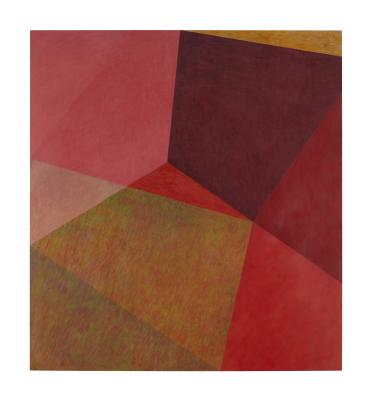

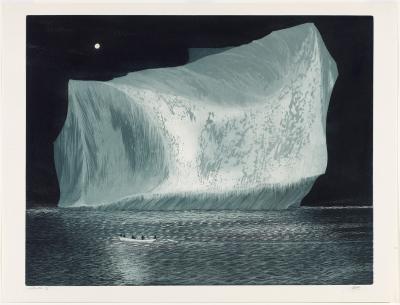

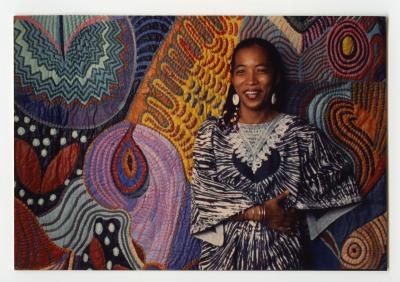

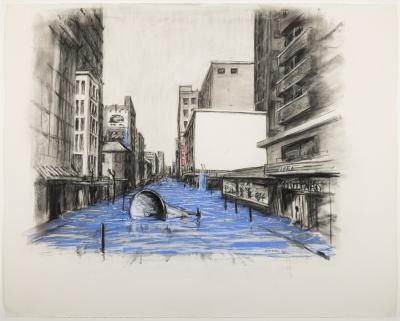

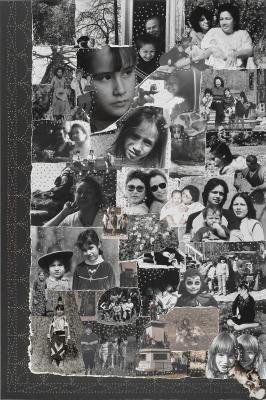

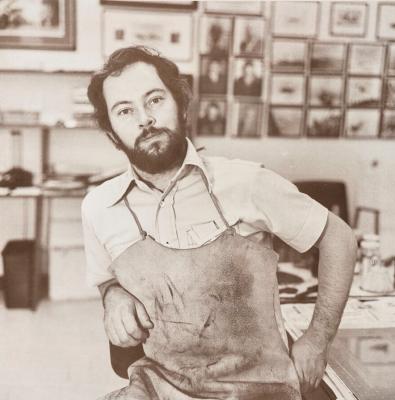

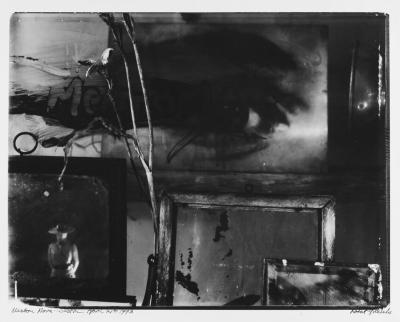

Gil Vazquez, Executive Director of the Keith Haring Foundation, with Keith Haring’s Red (1982 and 1984) © Keith Haring Foundation. Photo: Tracey Owusu ©AGO

Just shy of his 18th birthday, Gil Vazquez met Keith Haring for the first time. A born and bred New Yorker, he recognized him by sight. He knew Keith’s art – was familiar with his subway drawings, iconic imagery, and collaborations with RUN DMC. He was, he says, “an instant fan.” But nothing prepared him for the experience of stepping into his studio and really getting to know the man behind the art. Nor could anything that happened that day have led him to believe that thirty years later, he would lead the foundation that bore Keith’s name.

At the opening of Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody at the AGO, we caught up with Gil to hear from him what it was like to meet, know and work for Keith Haring.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Foyer: How and where did you meet Keith Haring for the first time?

Vazquez: I met Keith in May of 1988. I was a month and a half away from my 18th birthday. I was working at a store near Keith’s studio, a little t-shirt store. Keith walks in one day, looking for someone he knew. I’m immediately in awe. Turns out my co-worker and him are old friends. They had met at the Paradise Garage nightclub. My co-worker then asks me if I’d like to visit Keith’s studio and I was like, oh my God, of course.

