Unpacking Identity With Louise Noguchi

The acclaimed Japanese Canadian artist reflects on her exhibition on view now at the AGO

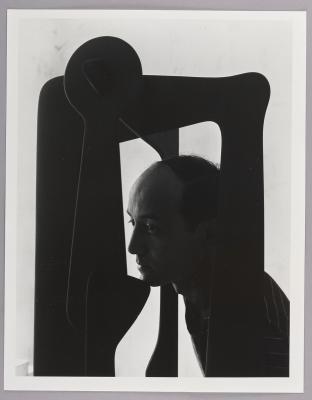

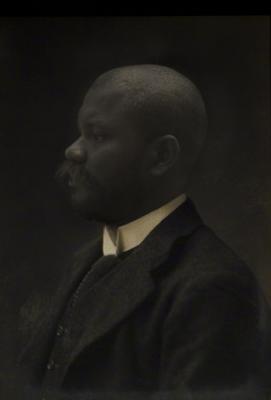

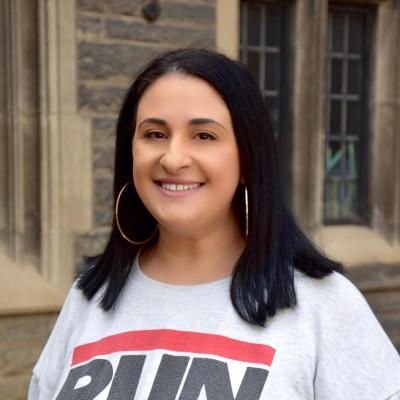

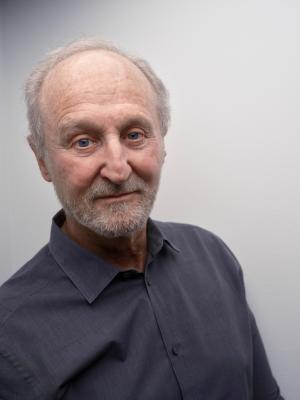

Portrait of Louise Noguchi. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

In preparation for her Language of the Rope series (1998-2005), acclaimed Japanese Canadian artist Louise Noguchi trained in the rodeo traditions of trick roping, bullwhip cracking, knife throwing and trick riding. She wanted to explore the idea of violence as a celebrated lifestyle. Since the early 1980s, Noguchi has been mining the complexity of human identity, documenting the many paradoxes and dichotomies of personhood. On view now at the AGO until July 27, 2025, her exhibition of three bold works exemplifies her distinct perspective.

