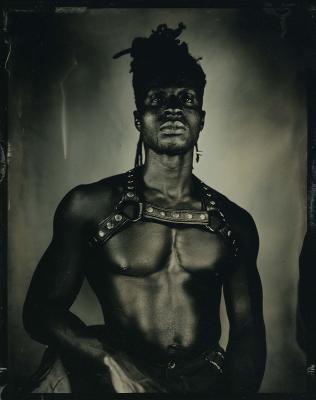

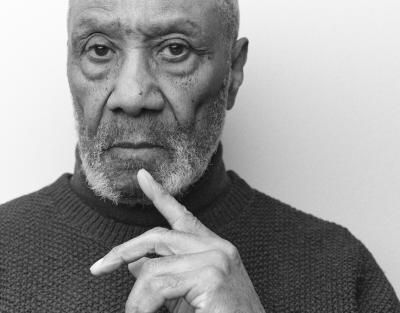

Q&A: Brian Porter, Principal, Two Row Architect

In this new series, we introduce the team behind the Dani Reiss Modern & Contemporary Gallery.

Image courtesy of Two Row Architects.

Just outside Brian Porter's office, at the headquarters of Two Row Architect located on Six Nations of Grand River, there is a tract of virgin forest. It’s where, when seeking visual inspiration and moments of respite, he often goes for walks.

Founded in 1992 by Brian Porter of the Oneida Nation (OnΛyota'a:ka), he’s the principal architect at the 100% Indigenous-owned firm. Recipient of numerous awards and accolades for his approach to social equity and sustainability, he’ll tell you that it’s nothing new - just what Indigenous Peoples have been doing for 30,000 years.

As one of three architects propelling the design of the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery, his vision informs everything from building materials to the location of windows, and Brian continues to lead consultations with Indigenous leaders and communities. In this first installment in a new series highlighting the people whose creativity and passion are making the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery expansion project a reality, we caught up with Brian to learn more about how he came to architecture, his favourite buildings and why he thinks it’s his job to pass around the flashlight.

Foyer: How did you come to a career in architecture?

Brian: I was always interested in fine art and mathematics. My guidance counselors in high school suggested a career in fine art, but I wanted something more collaborative, and architecture seemed to be a good convergence. That and building have always been a part of my life.

My father was the youngest of six brothers and, growing up on the reserve, we spent many weekends renovating someone's house. Each of my uncles had a specialty, and I learned from all of them. Even after I graduated from university, my opinion still didn’t matter much - their cumulative experience was what mattered. For instance, my dad Roger was a good painter and drywall finisher. My uncle Dave was a good welder. My uncles Joe, Walter, Gus, and Albert were good carpenters. Through them, I got a hands-on introduction to the ideas of space, construction, sequencing, and materiality, as well as a certain level of confidence. As a result, I’ve never been self-conscious about building things and have always seen it as a collaborative endeavor. This carried through to my late teen years when I got to help several of my friends build their houses. It was a great experience. And if there was beer and chilli served afterwards, all the better.

Foyer: What was the first thing that you built that you were really proud of?

Brian: One of the first projects I did when I moved back to the reserve from Toronto in the early 1990s, after the birth of my son, was the Emily C. General Elementary School. Its purpose was to amalgamate several smaller one and two room schoolhouses into a facility that could serve a large section of the reserve.

Because I had worked for a year at Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), I was very familiar with their School Space Accommodation Standards which governed new construction. Since the firm I was with at the time knew little about them, they handed the project to me, and I ended up leading the whole thing from start to finish. For the construction stage, the community didn't want to hire a general contractor because they wanted to optimize the local workforce. So instead, we took a construction management approach to the project by working with the community to identify which aspects local trades workers could handle, what we could bid out to Six Nation construction companies, and what specialized trades we needed to go external with. As a result of this process, we were able to get about 80% of the labour done by Six Nations residents which, at the time, was unheard of.

The project also allowed me to incorporate some of the traditional Indigenous values that I had been studying while I was at school - things like directionality and Accepting Mother Earth’s gifts such as utilizing ground source energy to provide heating and cooling load demands. At the time, INAC would not fund air conditioning in its building projects, so it was a sly move to work such systems into the design. By installing a geothermal energy exchanger — which is capable of both heating and cooling — we were able to better meet the community’s needs while still complying with the federal funding criteria. I was very glad that at the ribbon cutting ceremony when the school opened in 1992 that Emily C. General herself was there. She was a former teacher on the reserve who had lost her job because she wouldn't pledge allegiance to the Queen during the required oath of office. She ended up driving a school bus during the later years of her life. She’s a local hero, and I’m proud to have been a part of that building.

Foyer: Beyond your own work, do you have a favourite building?

Brian: Machu Picchu. Perhaps it is a settlement more than a building but there's nothing contemporary that even comes close to its richness and responsiveness to its location. One of the best things I ever did was spend the night at the site. There was an adjacent hotel that only took international reservations, and I made one. This meant that folks arriving by bus couldn’t book it. So, I checked in, waited for the crowds to leave on the last bus, and then had the place largely to myself. It was one of the best days of my life!

Foyer: Your work has received praise for its approach to social equity. As a builder, how do you instill equity into a built form?

Brian: That’s a two-part answer. Firstly, our firm is particularly strong at community engagement. We don’t have a signature style. We try to do projects where the spaces are open to interpretation, and where the built forms can serve a variety of uses and functions. When we can, we allocate generous time at the outset of a project to give ourselves the privilege of hearing local stories and understanding local traditions. Our designs are then very much derived from those shared stories. Equity is about listening first. Secondly, as a firm we have a relatively flat organizational structure that avoids hierarchy. Everyone has to do everything. How we work together is as important as the work we do. There's an analogy I like to use a lot to illustrate how we work. If you have a bunch of people in a dark tunnel, many architects are trained to believe that they hold the lone flashlight to lead everyone out of the darkness. Whereas we're more about giving everybody a flashlight so that we can all find our way out together.

Foyer: Questions about sustainability, accessibility and equity have put immense pressure on architecture to be about more than just building spaces. Do you think architecture is becoming more or less creative as a result of that?

Brian: What I really like about working in 2023 is how various disciplines, including Indigenous designers, are getting a seat at the table early on with the architects. As such, projects are being propelled by multidisciplinary teams of creatives working together. Gone are the days of designs being dropped in by international architects that have little connection to the community. Now we’re seeing everyone from landscape architects to arborists to civil engineers, etc. making more meaningful contributions. I think that design solutions are getting richer for it.

Canadian architecture, as a rule, is getting more sustainable and more integrated which is great. It's finally cutting its coat strings from its European precedents and developing solutions which are more inherently Canadian. But what’s frustrating for me personally is that many of the sustainability standards that the industry is just finally now embracing - LEED Accreditation, WELL Certification, the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and all that stuff, aren’t new. As Indigenous Peoples, we've been practicing them for 30,000 years. I realize that our climate is tough, but Canada needs to be an energy leader.

Foyer: Where do you go for visual inspiration?

Brian: I like to take walks. Our office complex and the nearby homestead where I grew up, both back onto virgin forest, which is often where I’ll go. I’m more of a traveller than a vacationer. I’ve seen a lot of the world, and definitely being exposed to far-flung places matters a lot. But I would still put the training that I got with my dad and uncles above all that.

Stay tuned for more exciting insights and updates regarding the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery.