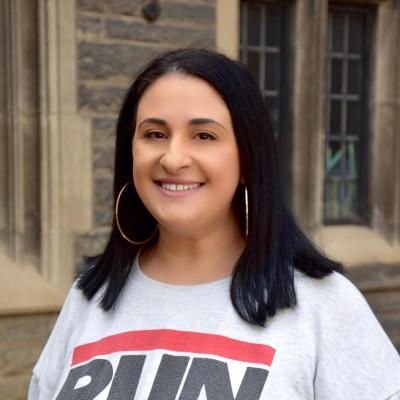

The Power of Words with Sarindar Dhaliwal

Dhaliwal writes about South Asian traditions and the concept of marriage in two short stories

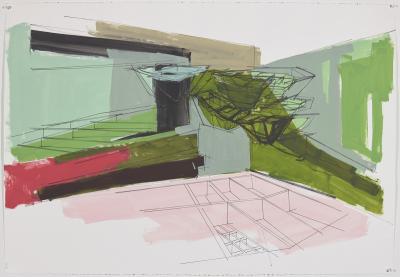

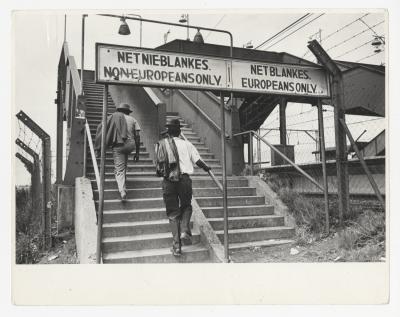

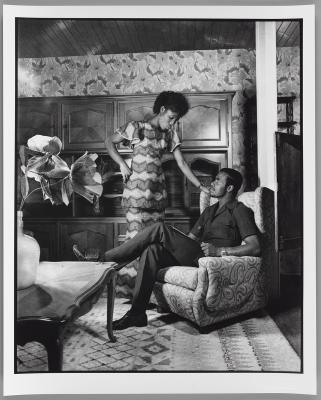

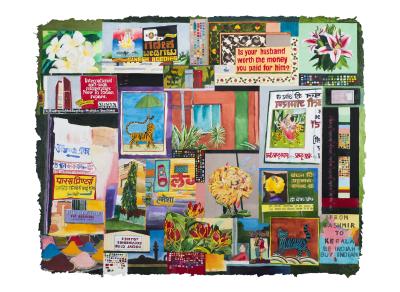

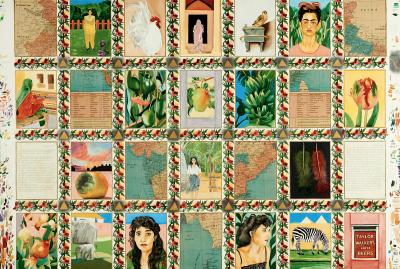

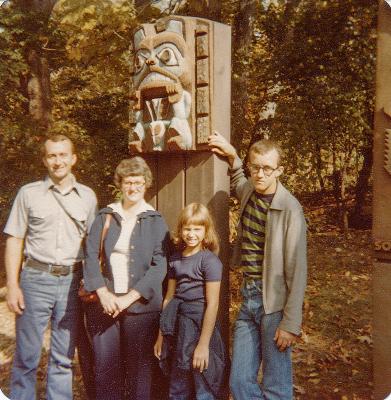

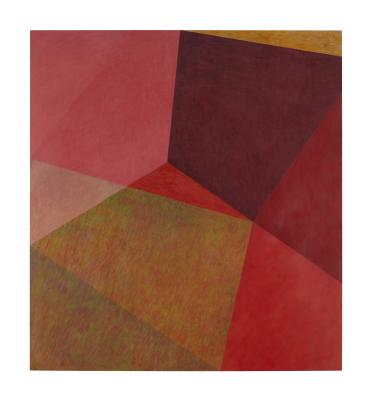

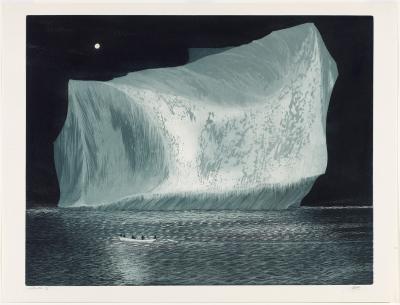

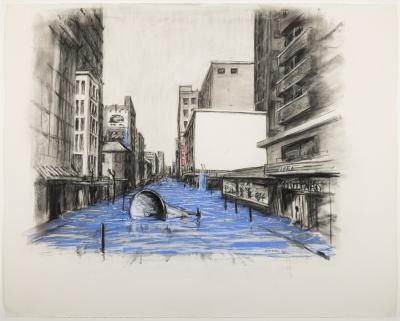

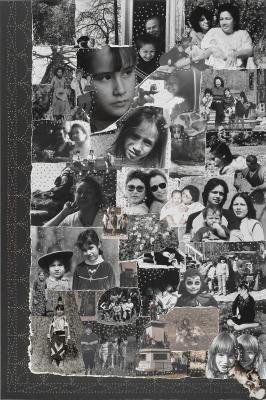

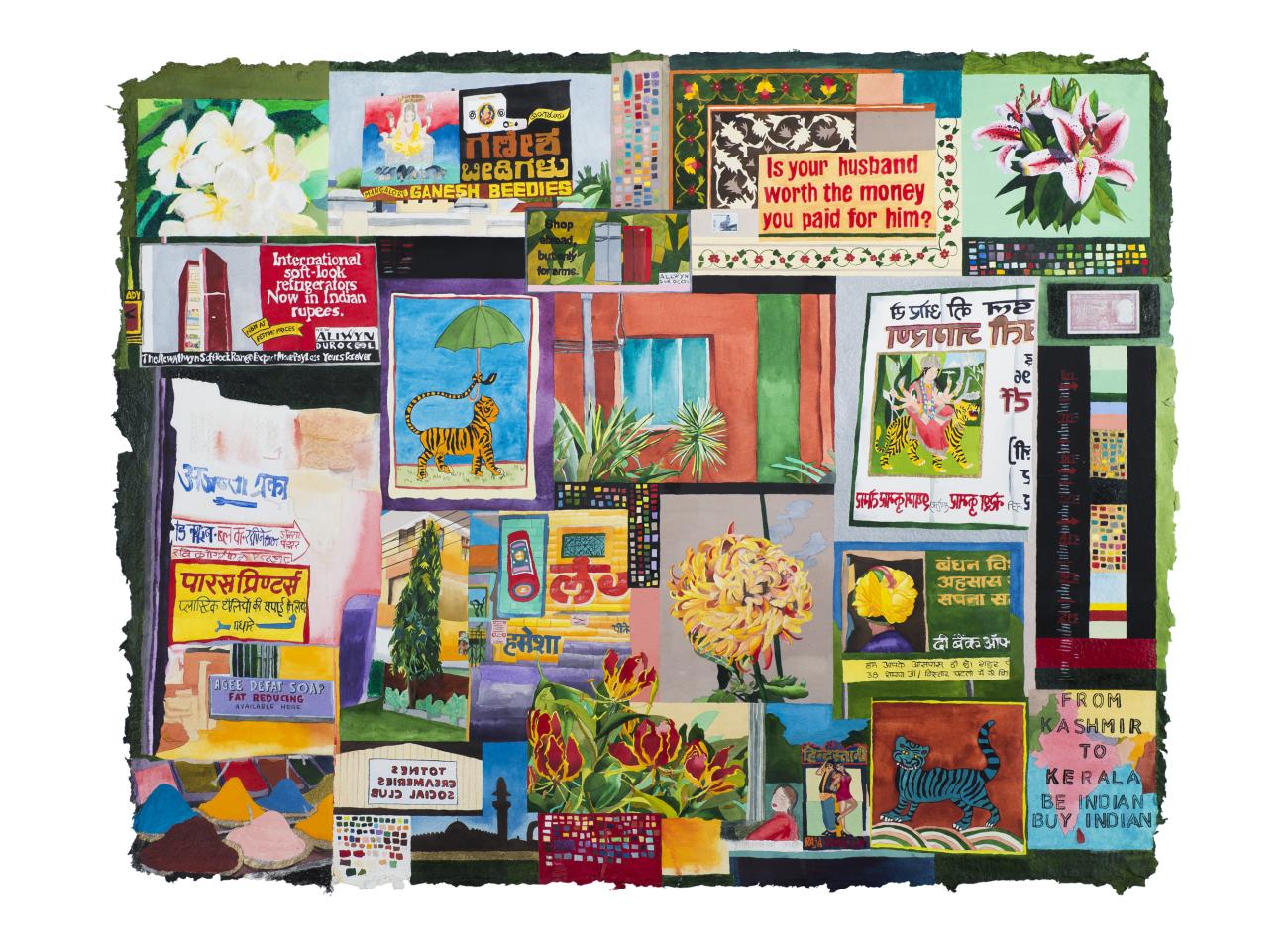