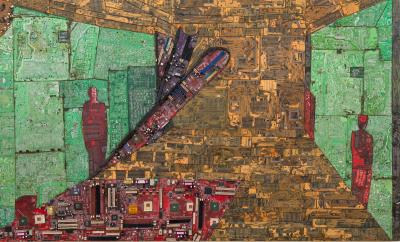

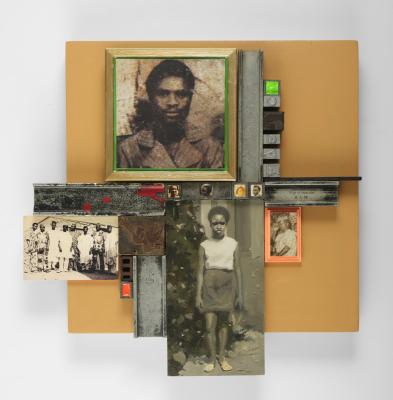

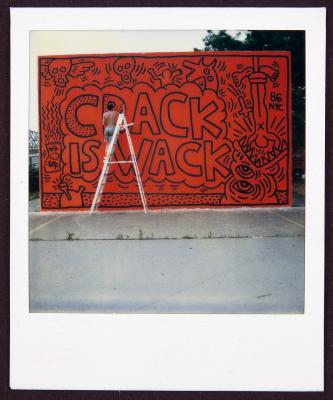

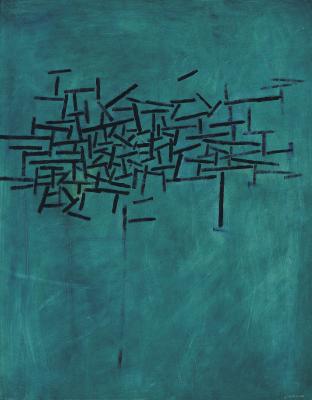

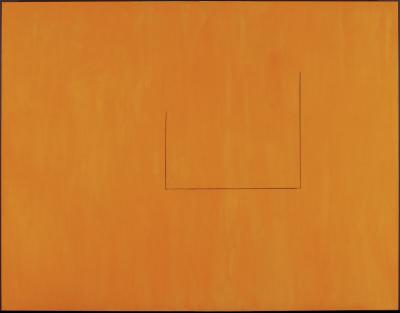

Curated by Renée van der Avoird, the AGO’s Associate Curator of Canadian Art, Louise Noguchi: Selected Works, 1986 – 2000 brings together three works highlighting Noguchi’s command of sculpture, installation and video. Crack (2000) is part of her four-video series Language of the Rope and sees the artist performing as an assistant in a wild-west act, holding out flowers only to have them suddenly cut down mid-air by a whip. Fruits of Belief: The Grand Landscape (1986) brings together a head, a cornucopia, and a photographic reproduction of Thomas Gainsborough’s 1770s painting, A Grand Landscape, to examine our shared relationship to nature. Finally, the mirror sculpture Eden (1990-91) addresses themes of surveillance and freedom, asking: are we approaching paradise, or withdrawing from it?

For Noguchi, her lifelong interest in identity begins with the juxtaposing victim/perpetrator narratives present in her Japanese Canadian heritage: the internment of her Japanese ancestors by the Canadian government (1942-1946), alongside the various atrocities committed by Japan during WWII. Born in Toronto in 1958, Noguchi graduated from the Ontario College of Art in 1981, and began a successful career working with sculpture, photography, and installation. She attended the University of Windsor in the late 1990s, receiving her MFA in 2000 and was a professor in the Art and Art History Program at the University of Toronto Mississauga and Sheridan College. Her works have been included in solo and group exhibitions across Canada and internationally.

Noguchi spoke to Foyer about Japanese Canadian history, rodeo apprenticeships, and her personal philosophy of the artist as a hunter.

