Light shines out of darkness

Moridja Kitenge Banza talks art, colonial histories and Catholicism.

Installation view Murray Frum Gallery: Et La Lumière Fut (And There Was Light), November 2021 – June 2022. Artwork © Moridja Kitenge Banza. Image © Art Gallery of Ontario.

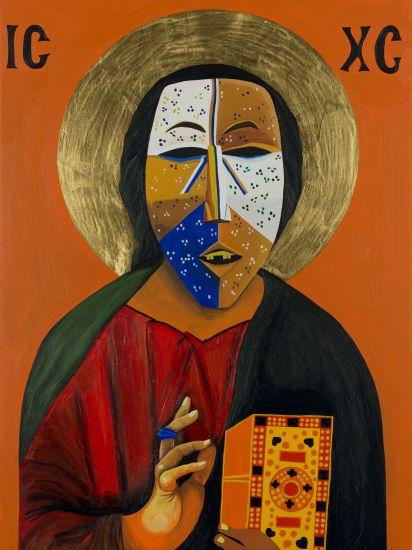

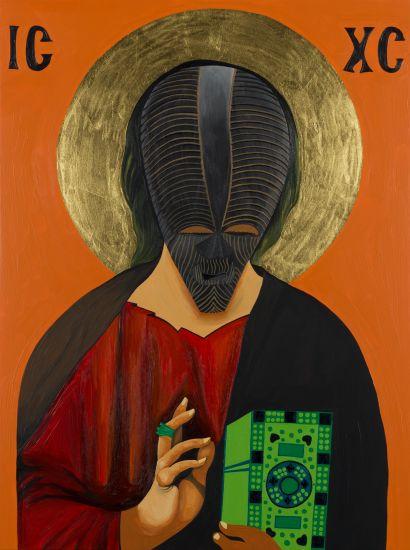

Moridja Kitenge Banza migrated to Canada in the mid-2000s from his home in the Democratic Republic of Congo, eventually settling in Montréal, Québec. A prolific multidisciplinary artist, Kitenge Banza is best known for his paintings: among the most recognizable, his Christ Pantocrator series. Referring to Byzantine Christian iconography of Christ Pantocrator, Kitenge Banza replaces Christ’s face with that of an African mask inspired by those made and worn by the Dan peoples of Liberia. This hybridization of aesthetic and symbolic representations mirrors Kitenge Banza’s complex reckoning with Christian indoctrination, the violent legacy of colonization and subsequent erasure of Indigenous Congolese spiritual practices. Through an autobiographical lens, Kitenge Banza parses through these inextricably linked narratives, reclaiming them and putting forth a transformative one.

Kitenge Banza’s 13th painting in the Christ Pantocrator series cements an important moment at the AGO, becoming the first acquisition by the Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora curatorial department, led by AGO Curator Dr. Julie Crooks. Et la lumière fut: And there was light, [previously on view at the AGO], marks the first exhibition of a contemporary artist in the newly revamped Murray Frum Gallery at the AGO. The installation combined 13 new Christ Pantocrator paintings and three stained-glass works.

Kitenge Banza spoke with us while installing his exhibition in Frum Gallery, graciously illuminating us with deeper insights about his work.

Foyer: Does this exhibition, Et la lumière fut: And there was light, mark the end of the Christ Pantocrator series?

Kitenge Banza: Yes, for the moment, it marks the end of the creation of this series. When I started thinking about this series of paintings, I decided to make 50. I don't know why that number, but I wanted to make several of them, and spread them around the world. The project's ultimate goal was to make a chapel in which I would collect all these icons.

I’ve always had the idea to make a chapel, but I didn’t know when or where it could happen. When Dr. Julie [Crooks] called me to discuss the exhibition, she asked if I wanted to make a chapel now and I thought, “if I don’t make a chapel now with this offer at the AGO, I don’t know when I’ll have the opportunity to.” The decision to say yes was also personal to me because around the same time, many people in my life had passed away. That created a sense of urgency and pushed me to move forward with the idea. Also, the space at the AGO, because of its openness and structure, is well-suited to display stained glass. I don’t know if there will be a second chapel or a continuation of the series, but the paintings and stained-glass works are all new. Everything is new work.

Is this the first time you’ve worked with stained glass?

Yes, it is. I had the idea to work stained glass for a long time. Originally, I wanted to make real stained-glass works, but with the time and circumstances we had for the exhibition, it wasn’t possible. Instead, I chose to work with Plexiglas. I researched the history of stained glass because I wanted the reasoning to be clear. I thought about which images would be best to apply to stained glass and which ones might not be.

