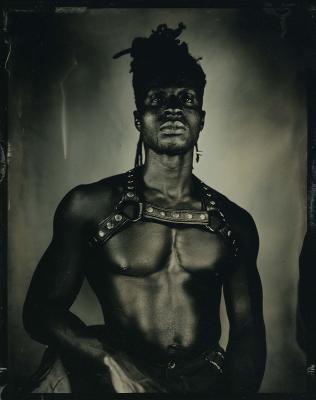

Q&A with Don Schmitt, Principal, Diamond Schmitt Architects

In this continuing series, we introduce the team behind the Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery.

Image courtesy Diamond Schmitt Architects. Photo Credit: Jim Ryce

From New York to New Brunswick, and in more than 50 cities around the world, Diamond Schmitt Architects' elegant, purpose-driven, highly sustainable designs of cultural, academic, research, healthcare, and civic spaces, have transformed our lines of sight. And yet, when asked, to what does he credit these many achievements, Don Schmitt, Principal, Diamond Schmitt Architects, doesn't point to his eyes. But his ears. For Don Schmitt, superior design stems from good listening.

One of three architects propelling the design of the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery, Don comes to the project with an intimate knowledge of the Toronto landscape – and a decades-long connection to the AGO. The Founding Chair of the Public Art Commission for the City of Toronto, his commitment to green, innovative design, lives in the building’s passive house design standards, net-zero carbon operations and its smooth integration into the existing AGO building.

In this third installment of our ongoing series highlighting the people whose creativity and passion are making the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery expansion project a reality, we spoke with Don about how he came to the field, his inspirations and how the solution to any architectural problem, is likely in a book.

Foyer: How did you come to architecture?

Donald: As a teenager, I read a book called The Master Builders by Peter Blake. It was a combined biography about the three great architects of the 20th century: Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. And I thought, wow, what fantastic lives, these three people led. It really captured my attention and made me excited about what one might do with one's life.

What was interesting about that book was how it went beyond design to talk about practicing architecture as a way of life. And through various twists and turns, I have managed to realize that fact. Architecture is a way of life. It provides an entrée into worlds that I might otherwise not have seen or known. When designing a ballet school for instance, you get to spend years getting to understand the lives of dancers; building for Sick Kids Hospital, you get to learn about the world of scientific research.

Working for the Art Gallery of Ontario has been so revealing – it is an institution that I have known and loved for most of my adult life, but the work has given me a uniquely back-of-house view, a behind-the-scenes education. It’s allowed me to see the collective efforts of so many people, to understand how it ticks. That was the revelation Peter Blake wrote about in his book and it is something I have found in my career to be true.

What was the first thing that you built that you were proud of?

The first things that I was proud of, I built in my 20s. I was scared out of my mind. One was a medical clinic near Arvida, the Alcan company town, north of Quebec City. It was a 30,000 square foot freestanding building. I was able to deliver a building that was focused on health and wellness that I really loved. The next building I designed after that, still in my 20s, was the central YMCA here in Toronto. I was surprised, and gratified, that people, other architects who I knew really admired it as well. Those were exciting moments.

What is the most satisfying part of the design process for you?

Good architecture is about being a good listener. Listening, not just to the quantitative needs – seven of these, three of that, a roof, a window – but the more sensitive, qualitative goals. They are the important bits, the things that can allow a building to transcend its practical program, its programmatic requirements. It can give you the clues to making a more inspired environment.

Being a good problem solver comes second. Every project has challenges. The sum of the solutions is what makes a building great. So, problem solving, I enjoy a lot. Being a good listener, I hope I do well. What satisfies – what gets you to an inspired outcome – is when you can fulfill the functional requirements, find solutions to all the inevitable problems and meet your client's vision.

In 2019, when you received the Order of Canada, they said it was in recognition for your work to rehabilitate iconic heritage buildings and for your work in sustainable design. How feasible is it to make iconic buildings sustainable? Is it one ideal or two?

It's an interesting question. The bit about rehabilitating heritage property is a reference to the renovation work I did on the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. It's a great public cultural institution on Confederation Square looking straight at Parliament and the Peace Tower. Before we started it was a million square feet of concrete, that people loved and hated equally – extremely beautiful brutalism, but inaccessible, with all sorts of blind spots. The renovation we did made it a building that people wanted to be in – reorienting it, reconnecting it to the city and landscape. The goal was to make it more welcoming, more accessible, more visible, full of natural light, and transform it into a sort of community living room that can be used all day long. To open the space was the goal of the renovation and restoration.

But connected to that, is sustainability. Traditionally, in the last 50 years in our society, when a building has had a problem, we've torn it down. And, in the case of the National Arts Centre, that would have sent a million square feet of material to landfill. That is not a sustainable strategy at all. Finding ways to re-energize older buildings, to find more appropriate uses for them – that is the first step to sustainability. But then beyond that, it is understanding how you make buildings perform better.

From an environmental perspective, 20 years ago, we weren't particularly good at it. There's been a sort of exponential growth of knowledge and understanding and information in the last couple of decades, that allows us to make buildings which are require almost no energy input. Like little energy plants unto themselves, they can be constructed to sit so lightly on the earth, or at least operated, almost free of carbon impact. And that's a huge accomplishment. The AGO addition, the Dani Reiss Modern & Contemporary Gallery is a good example – seeking as it does to be net zero carbon from an operational perspective. It'll be one of the first major cultural facilities that has been able to do that. That interest in renovation, rehabilitation, revitalization and sustainability, they're joined – stemming all from the same idea that what we need are more environmentally responsible and socially relevant buildings.

Do you have a favourite building?

One of the buildings that inspired me to go into architecture was Massey College at the University of Toronto. I wasn't born in Toronto, but I grew up here. I loved Massey College then and I still love it. Such a great building by the fabulous architect Ron Thom. The list is long, but I've always loved the AGO’s Walker Court – how it's remained a kind of centerpiece throughout the AGO’s many iterations. There's something about that calm at the center of the gallery that is so representative of a public institution – it's allowed to have no specific use. It's not a gallery space. It's not an entry. And yet it has many lives. It’s a flexible crossroads at the center.

Finally, where do you go for visual inspiration?

I have a weakness for books. I have hundreds and hundreds of books about art and architecture. If I'm at a loss on a project, just browsing through books begins to get me going again.

I also travel. I'm constantly inspired by seeing things – be it a landscape or a building. One of the most magnificent buildings I've ever been is Hospital Sant Pau in Barcelona. It’s a functioning hospital, that was built at the turn of the century. It astonishes you – reminds you that this is what hospitals can be, what hospitals are. One of the things I did early in my career was take eight months and just travel around South America. I thought I’d be too influenced by what I had read, to see Europe so young. At the time, I knew nothing about South America, and I thought, if I go there, I'll have to make up my own mind about what I'm seeing. And that was a revelation of the value of travel, looking, sketching, walking, measuring and understanding. The incredibly sophisticated built fabric that I saw there of both Indigenous and Spanish colonial spaces, the modernity of Brazil, of Brasilia – all of it was important to me. Books are, I suppose, just another form of travel, albeit on the printed page.

Stay tuned for more exciting insights and updates as construction continues the Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery – an expansion designed to increase space for the AGO’s collection of modern and contemporary art, set to open in 2027.