Ian Kamau’s philosophy

Multi-disciplinary artist Ian Kamau reflects on his hip-hop beginnings in Toronto.

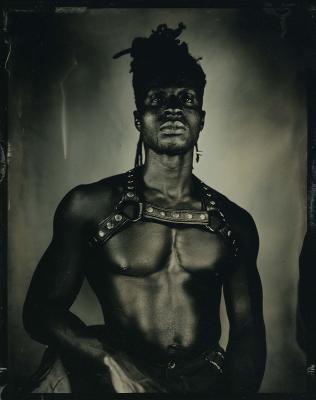

Ian Kamau. Photo by Roya DelSol.

In the 50 years since its creation, hip-hop has grown to be the highest-grossing genre in the North American music industry. Its massive international impact on art and culture is immeasurable, and its undeniable influence is present in everything from fashion to philosophy.

While New York City’s long and storied history as the birthplace of hip-hop is frequently documented, the inception story of hip-hop in Canada is rarely told. Long before the Drake era, hip-hop rooted and blossomed here in Canada – especially in Toronto – thanks to the passionate contributions of local MCs, DJs, B-boys and girls, graffiti writers, promoters and fans.

Ian Kamau is an essential thread in the fabric of Canadian hip-hop. Cutting his teeth as a young MC in the mid-90s, his affinity for music, film and performance has evolved into a thriving career as a multidisciplinary artist. As the son of two pioneering Black Canadian filmmakers (Roger McTair and Claire Prieto), a career in the arts was modelled for Kamau at a young age. After being introduced to hip-hop by his cousin Roger Mooking at 10, his teenage years were spent writing rhymes and carving a path for himself in the community as an artist. Among an array of other accomplishments, he would go on to tour Europe with platinum-selling musician K-Os (2003/2004), co-found Nia Centre for the Arts (2009), create the beloved 2011 LP One Day Soon, direct the short film We Went Out (2022) documenting Toronto hip-hop history, and stage an introspective one-man show entitled Loss (2023).

As hip-hop’s birthday approaches this August, Kamau spoke to Foyer about the many complexities of Toronto hip-hop, his artistic philosophy, and some of his most notable creations.

Foyer: Can you share your first personal memory of hip-hop? How did that moment build into you eventually becoming an MC?

Kamau: In 1988, two years after my parents separated, my father gave me two dubbed cassette tapes: Run DMC, Tougher than Leather and DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, He’s the DJ I’m the Rapper. I didn’t understand Tougher Than Leather, but I loved He’s the DJ I’m the Rapper. I was eight.

In the 90s, the culture was passed from person to person mostly informally. It was made and influenced largely by first and second-generation Caribbean kids in New York who had roots in Jamaica (Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa), Barbados (Grandmaster Flash), Puerto Rico (Crazy Legs), Trinidad (Fresh Kid Ice). It was an evolution of Caribbean musical and DJ culture and an amalgamation of different cultures, both American and immigrant from places like where my family is from, Trinidad.

When I was about ten years old, my parents went to Banff for a residency. I stayed with my Aunt Gemma and Uncle Alloy in Edmonton while my parents were away. My cousin Roger (Mooking), the youngest of their three children, was just a little older than me, so I spent most of my time with him in the basement, where his room and the den were. He’d play me dubbed VHS tapes of Rap City and X-Tendamix with Master T, Soul in the City with Michael Williams and live performances on Arsenio Hall. He introduced me to A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, X-Clan, and Pharcyde. He was my first real teacher about the culture. He was a teenager.

Roger moved to Toronto and lived with my mom and I when he was nineteen. After doing music with a rap group called Maximum Definitive, he joined a group called Bass is Base. He took me to his studio sessions. He kept a book of rhymes. My father is a writer, so I had been writing poetry for a while, but after my cousin moved in, I started keeping a book of rhymes myself.

When my cousin moved out, he lived in a basement apartment with Jonathan Ramos, a young promoter who had just started a promotion company called REMG. They got me into my first concert, A Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul, at the Palladium, one of Jonathan’s first promo gigs. I met Posdnuos from De La backstage. I was going to Oakwood Collegiate at the time and met friends who were also into hip-hop and who continue to be my good friends to this day: Danilo McCallum, Paul Sackichand, and Miaskye Sagara.