Sarindar Dhaliwal. Indian Billboard, 2000. Watercolour, oil pastel on paper, Overall: 127 × 153 cm. Collection of the Canada Council Art Bank. © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo: Brandon Clarida Image Services

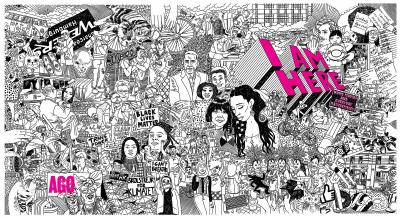

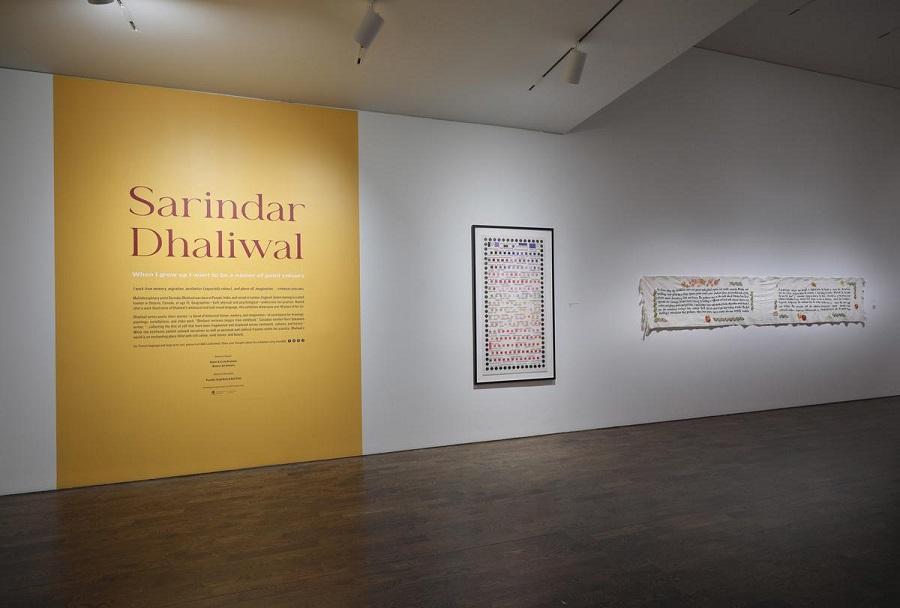

For Sarindar Dhaliwal, words hold power. They have gradually become a prominent aspect of her art throughout her decades-long practice, as seen in her solo AGO exhibition When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours. What started as one or two words featured in her art, eventually became an elaborate tapestry of short stories like The First Wedding (2023).