Foyer: How aware of his work were you at this time?

Vazquez: I met him in 1988, at which point he was already super famous. He had done so much. I knew the subway drawings. I knew the baby. I knew the dog. I knew the Pop Shop. But I didn't know about his activism or who he was as a person. I'm a DJ by trade and was very aware that he had done an Adidas campaign with Run DMC. I was an instant fan. So, thanks to the guy at the t-shirt store, I walked into Keith’s studio. And, you know, it felt like I had landed on another planet, because I had no real context, no point of reference for what I was walking into. My New York City public school education hadn’t prepared me for this - maybe they had talked a little bit about Norman Rockwell and Picasso. But Keith Haring was someone alive and famous in his time. And young and active and so cool. Really, really cool. So, I walk into the studio, and he is there, hammering, tacks and nails into a wooden portrait of the Mona Lisa that he had bought on the street. In the studio, there were blank canvases, drawings, T-shirts, boxes, and people. It was an active space. He has a studio assistant, he has a studio manager upfront acting as gatekeeper, and I am just in awe, in complete awe. And he was super nice. I had all these questions. And I just started to learn about the man. We somehow became very fast friends.

Foyer: Tell me about being an 18-year-old DJ in 1988 in New York.

Vazquez: Important to understand that the scene was specific to downtown. I was born and raised in New York – I am a New Yorker - but coming from Uptown Harlem to downtown in 1988, as I did, was like entering another world. Downtown was magic, a world apart. It was the club scene, and music and art - this incredible confluence of culture. And Keith Haring was at the centre of it all in 1988 – he was the coolest guy, at all the coolest parties, knew all the DJs. He was a magnet, drawing people to him. The scene was very much about who you knew – invites only by word of mouth, no flyers, $5 at the door.

My brother was the one that introduced me to DJing when I was 10. He was born in the same year as Keith Haring. I did get to DJ once alongside Keith. He was painting a mural in Barcelona at a nightclub, and I DJ’d while that was happening, which was cool.

The club scene was college for me. And in a sense, it was almost church for Keith. I became a professional DJ shortly after Keith's passing.

Foyer: Who were the artists that Keith himself admired?

Vazquez: He really loved George Condo. I think he was Keith’s favourite painter. When I met Keith, his relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat was complicated, and they weren’t hanging out. Might have been the drugs, but there was always a kind of mutual respect. I suspect they each had something the other wanted – Jean-Michel aspired for Keith’s mass appeal, and Keith aspired for the critical acclaim. Especially in the early years, critics were not easy on Keith.

Foyer: In the exhibition, we see these incredibly intricate invitations crafted by him for his birthday. Why was that so important to him?

Vazquez: For Keith, birthdays were a celebration of life, a moment to celebrate his tribe and to bring together all the people he knew. He attracted just the best people - not necessarily the most famous, not movie stars, but just salt of the earth people. He wanted all these people in one place at one time, in the coolest venue, with the best DJs and the most exciting performances.

Foyer: What’s the tipping point in Keith’s career? What’s the thing that sent him from cool to internationally renowned?

Vazquez: He becomes instantly cool with the subway drawings – and from there on it is a consistent build. I attribute much of that to him not seeking notoriety for himself. The subway pictures are not signed – they are mysterious, they beg questions rather than answer them, they are generous. In an era of conspicuous consumption, people responded to that.

But as much as he didn’t seek it, I do think he relished fame. Most people relish fame for the wrong reasons - to be able to get into restaurants or preferential treatment or that kind of thing. Keith used it as a tool for good to do good things for others. By 1984 and 1985 he is globally famous, but he was never insanely rich. I don’t think Keith ever held a million dollars in his hand.

Foyer: In an exhibition full of memories, such as this, is there a work that stands out?

Vazquez: Most reminds me of him? The one that triggers a specific memory is A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat (1988). Because the day that he showed it at the Shafrazi show, it fell. It did not fall forward. It just slid down the wall, and it made a loud thud. And it stopped the room. And Keith, you know, he laughed and laughed and said, “that is Jean's way of telling us that he's here.”

Foyer: He was so incredibly productive towards the end of his life. Was there a change in his style coming?