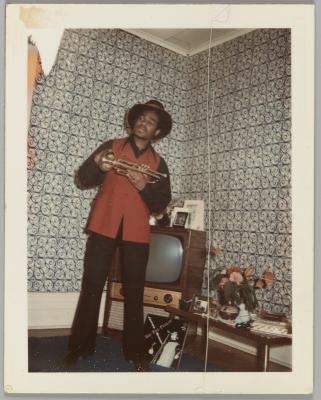

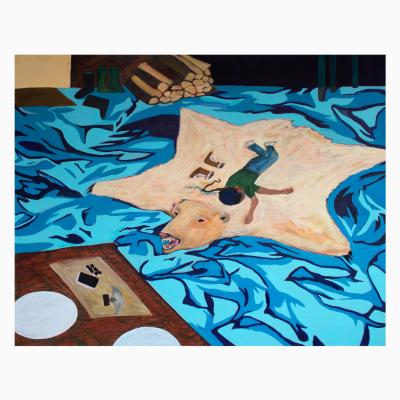

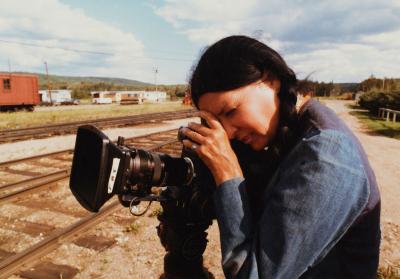

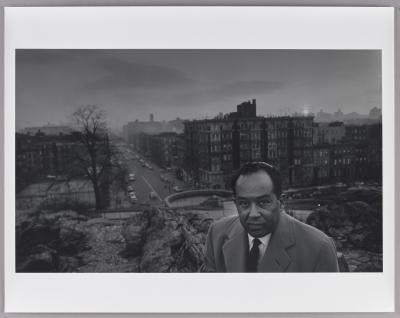

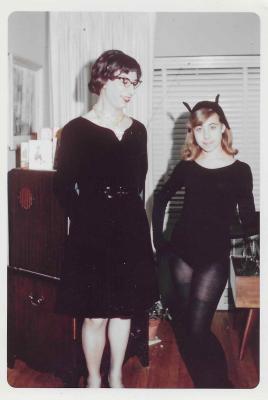

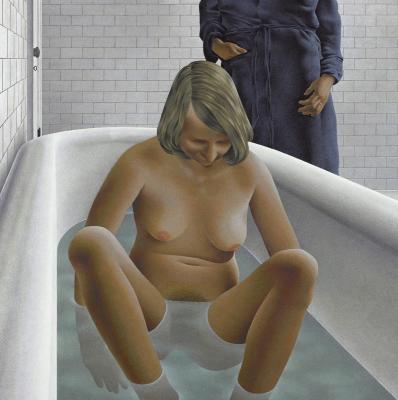

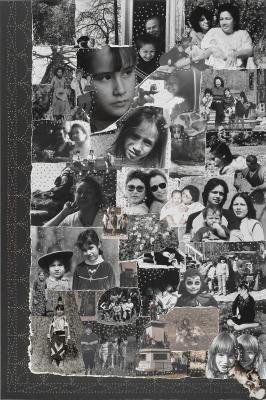

Louise Noguchi. Film still from Crack, 2000. Single channel DVD, video projection, colour, sound, Running Time: 3 Minutes. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchased with financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts Acquisition Assistance program and with the assistance of the E. Wallace Fund, 2004. © Louise Noguchi. 2004/43

Foyer: When speaking about your work, you’ve stated that it “has arisen out of [your] interest in the dichotomies that we use to identify and exist beyond our physical differences.” Can you unpack the meaning of that statement for us and share some of the ways it is exemplified in your work?

Noguchi: I always begin speaking about my work by talking about the artist as a hunter. The earliest works that I did came from the idea that the first artists were hunters, and they would draw from the hunt. When I was young, I didn't know who I was as an artist, or what an artist was exactly - which was a big question to answer – so when I looked at the history books, I realized that artists could have a connection to the hunt and possibly have a connection to the hunt today. Too often we romanticize what an artist is, and for me, the idea of the artist as hunter; someone that might not be quite reliable and might have their own agenda, was of an interest to me.

This does also relate to my identity as a Japanese Canadian and having a family that was interned. I’m third-generation Canadian, my parents were second generation, and my grandparents came here to Canada and they were interned. I have an ambiguous relationship with my Canadian identity, but also with my Japanese identity, because of what the Japanese had done during the Second World War and earlier. Even though my relatives didn’t participate directly in those atrocities, I cannot deny that heritage.

Crack is part of your Language of the Rope series from the late 1990s and early 2000s, which stems from the lessons you took in trick roping, bull whip cracking, knife throwing and trick riding. Can you share what inspired you to engage in this training, what it felt like learning those skills, and how that experience influenced your practice?

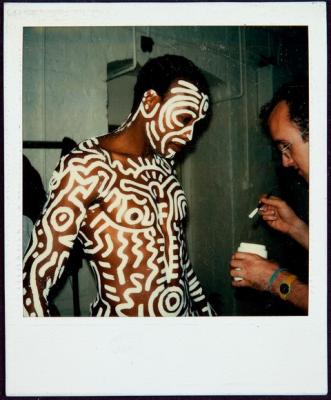

When I started graduate school, I was 40 years old and already an experienced artist, so I was looking to push my boundaries. My fellow students told me that my work was very violent. I never saw it that way, but they did. So, I decided that violence would be the theme that I would write about and pursue in my work. I decided to learn trick roping. However, my professors at the university said I wasn't good enough at trick roping and that I needed to find a trick-roping teacher. I found a teacher, but it took a long time to convince him to teach me. He was a professional rodeo person. He also did knife throwing, trick riding, and bullwhip cracking. I thought that was great because it all goes with the idea of violence. I thought I could learn from him about how violence can be made as entertainment, and various other ideas about violence.

I would take lessons each week. Maybe some of my fellow art students saw it as a cop out, me taking lessons from a professional cowboy, but it was all just researching and understanding. I never did become a great trick roper or knife thrower, but I am able to do some simple tricks.