We would go to everything we could find that was hip hop-related, 416 Graffiti Expo (also promoted by Jonathan Ramos beside the Bamboo and later at the parking lot at Queen and Portland), events hosted by Fresh Arts (an arts program that helped many of the artists we looked up to put out their first music), and Planet Marz (a small hip hop show organized by local artists). We watched Toronto artists like Kardinal, Jully Black, Marvel, Tara Chase, Mathematik, and Saukrates come up, release their first vinyl, albums, and videos. We’d go to college Radio at CIUT and CKLN to freestyle and to try to get our stuff on the radio.

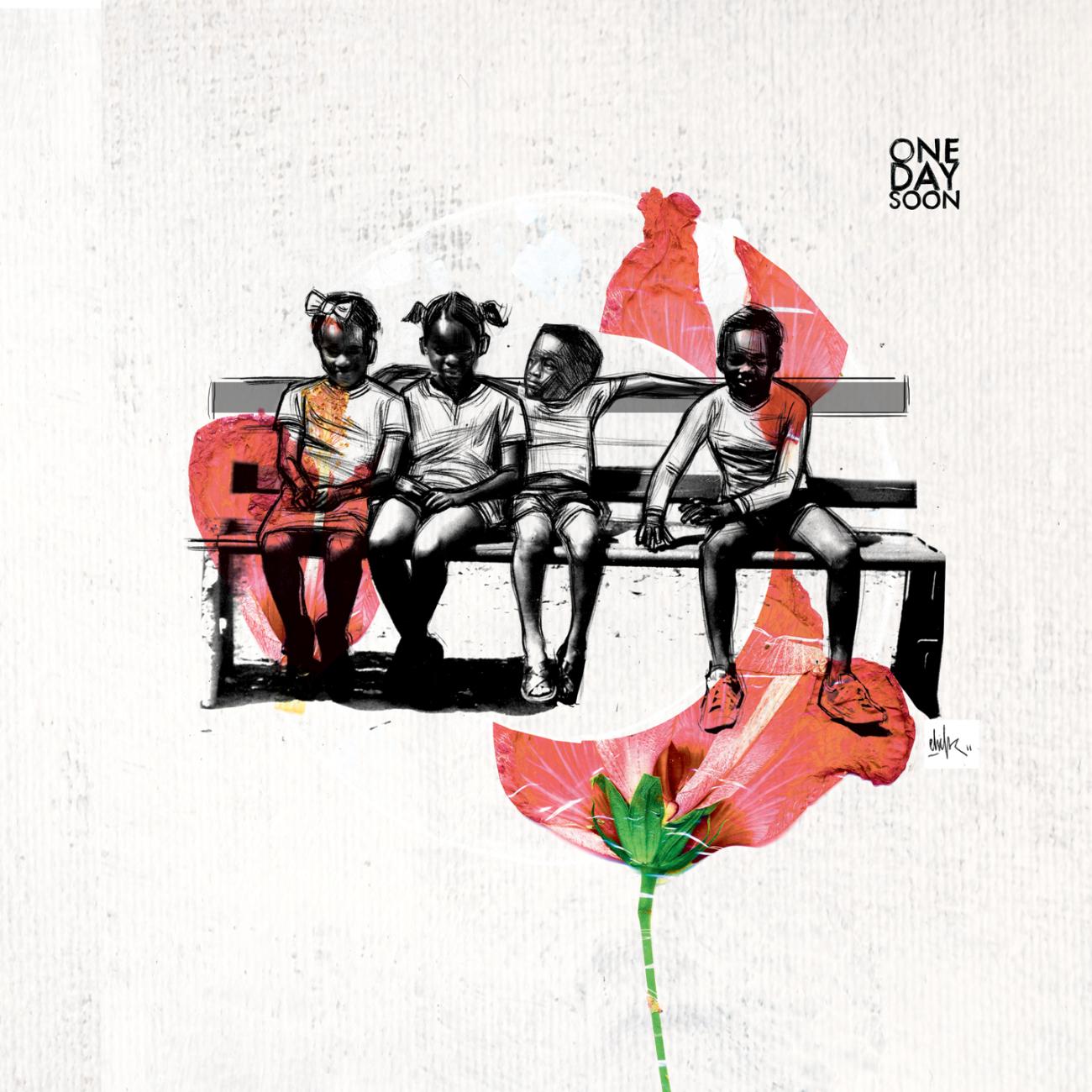

One Day Soon (2011). Image courtesy of Ian Kamau

In 2011, you released your full-length LP One Day Soon, and embarked on a tour across Africa, including dates throughout South Africa, Kenya and Ethiopia. How did that experience help shape you as an artist? What were some of the major learnings you were left with?

