Painted Presence

Co-curators Adam Harris Levine and Suzanne van de Meerendonk discuss what makes a Rembrandt

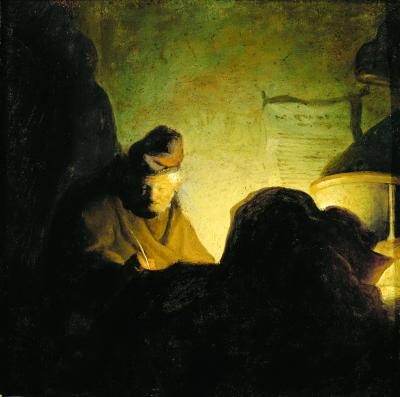

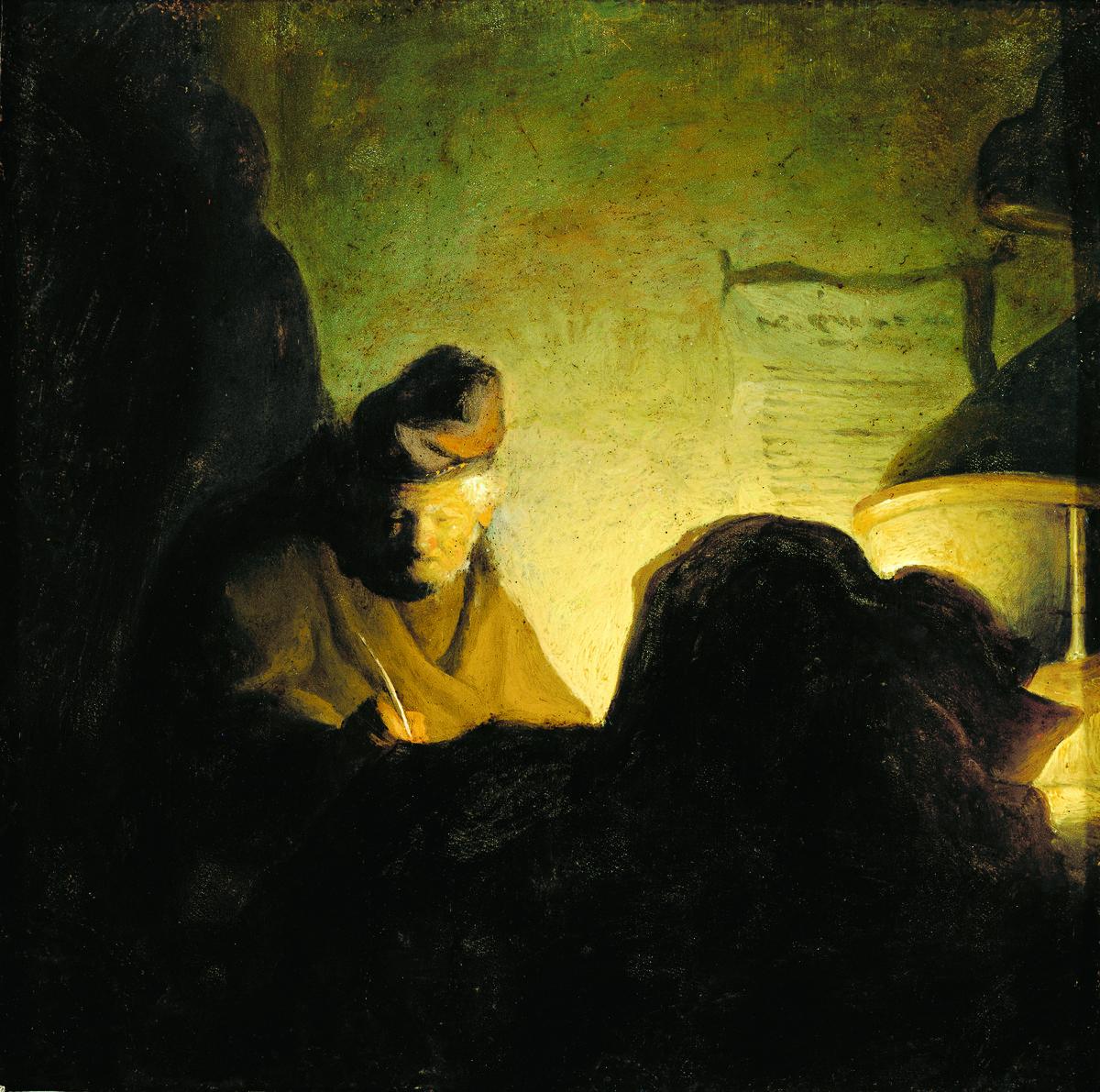

Rembrandt van Rijn (attributed to), A Scholar by Candlelight, around 1628–1629. Oil on copper, 13.9 x 13.9 cm. Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Gift of Isabel Bader, 2019 (62-004.02). Photo: John Glembin

In a rare and remarkable assembly, Painted Presence: Rembrandt and His Peers at the AGO, features seven works by or attributed to the great 17th-century Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). Rembrandt’s prominent status in Dutch art – as a painter and a teacher – was first seeded in the 1630s, when the wealthy upper classes flocked to his studio hungry for works by an ambitious young artist. 400 years later, his status has only grown, his name now synonymous with painterly genius.