In the panel text for the Christ Pantocrator and stained-glass pieces, it refers to you thinking about this work and this chapel as a place of spiritual intention. Any ideas why we associate coloured light and stained glass with spiritual intentions? Is there some quality that you think of that lends itself to spiritual and meditative reflection?

That’s why we’re playing with the light and stained glass. Although the AGO is an art museum, I wanted the space to be like a Christian Church or religious space. For me, that was very important too, because of my Catholic faith. I go to Church regularly. From my understanding, most religious buildings are quiet, contemplative, safe spaces. People go there to speak with God and to build that connection. If you need to be plugged with God, you go to Church.

Within the context of the violent legacy of colonization in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I want to use this space to invite people in and shift their understanding of the role of the Church in the history of colonization. This space isn’t about the Bible, it’s not intimate or spiritual. It’s pulled from reality. At the time of colonization [in the Democratic Republic of Congo], people could not understand why the same people who were telling them to pray to God, were the same people that brutalized them. I hope people will see through this work that I’m not just black or just an immigrant, I embody the complexity of this history and the country I was born in. I made this work so I could understand this history as well, it’s not just for other people. I want to understand how religion started, what colonization does to people and so on.

It's beautiful, moving work. Have you been back to the Congo recently? Do you go back often?

Yes, we do go back. Not recently because of COVID. If it wasn’t for the pandemic, I would have finished a movie that ties in with this work. The idea started when I saw a mask in a fine art museum in Montréal that was from my mother's ethnic group called Suku. For the movie, I wanted to film myself visiting Congo and speaking with my grandfather, who is the leader of one of the Suku clans and showing him the photo of the mask. Then, I would bring him to Montréal to see the mask in person. But with COVID, that idea is on hold. I usually go back to Congo every two years and I speak with people there every day.

Your work is unique and personal to you. Are there other artists in the Congo addressing a similar loss of Indigenous spirituality in different ways?

That's a good question and many artists are. My work about the Congo and colonization is linked to what happens in Canada, Australia and other countries with similar histories of Indigenous people and erasure. Every country lives with colonization, it transforms people. It’s so difficult to go back and retain that knowledge and history that was taken. Many artists from the Congo are addressing colonization but maybe not so much with religion and Catholicism. I can’t say for sure but when I started this work, I didn’t see many artists exploring religion in this way. For me, it was accessible because I’m a practicing Catholic myself and my family is very religious. I know firsthand how it works and because of that, I can speak to it with my art.

The panel text is in English, French and Lingala. Tell us more about why you chose to present the text this way.

Lingala is one of the languages we speak in the Congo. For me, it's very important to speak to my community living here in Canada. It’s not because they don't understand French or English. It’s because I want to speak to them in our language. Even though I’m a Canadian now, I will always be Congolese. But for me, too, it's similar to when during colonization when people came with a flag to say, “this is my land, I'm present here”.

It was very important to put the panel text in Lingala, so thank you to the AGO for doing that. This is a first for me. When I was speaking to Julie, I thought it is time that I change my website as well to include Lingala. I grew up speaking French, I think in French and practiced my English when I moved to Canada. With this work and this exhibition, this is the first time I’ve thought about my work in my language.

In terms of self-identification, you refer to yourself as both Congolese and Canadian. Do you prefer to be called a Canadian-Congolese artist? A Congolese artist?

It depends where I am. I choose when I can have power. I decide when I can be just Congolese, when I can be Congolese-Canadian and when I can just be an artist. For an exhibition like this, I do have the power to choose. That said, being able to make those distinctions doesn’t change who I am and what I’m about. I know who I am and that’s important. At the same time, it’s important to say I’m a Canadian artist because that is part of my story as an immigrant. If someone wants to talk about Canadian art history, they can include artists like me. In that way, it’s political. If they don’t mention that I’m Canadian, they can make it so I don’t even exist in this history.

Last question. You’re in Montréal, and your art is gaining a lot of attention and praise which must be exciting. In terms of art, what excites you presently? What are you looking towards for inspiration?

There are many things that excite me right now. I'm looking at the BIPOC art scene a lot and my place in it and in the new narrative that we are all inscribing into the history of art in Canada. I'm thinking about how my work should be more present in all of Canada. I am also interested in the different technical aspects of my new works. I am thinking about the integration of digital 3-D in my work for example. I’m thinking about the present and the future.