Vazquez: He was determined to do as much as he could, until he could not anymore. But there was a stylistic change - the art he made that happened later, started to take on a more sort of collage, kind of vibe. It was less structured, less orderly. It was changing. He was as prolific in one decade as many artists are in a lifetime.

Foyer: The exhibition highlights his diverse material choices – wood, ceramic, metal, canvas. What inspired him to paint on tarps?

Vazquez: I see the tarps as an early show of rebellion. It reflected the street and the way we live. On streets and sidewalks New York Con Edison, the utility provider, used to cover their equipment at night with tarps. And he thought, oh, how interesting it would be to use a tarp to paint on, and being Keith, he researched what paint sticks best, and didn’t just experiment, but turned it into large scale works. He was an artist who loved to explore and push. Later on, he warmed up to canvas and would use it almost exclusively in his practice.

Foyer: How did you come to lead the Haring Foundation?

Vazquez: Keith was very instrumental, strategic even, in establishing the foundation during his own lifetime. It was Keith who asked me to be a board member on the foundation. I never had any inkling that I would ever run the foundation. It happened serendipitously. It was Julia, Keith’s former studio manager, the gatekeeper I had met back in 1988, who had run the foundation from its inception and following her decision to move on after thirty plus years, I threw my hat in the ring. My direct connection to Keith is unique and that we, as an organization, will not have forever. After me, it will be someone who likely never met him. It's a unique opportunity and I am proud to serve. I've been officially the executive director for two years.

Foyer: Artist foundations are typically about legacy preservation, but the Haring Foundation has so many social outputs, does so much work in communities. Did Keith have any idea how novel this was when he established it?

Vazquez: I mean, the foundation was modelled on the kind of work he was already doing. He was lending his talent to causes, he was making posters for them, he was donating money. He cared about kids a lot. He was a man that didn't forget or didn't unlearn how to be a kid and he wanted to protect that. The foundation was set up to be an organic extension of his own work. We took it from there., but let us be clear, none of us on the board had ever run a foundation before. So, it was up to Julia and to us to make it work. Those very first grants were quite modest - it would be like, $5,000, give or take. But it has grown, and we have grown, and the licensing business has really grown, and that growth allows us to be more generous, to support more organizations and communities.

Foyer: Most renowned artists have at least one museum dedicated to their work. A shrine of sorts. Did Keith want that?

Vazquez: It was something that Keith wanted. We, as a board very early on, investigated the feasibility of doing that while also doing the other work. And we felt that it would have turned into more of an expense, you know, a never-ending expense. So, we decided not to pursue that even though it is something that he wanted. And someday, it can be something that exists in a virtual way.

Foyer: Is it true the Pop Shop never made any money?

Vazquez: Yup. It was the logical extension of his practice after the subway drawings became unfeasible. And we kept it open for some years beyond reason, just to keep the spirit of it alive. But running a for-profit business while running a nonprofit is laced with conflict. It was not an easy decision at all, but we did shut it down in 2005.

Foyer: It has been 25 years since Haring’s first retrospective, and in that time, he has only become even more famous. Does the sun ever set on Haring?

Vazquez: Whether there are exhibitions happening, he is omnipresent. But it is because we all want this. We all need this.

***

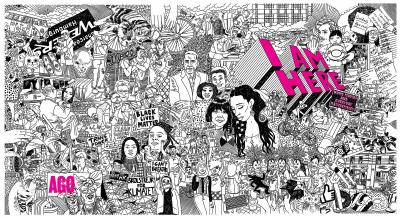

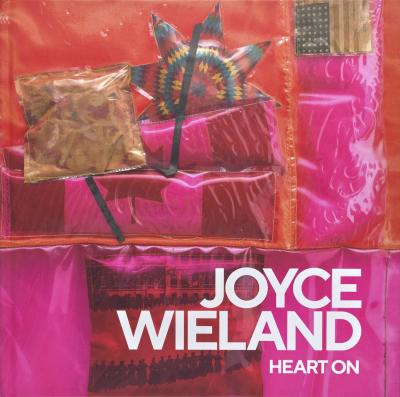

Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody is on view at the AGO until March 17, 2024. For entry to the Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody exhibition, purchase an AGO Membership or Annual Pass. Visit the AGO website for more details.

Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody is organized by The Broad, Los Angeles and curated by Sarah Loyer, Curator and Exhibitions Manager, The Broad. The AGO's presentation is curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, AGO's Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art.