To better appreciate both his enduring power and the tricky and often subjective task of defining what makes a Rembrandt, Foyer caught up with Painted Presence co-curators Adam Harris Levine, AGO Associate Curator of European Art and Suzanne van de Meerendonk, Bader Curator of European Art, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University.

Foyer: What accounts for Rembrandt's staying power?

van de Meerendonk: It is not one thing, but rather a constellation of factors that account for his enduring appeal. Rembrandt as an artist was extremely interested in what made people human. His portraits have an emotional depth, they radiate character – qualities that not all artists at this time were pursuing in the same way. People relate to that aspect today, I think, because it feels so unfiltered, despite our recognition that these portraits are not an unvarnished truth, but very much constructed. And of course, the myths around him, built over the centuries, endure because they are so compelling. We cannot forget that his position as a national hero in the Netherlands was also part of a larger nation-building project that gained momentum in the 19th century and arguably continues today.

Levine: We do not know the identity of any of the subjects in the Rembrandt paintings in this exhibition. And yet - visitors come away with these firmly rooted senses of the people they are looking at. That, to me, is such a testament to Rembrandt's skill. There is a small work in the exhibition, A Scholar by Candlelight, that has such a glow to it, that I like to joke that it looks like it's plugged into the wall. It could be one of the very few surviving Rembrandts from this period painted on copper. When we speak of Rembrandt’s brilliant use of light – this moody, intimate, cozy image of an old man, illuminated by a hidden light source against a shadowy backdrop - is what we are talking about.

What do the myths about Rembrandt get wrong?

van de Meerendonk: First and foremost, we know now that he was appreciated in his own time and was certainly not a misunderstood, lonely genius, but in fact the head of a large workshop of artists, whom he taught and collaborated with. Over the second half of the 20th century, art historians did a lot of work to debunk that myth, and to learn more about the artists who trained and worked in Rembrandt’s studio. Because of that research, many pictures previously attributed to Rembrandt were re-attributed to members of his workshop. That is part of why, in addition to authenticated works, we chose others that are either attributed to Rembrandt, previously attributed to him, or now convincingly attributed to people that Rembrandt worked with.

Levine: When we say 'attributed to' – art historians mean that a work is thought to be by an artist, but that there is no consensus amongst scholars. A term that has fallen out of fashion in museology is “given to.” Personally, I like that better, as it acknowledges that, in lieu of a signature, someone has said that they believe that it is by this artist – it feels more generous.