I toured through Johannesburg, Pretoria, Capetown, Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, and Grahamstown in South Africa. I performed in Nairobi, Kenya, Harare, Zimbabwe, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Windhoek Namibia, Kigali, Rwanda.

I was not feeling good about Toronto at the time and was happy to leave. I spent five and a half months touring in Africa, but also just living and being with a different group of people. The experience gave me life after what felt like the end of something in Toronto. I felt let down in my personal life, in my relationships, let down by Toronto, limited by Canada and its lack of care. There was no community as far as I was concerned, so I was very happy to be able to live as an artist in places that I had dreamed of going. I left understanding that you should go where you are wanted and not be bound to where you’re from, that to be an artist also means to constantly explore possibilities.

I did more than thirty shows in 2012 in different cities on the continent and went back the following year to do more.

Using a mix of original and archival footage, your 2022 autobiographical short film We Went Out intimately documents Toronto’s hip-hop scene in the 90s through the lens of a close-knit group of friends. What would you like people to know/understand about the early days of Toronto hip-hop?

I don’t really want anyone to know anything. I think those that know, know what this is about. There are thousands, maybe millions of stories like this in Toronto from different neighbourhoods, different high schools, different corners, and with different friend groups. Toronto hip-hop was a tight community of creative people that made things because they loved the culture and wanted to contribute. I think if we are to understand ourselves we should tell our own stories, and focus on the people that understand already.

I made We Went Out because Rosina Kazi called me and asked that I make it. She was curating at Luminato at the time. I wanted to document my closest group of friends and our story from our perspective. I wanted to tell a story of our city that isn’t normally told. We Went Out is about us, Toronto, hip hop, kids who live in neighbourhoods with their moms, and the beautiful things that come out of in-between spaces.

Given Toronto’s prominence in today’s international hip-hop industry, why do you think the inception story and early narrative of Toronto hip-hop remain so under-documented?

Toronto is not good at valuing its artists or its own story. I think Toronto has always had an insecurity complex. Toronto has always seen itself as the little cousin of New York, Los Angeles, or Atlanta. We are not from those places, we’re from Toronto. It has taken this long, and lots of investment from the States, for Toronto to start to feel proud of itself. I think the generation that Drake has led feels differently about the city because a few artists came out being very proud about loving the city. I hope that pride can translate to more development, more infrastructure, and better artist development that comes from the city itself, I’d love to be a part of that. I hope more everyday people tell stories about Toronto and tell them well, even if it’s just with their cell phone camera. I loved that much of the Wolfgang Tillmans show was mounted with scotch tape, I love that the Basquiat show had reflections from local artists with their pictures, and I love that Jabari Elliot paints on anything available. I think we should just work and worry less about the polish; let’s just use our talent and what we have to tell the fucking story.

This year, you debuted a one-man show entitled Loss. Apart from the obvious, what does the show explore? After making music and films, how would you describe your first experience writing and performing in a theatre space?

After losing a relationship, after One Day Soon, and after getting fired from Nia Centre for the Arts, an organization I co-founded, I experienced a winter of deep sadness. I had lost these things but also lost my faith in community, and my entire worldview fell apart. I didn’t know if I would be an artist again or if art meant anything. I had to start from scratch and build myself up again. Part of the process of doing that involved exploring my psychology, my misconceptions, my assumptions, and my family. To be honest I don’t like to talk about Loss because I just wanted people to come and see it, all the explaining does it no justice, it’s an experience, not an academic paper, it should be experienced.

I don’t particularly care about theatre, or “the theatre space,” and I don’t consider Loss to be theatre. I don’t know what it is exactly, but it’s certainly not a play. I’ll leave the plays to the theatre people. I consider myself an artist without a particular genre, I’ve been called multi-disciplinary a lot recently, but I really don’t have a desire for any name. I’m an artist. I make art. I love music, film, writing, and performance art (when it’s good). I’ve seen dance and experimental work, and I read, walk, and experience the world. I think art should do that, and I think the concern about genre is mostly for marketing and industry folks who are focused on selling things. I’m an artist, a writer and a designer. I’m mostly concerned about making and designing things.

The short answer is Loss is about working through a sadness that many of us feel. It is the loss of place, loss of community, loss of relationships, loss of people, loss of identity, loss of youth, loss of innocence. It is unfinished and might never be finished, but it’s more about the process more than a final thing.

Stay tuned for more Foyer stories like this one documenting hip-hop’s 50th anniversary from Toronto and beyond.