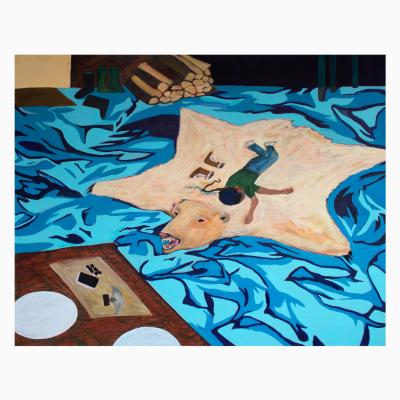

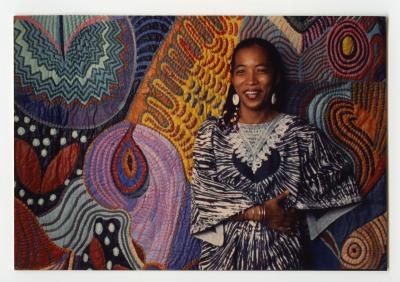

Spanning 17 feet long, The First Wedding (as seen in the image below) is made from a piece of cotton Dhaliwal rescued from the village where she and her mother were born. Her mother picked, spun and wove the cotton, and many years later, Dhaliwal asked a woman artist she knew to do the embroidery. Surrounding the embroidered text are colourful motifs, which frequently appear in her other works like Indian Billboard (2000) (image above) and Peonies II (1997). Beautiful tiles from the buildings in Lisbon, Portugal she encountered in her travels also inspire these motifs.

