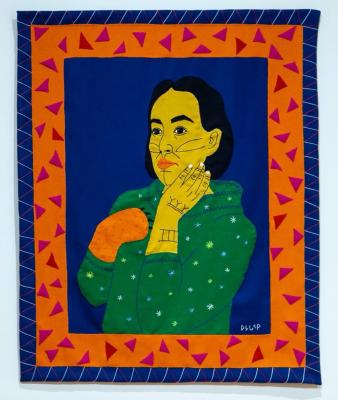

The art of visible mending with Arounna Khounnoraj

The textile artist shares her journey to practicing and teaching visible mending

Image courtesy of the artist.

When you notice a hole in your clothing, what’s your reaction? Embarrassment? Shame? A burning itch to hit the mall and find a replacement?

For Toronto-based textile artist Arounna Khounnoraj, a rip, tear, or hole is the perfect opportunity for creative expression.

Khounnoraj grew up in a family of makers. Her mother became a seamstress after her family moved from Laos to Toronto when she was four. Unable to afford new clothing, her mother handmade all their clothing, and when holes appeared, she mended them.

“[My mother] would fix our clothes because we didn't have the money to buy new clothes,” Khounnoraj recalled. “There was a lot of shame around having clothes that were mended, so my mom would painstakingly fix our clothes and try to make it invisible.”

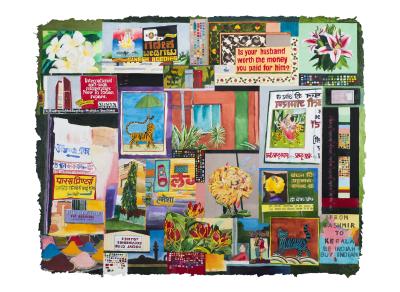

Image courtesy of the artist.

When it came time for Khounnoraj to mend her own family’s clothing, she turned that childhood shame on its head. To honour her family’s beloved items, she chose to repair clothing so that the mend stood out, a practice called visible mending.

“The idea of showing the mend and making it visible felt like a celebration of the hole,” she said. “It was also a way of being self-expressive. Growing up, my mother didn’t have the freedom to be expressive - it was very much about staying within the lines and plugging away.”

Five books and countless workshops later, Khounnoraj has dedicated years to teaching people various crafting techniques, including her upcoming visible mending workshop at the AGO on June 5. In this no-experience-needed workshop, Khounnoraj will teach participants the art of repairing and refreshing beloved clothing items through different stitches and patchwork.

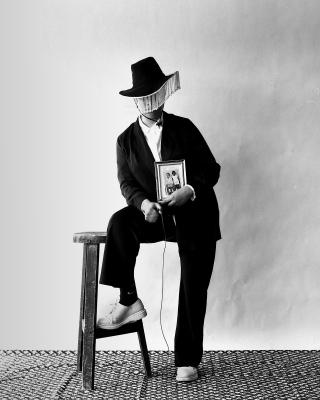

Image courtesy of the artist.

From Khounnoraj’s perspective, visible mending is not a difficult skill to learn. She likens learning how to stitch to learning how to draw straight lines. Alongside learning the practicalities of mending, Khounnoraj hopes participants leave her workshop renewing not only their clothing but also their relationship to it.

“When somebody mends something, they spend an hour or so working on the piece and it makes them more connected to it,” she explained. “I think that’s part of the problem with fast fashion. We’re not connected to [our clothing] and that’s why people are so okay with throwing things out. Mending is not just about fixing clothes; it has a psychological element. It’s like when you were a kid and hurt your knee. When your mom put a band-aid on your knee, it felt better even though you didn’t know why. You fix a hole, and it makes you feel better. There’s a connection to your objects.”

Sustainability wasn’t always consciously at the forefront of Khounnoraj’s work. It was an inadvertent skill she learned from watching her parents trying to make ends meet.

“My parents were makers out of necessity, so, in our practices, we were always trying to use what we had on hand, trying not to create waste,” she recalled. “We know that the clothing industry is now one of the largest pollutants in the world… When you have a sweater with worn elbows and think about throwing it out, it just seems crazy because that sweater still has a lot of life in it.”

Sustainability became a core element of the company and studio Khounnoraj and her husband John Booth opened in 2002. bookhou, a combination of their last names, is dedicated to bringing art into everyday life through natural materials and slow, handmade production. Through bookhou, Khounnoraj sells her making projects and her textile art. Her work in the two fields is interconnected and inspired by patterns in the mundane, such as the streetcar tracks and gardens she passes on the street.

Image courtesy of the artist.

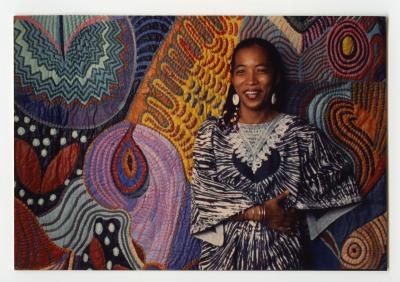

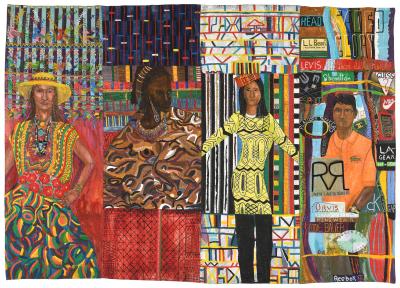

Currently on view at the AGO, the exhibition Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 features the works of women makers and artists, inviting viewers to reconsider what and who is included in European art history. As both a textile artist and a maker, Khounnoraj sees the boundary between making and art as fluid, their definitions dependent on intention.

“One of the most important exhibits I’ve ever seen was The Quilts of Gee’s Bend at the Whitney [Museum of American Art] in 2002,” she said. “They’re a group of Black women from Alabama who make quilts without following the traditions of quilt making. A lot of their work is improvisation, using materials they have on hand such as denim. A collection of the quilts was hung like paintings at the Whitney and the way [these women] used colours and shapes, the quilts looked like abstract paintings. You might have never thought of them as abstract paintings if they weren’t hung in a museum or gallery. When you put something on a bed, it becomes something that is domestic and functional. Hang it on a wall, it becomes seen as artwork.

Image courtesy of the artist.

“I don’t think it’s fair to categorize [making and art] as two different things. It comes down to what the intention is. Does [the maker] want to consider it art? I think people get stuck in the technique of it because if they’re sewing, they associate that with the domestic. When I do a visible mending class, I always tell them that they’re making wearable art. Those stitches are just like brushstrokes on a painting.”

Create wearable art with Khounnoraj at her visible mending workshop on June 5 at the AGO. Tickets for the workshop are on sale here.

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 is co-organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Baltimore Museum of Art. The AGO presentation is on view on Level 2 through July 1. The exhibition is co-curated by Dr. Alexa Greist, AGO Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings and Dr. Andaleeb Banta, BMA Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs.