Jeff Thomas’s urban vision

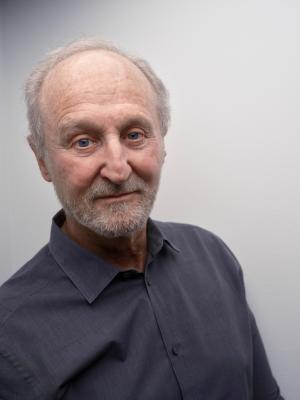

The Iroquois photographer reflects on four decades of image making

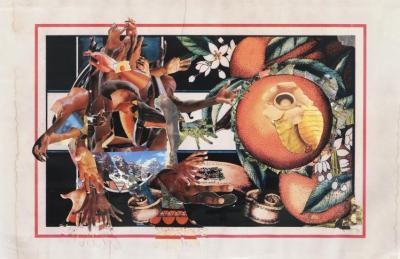

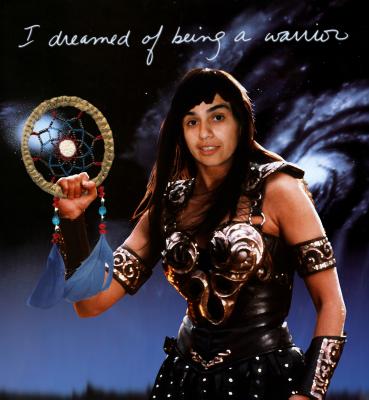

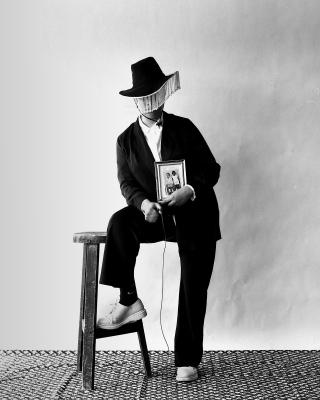

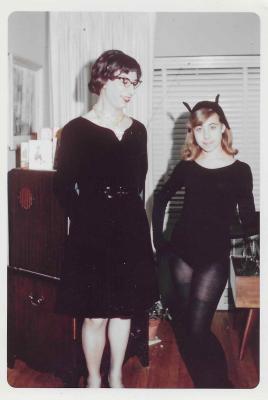

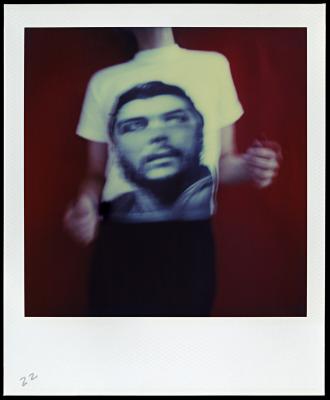

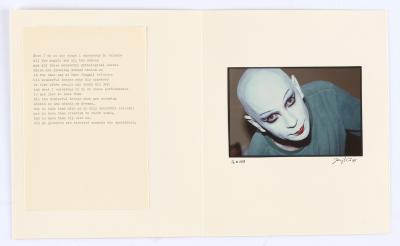

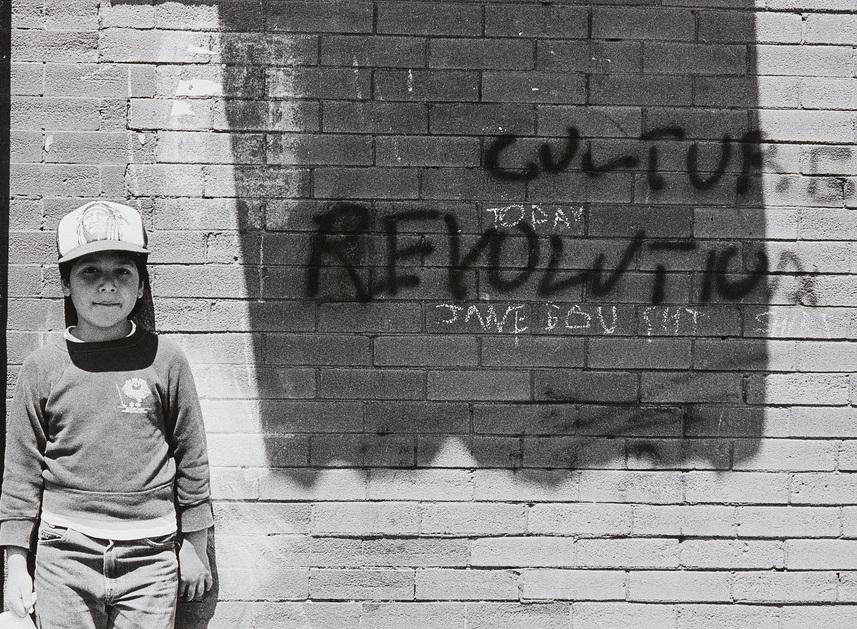

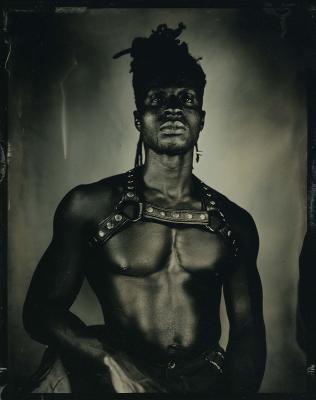

Jeff Thomas. Culture Revolution Today, 1984, Toronto, Ontario, N43 38.958 W79 23.638, 1984. pigment print on archival paper, Overall: 71.1 × 91.4 cm (28 × 36 in.). Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase with assistance from an Anonymous donor and James Lahey, 2016. © Jeff Thomas. 2016/44.1

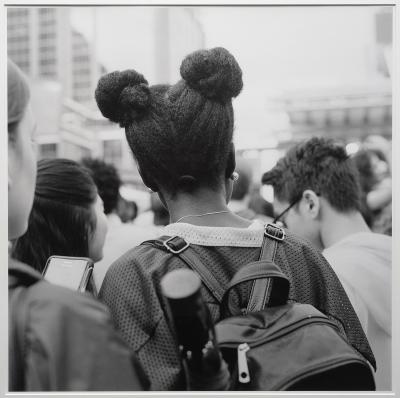

Drawing on an array of image-based works from the AGO Collection, a new exhibition entitled Cities in Flux features a selection of 100 photographs depicting urban centres around the world. This visual exploration of the economic, political and cultural realities of city life is curated by Marina Dumont-Gauthier, AGO Curatorial Fellow, Photography, and brings together the work of Berenice Abbott, Bhupendra Karia, Paul Kodjo, Diane Liverpool and over 40 other artists.