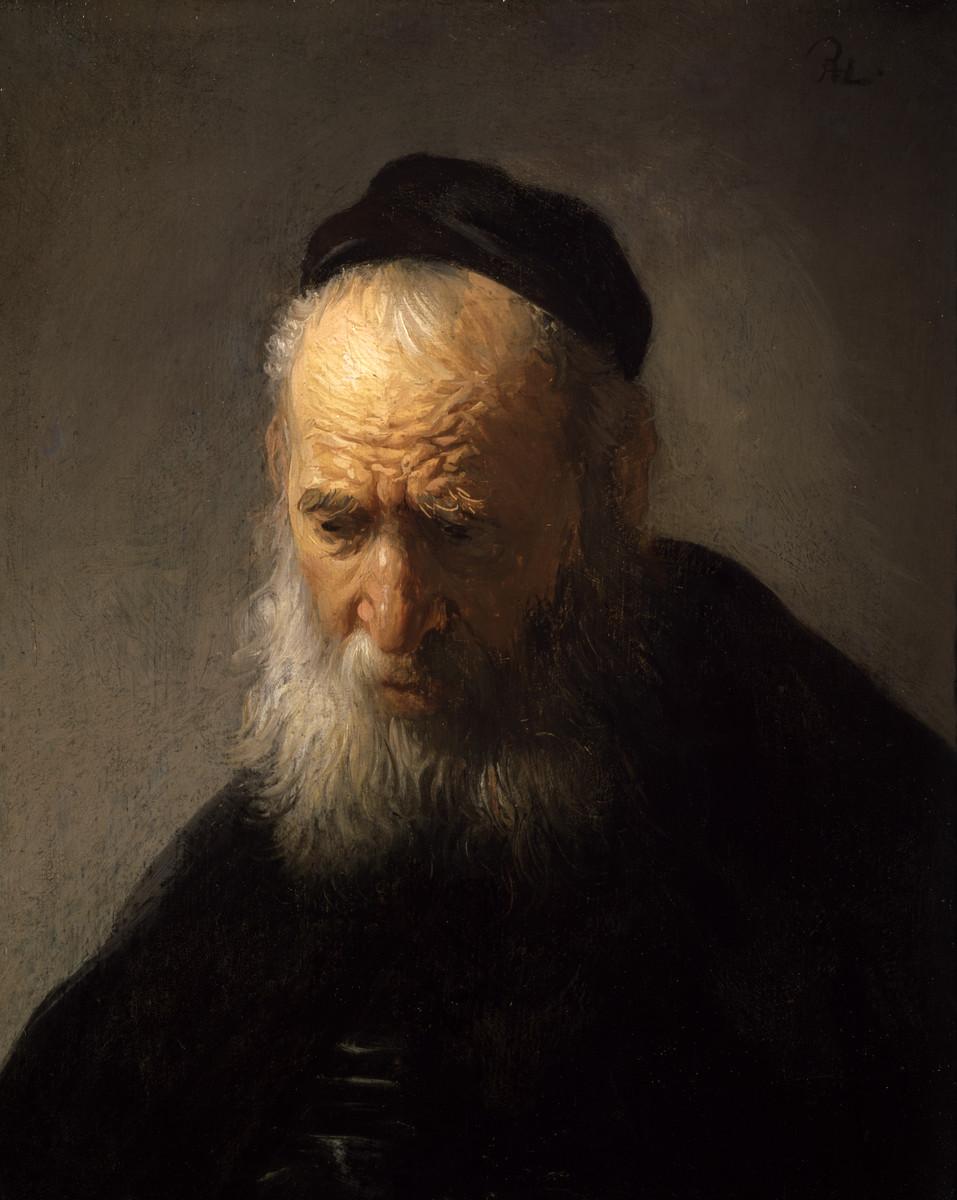

Rembrandt van Rijn, Head of an Old Man in a Cap, around 1630. Oil on panel, 24.3 x 20.3 cm. Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2003 (46-031). Photo: John Glembin

van de Meerendonk: Similarly, for a long time, it was assumed that most of the figures in Rembrandt's portraits were direct family members – an idea that stemmed from, and reinforced, the vision of Rembrandt as a solitary, insular artist. The painting Head of an Old Man in a Cap was for a long time was known as Rembrandt's father, but we know from looking at a known drawn portrait by Rembrandt, that it is not a likeness. Similarly, Jan Lievens’s, Profile Head of an Old Woman (“Rembrandt’s Mother”) was known as Rembrandt’s mother for a long time, but that seems highly unlikely, as she could not have been more than a little over 60 at the time the painting was made.

Jan Lievens, Profile Head of an Old Woman (“Rembrandt’s Mother”), around 1630. Oil on panel, 43.2 x 33.7 cm. Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2005 (48-001). Photo: John Glembin

What is involved in positively identifying a Rembrandt? How does a work move from being attributed to being confirmed?

van de Meerendonk: Every instance is unique and, at times, also relies on technical research, which is an evolving field. Head of an Old Man in a Cap, a signed work, is a good example. It was long accepted as a Rembrandt, then rejected as such and only later re-acknowledged. It was initially rejected in the 1970s when the majority of the members of the Rembrandt Research Project felt that the painting style was too rough for early Rembrandt – revealing the kind of assumptions experts can have about how an artist painted and evolved.

So, it came into Alfred Bader’s Collection in 1979 as Circle of Rembrandt. The re-attribution, in the early 2000s, was largely based on a print showing the same composition with an inscription identifying Rembrandt as the responsible artist, made by his contemporary Jan Gillisz van Vliet. Research about van Vliet and Rembrandt’s relationship was much improved in the late 1990s. Technical examinations of the paper, including watermarks in different impressions, showed Rembrandt and Van Vliet collaborated quite closely in creating prints after his designs, so it became clear Van Vliet would not be mistaken about who created this work. Ideas about how Rembrandt painted have also been adjusted as a result of such re-attributions.

What are some of the biggest ongoing challenges or topics in Rembrandt scholarship?

van de Meerendonk: Developments in technical research are providing increased data, particularly around the material makeup of these paintings, which is exciting. But it does not necessarily make the question of attribution easier because it also raises more questions about methods and collaborations. The interpretation of that data is always going to be in part, subjective. The long-acknowledged world leader in the field of Rembrandt studies, Ernst van de Wetering, recently passed away, so there is now no clear authoritative voice to resolve these more subjective questions. But perhaps this will lead to new directions.

Levine: There is a painting from the AGO’s Collection called Portrait of a Seated Woman with a Handkerchief and we have scientific evidence, relating to Rembrandt’s unique preparatory technique, indicating it was produced by Rembrandt or someone working in his workshop. But it still leaves us with this whole realm of uncertainty. Attribution will always be a combination of technical research and connoisseurship.

Featuring works generously loaned from the Bader Collection at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Painted Presence: Rembrandt and His Peers is on view now on Level 1 at the AGO in the Reuben Wells Leonard Rotunda. For more details, visit AGO.ca