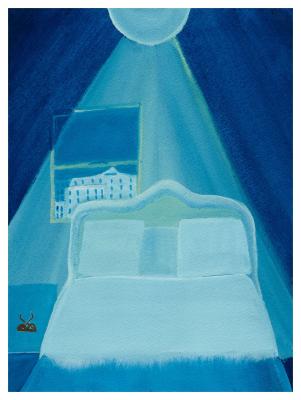

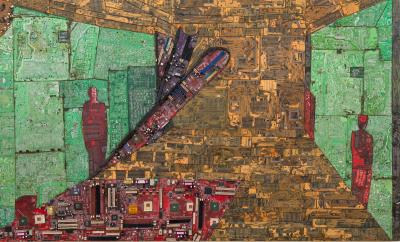

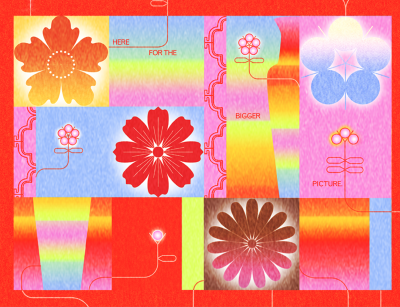

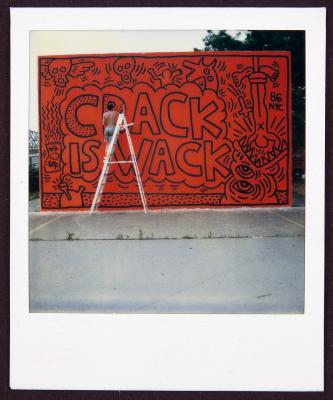

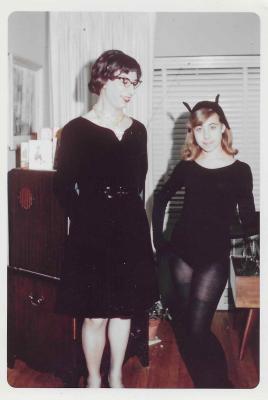

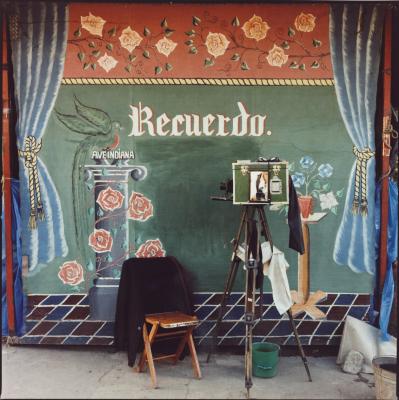

Installation view, Sarindar Dhaliwal: When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours, July 22, 2023 - January 1, 2024, Art Gallery of Ontario. Works shown: When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours, 2010; The First Wedding, 2023. © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo: AGO

The embroidered text tells a short story about the first wedding Dhaliwal went to as a child when she was around seven years old. She writes about her mentally unstable cousin’s arranged marriage to a young girl from Punjab, India. Under these circumstances, traditionally, the bride and groom do not officially meet until the marriage ceremony. Dhaliwal wonders what the girl will say once she finally sees the face of her future husband. She then goes on to describe the gurdwara, where the two get married. She highlights the contrast of the dinginess of the old gurdwara to the well-kept beautiful public library where Dhaliwal frequently visited. She elaborates on the one-sided intentions of the groom’s mother, who only wishes her mentally unstable son to have a “normal life” and be married. A critique to the institution of marriage, this short story invites the reader question what young Dhaliwal thought at the time. What about the girl’s future? What about her happiness? Why does no one care?