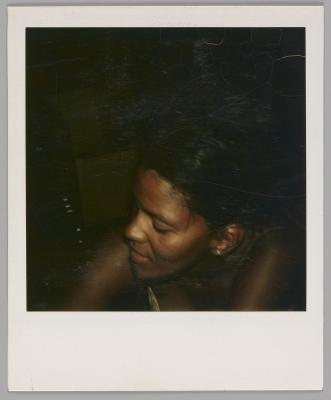

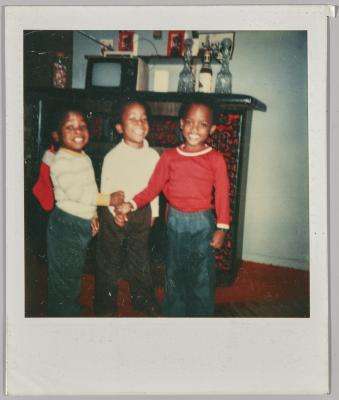

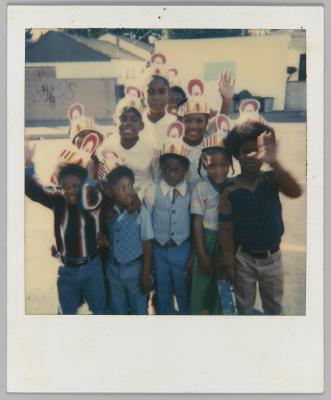

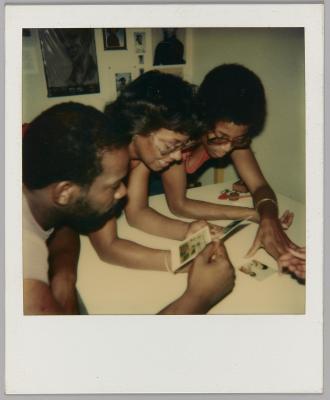

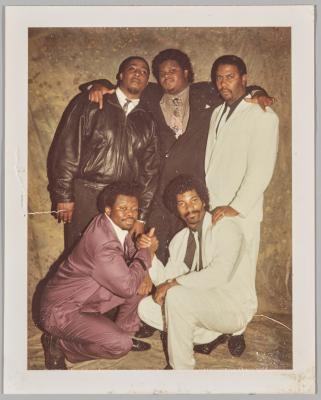

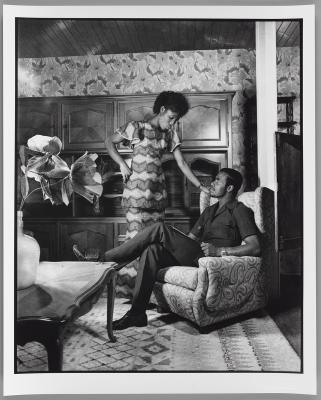

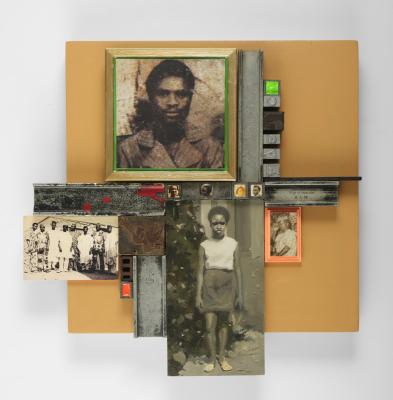

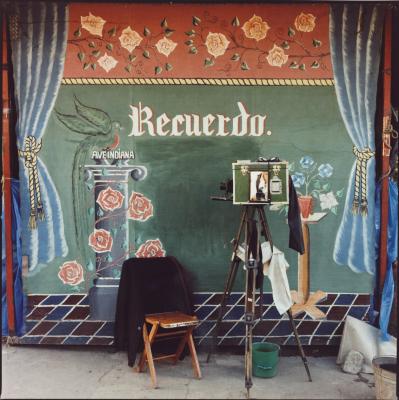

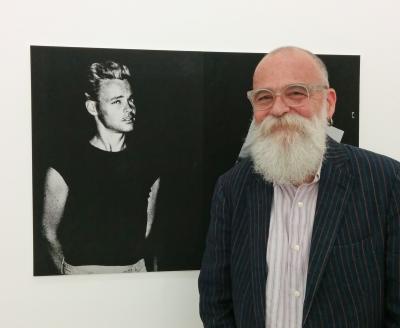

Among them is photographer, curator and cultural theorist Jeff Thomas. Self-described as an Urban-Iroquois, Thomas’s photographic practice of 40 plus years re-contextualizes historical images of Indigenous peoples and communities. Four works by Thomas are part of Cities in Flux, all depicting Toronto in the early 1980s – a period when he had just relocated to the city from his hometown of Buffalo, New York. Two are striking portraits of his son, Bear, and the other two capture storefront images on Queen Street West (including the well-known Algonquin Sweet Grass Gallery) . Thomas would later move to Ottawa, where he worked in the National Archives of Canada, developing appropriate captions to replace dated terminology used to describe their collections of photos of Indigenous Peoples. He continued to develop his multi-disciplinary practice in the years following, unveiling many acclaimed works, series and exhibitions.

We connected with Thomas to find out more about his bold approach to image making and his practice at large.

Foyer: You moved from Buffalo to Toronto in 1984, the same year you photographed the Algonquin Sweet Grass Gallery on Queen Street West. How would you describe Toronto at that time? How would you describe your experience living here?

Thomas: Toronto was very different from Buffalo, New York, where I began my career. Toronto was busy and clean. And by that, I mean it was not a post-industrial city. When I began photographing along the streets of downtown Buffalo, it still retained the old city architecture. Although the rise of suburban malls had gutted the downtown stores, downtown had a character I liked. I found a bit of that character along Queen Street, but my Toronto photographic experience was transitional and needed a new direction.

Foyer: Culture Revolution Today, featuring your son Bear, was also shot in 1984. This photograph represented a pivotal shift in your practice and your approach to image making. Can you elaborate on this moment?