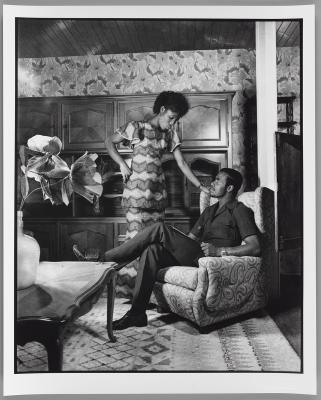

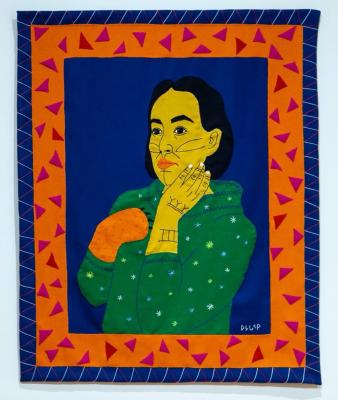

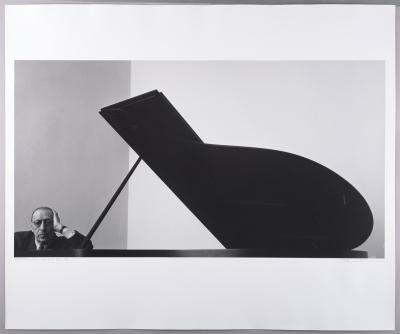

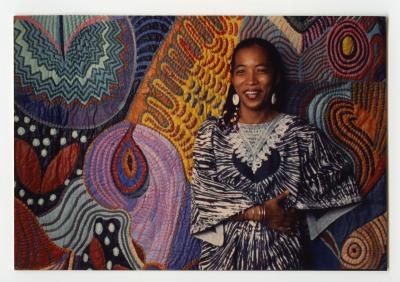

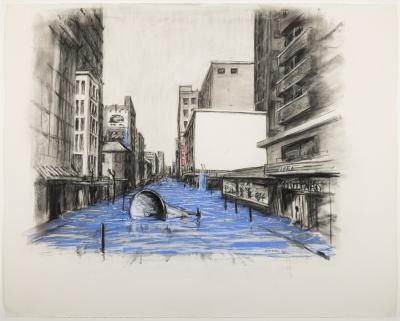

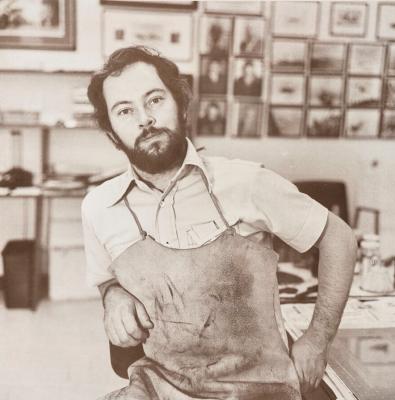

Louise Noguchi with Fruits of Belief: The Grand Landscape, 1986. Hardware, oil paint, oil stain, black and white photograph mounted on wood construction, wood, fibreglass, resin, epoxy glue, overall dimensions: 106.7 x 655.3 x 259.1 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift from the Phyllis Kurtz Fine Fund, 1988. Artwork © Louise Noguchi. Photo AGO. 88/335

In 1986, you made Fruits of Belief: the Grand Landscape and examined our relationship with nature. The panel text for this work suggests that you may be posing the question, “will our knowledge get us out of this mess we have made of the environment?” What are your thoughts about this work and its relevance 40 years later, and do you feel that the question you posed has been answered?

The question definitely hasn't been answered, but it's become more of a pressing question than it was back then. I was not only thinking about the environment, but also the hierarchy in society. In The Grand Landscape by Gainsborough, there is a couple depicted who are able to enjoy and frolic in the landscape, while you can also see another little fellow in the background who is obviously working maintenance to upkeep this pristine but natural looking environment.

I was asking a lot of those questions. I hope it will be resolved, but it's like the hunter and hunted question; there will always be the hunter and the hunted. As my father would say, “wars will never end, just take a look at the bird feeder, the birds are always fighting”.

Louise Noguchi: Selected Works, 1986 – 2000 is on view now, on level 2 of the AGO (in Irving & Sylvia Ungerman (gallery 230) and Jennings Young Galleries (gallery 231).