The text on the embroidery says:

In those days the gurdwaras were not graced with gilded cupolas and marble minarets. Worship, and weddings took place in a dingy upstairs public rented room. Linoleum floors and panelled walls of fake plastic wood. Everything dark and dreary. The gurdwara was on the south side of Osterley Park Road opposite the Carnegie funded Public Library. A building so different; red brick with classical columns and arches and glossy green and gold tiles. I would totter home with stacks of books. My mother would shout at me, she considered reading a lazy activity. “You’ll fail at school if you keep looking at books.” The first wedding I attended at that gurdwara, when I was seven, was a cousin’s who was mentally unstable.

A sixteen-year old girl was brought to England from the Punjab to marry him. She had never met her future husband before the ceremony. I kept asking my mother “What will she say when she sees his face?” I remember laying my head on her knee – the patterns of the fabrics of her salwars embedded in my memory: acorn shapes in a sea of yellow joy, creamy tree branches on a burgundy background. She explained that his mother wanted him to have a life with a wife and children. This encounter with the unfairness demonstrated towards females in that patriarchal culture shaped my relationship with my extended family but also the world at large.

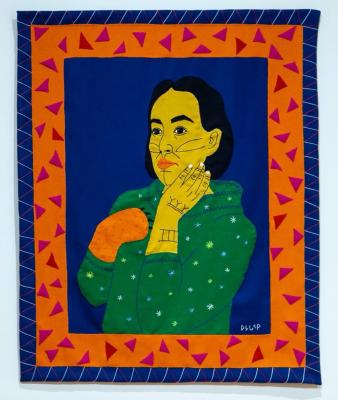

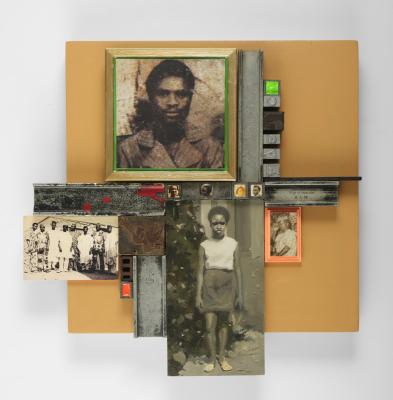

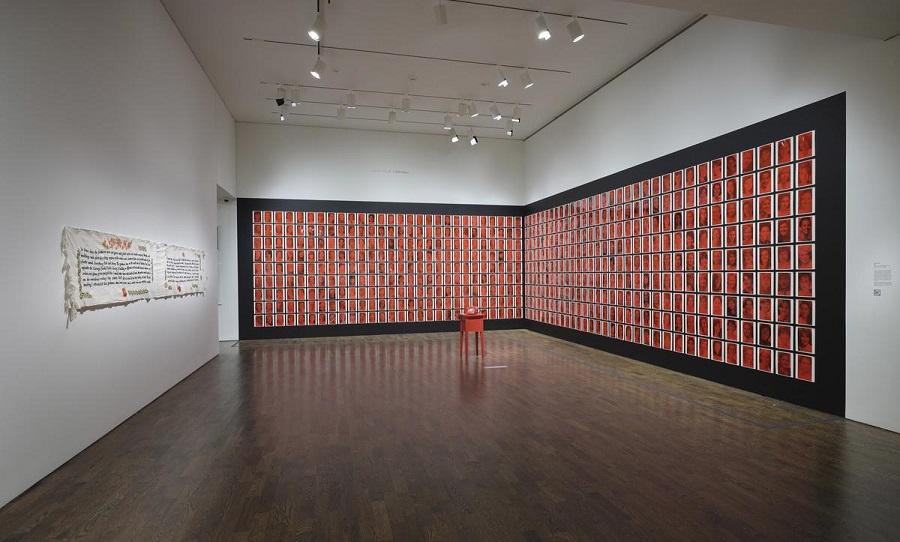

Installation view, Sarindar Dhaliwal: When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours, July 22, 2023 - January 1, 2024, Art Gallery of Ontario. Works shown: The First Wedding, 2023; Hey Hey Paula, 1998 © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo: AGO