Thomas: Culture Revolution was a transitional image for my work as a street-based photographer that took place in 1984 and marked a point when I asked myself, what stories was I going to tell my son?. I didn't have a father who helped me navigate the complicated landscape of the reserve and city. The image I made that day marked the beginning of a ritual between son and father and culminates in my 2024 exhibition, The Stories My Father Never Told Me, at the Ottawa Art Gallery.

Foyer: You’ve described yourself as Urban-Iroquois. Could you share your definition of the term and describe what led to you creating it?

Thomas: My self-identification of urban Iroquois began without any known photographers who focused on the urban Indigenous experience. I was born and raised in Buffalo, New York and I am also a member of Six Nations of the Grand River. I was fascinated by the dichotomy of the two realities. I remember the turning point for self-identification coming when it was assumed I was born on the reserve. Not all Indians were born on a reserve like my parents and grandparents.

Foyer: You worked with the National Archives of Canada in the 1990s. How would you describe your role there? How did your work in that role influence your photography practice?

Thomas: I moved to Ottawa in 1993 [which is] when I discovered that Library and Archives Canada had the complete twenty-volume set of famed photographer Edward S. Curtis' The North American Indian. My first contract with the LAC involved writing new captions for photographs of Indigenous people with captions using words like squaw, redskin, and half-breed. In 1996 I was invited to guest co-curate a survey exhibition for LAC Aboriginal Portraits and this project led to a new career as an independent curator. My LAC experience was transformative as a form of social action.

Foyer: What does your current photography practice look like? What are you most inspired to photograph these days? Are you currently working on any projects you can share details about?

Thomas: I am currently working on a solo exhibition for the Ottawa Art Gallery in 2024, the title is The Stories My Father Never Told Me. It is the culmination of my four decades as a photo-based storyteller and incorporating new technology as an element. I am focused on mining my archive of personal work and my research archive to build what I call post-reserve stories.

Cities in Flux is on view until December 3, 2023 on Level 1 of the AGO in the Edmond G. Odette Family and Robert & Cheryl McEwen galleries (128 and 129).

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)