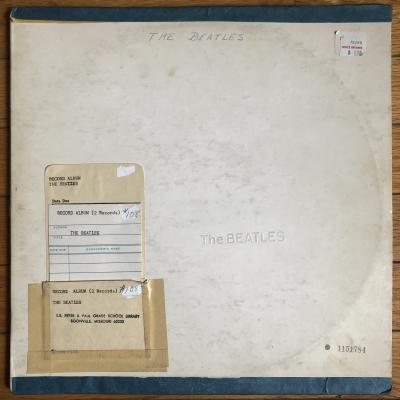

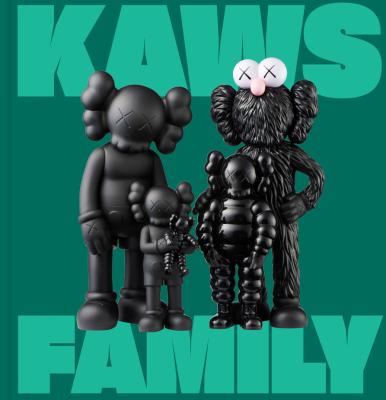

In Dhaliwal’s AGO exhibition, The First Wedding is carefully placed adjacent to Hey Hey Paula (1998), a multimedia installation featuring 544 photographs of brides-to-be who are mostly white, pearl-clad women, as seen from New York Times engagement announcements from 1989 to 1992. Placed in front of the hundreds of photographs is a red telephone that plays the 1963 ballad Hey Paula by American pop duo Paul & Paula – a song that emphasizes the mythology of Western romantic love. Hey Hey Paula presents a Western parallel to the South Asian practice of arranged marriage in The First Wedding.

The critique of marriage for Dhaliwal dates back to the 1980s when she had written a short story titled The Unsuitable Suitors centred on the tradition of arranged marriages in South Asian culture. A great juxtaposition to the story in The First Wedding, it describes an eager meeting by two families to have their son and daughter meet as potential marriage partners. It tells the story of a woman – Dhaliwal’s cousin – who had not found a suitor she liked from her family’s many recommendations and was shocked by a surprise visit of one. It shares how, cousin B. as Dhaliwal refers to her, took one sneak glance at the potential suitor from a distance who showed up at their doorsteps uninvited and immediately rejected him and the chance of any courtship. This story poses a stark contrast to The First Wedding, which highlighted the differences in prioritizing happiness between men and women in an arranged marriage. Unlike The First Wedding, Dhaliwal’s cousin B. in The Unsuitable Suitors was able to hold her ground and take control of her future – though according to Dhaliwal, she has been unhappy with her husband for decades and has said she was pressured into that marriage.

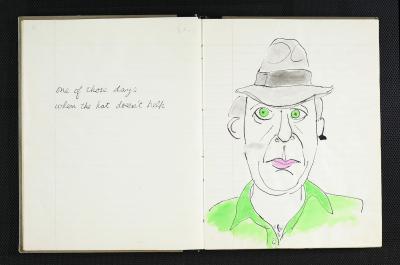

The Unsuitable Suitors (1980s)

My cousin B. was twenty-six by the time she finally agreed to marry someone. She had been peevish about the whole business for several years, blaming the family for not trying hard enough to locate a husband worthy of her. The suitors had been paraded before her in person, via photographs and she sulkily and haughtily rejected each one.

In 1972, my grandfather, who was living in Glasgow, had a conversation with a neighbouring woman. “We have a nephew living in Vancouver,” she mentioned casually. “Why,” replied my grandfather, “My middle daughter’s eldest girl is in Toronto.”

The telephone rang on Brunswick Avenue. Long distance from the West Coast. However, marriages cannot, even in this day and age, be negotiated over the phone. Send a letter (enclosing a picture) urged the Brunswick Avenue clan. To the family’s surprise, the very next day an eager uncle accompanied by the hopeful young man arrived at Malton airport.

B. sneaked one sidelong look at the boy from outside the doorway. She sniffed and turned away. “He’s too short and besides he has a long nose,” she stated flatly and stomped off. Another quick courtship.

Sarindar Dhaliwal: When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours is on view until July 14, 2024 at the AGO on Level 1 in the Philip B. Lind Gallery (galleries 131 & 132). A small installation of five works by Dhaliwal will go on view on August 5, 2024, in the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art on Level 2 of the AGO.