Postcard from Kingston

Travel Jamaica's capital with O’Neil Lawrence, Chief Curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica.

National Gallery of Jamaica, Front of Building. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

In 1985, Kingston-born dancehall DJ Brigadier Jerry released the song “Jamaica Jamaica”. A nostalgic tune with a driving rhythm, his lyrics (expressed in Jamaican patwah) take listeners on a celebratory homeland tour, making stops in Jamaican towns like Ocho Rios and Spanish Town and venturing into parishes like St. Catherine, Hanover and Portland. Nestled along the southeastern coast of the island is Kingston, the nation’s capital. As Jamaica’s most populous city, the buzzing metropolis echoes the Jamaican national motto established in 1962, “Out of Many, One People" — a nod to post-colonial independence and rich cultural diversity. Kingston is a centralizing hub for the country’s foremost financial, governmental and cultural institutions, including the National Gallery of Jamaica (NGJ). Deemed the “custodian of Jamaica's national art” for nearly five decades, the NGJ is the oldest and largest public art museum in the English-speaking Caribbean. Its collection features early, modern and contemporary art made by artists of Jamaican and Caribbean ancestry with sites both in Kingston and Montego Bay.

To broaden our understanding of the arts rooted in Kingston and Jamaican culture, we tapped O’Neil Lawrence, artist, writer, researcher and Chief Curator at the NGJ.

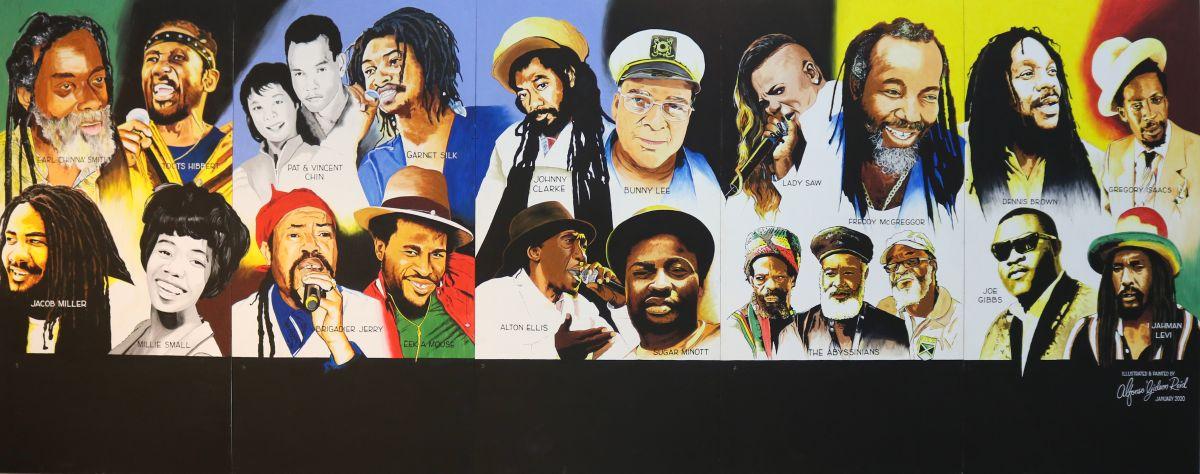

Jamaica Jamaica! Exhibition, Mural by Alfonso ‘Gideon’ Reid. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

AGOinsider: Jamaica is known around the world for its musical contributions, as highlighted in the Jamaica Jamaica! exhibition on view at the NGJ. For those not as familiar, how would you begin to describe the many contributions made by visual artists from Jamaica?

Lawrence: In addition to its focus on the musical heritage of our island, Jamaica Jamaica! also highlights the way all the arts, performing and visual, are intertwined within our history. From murals, posters and record covers to paintings and sculptures, visual artists have inspired, supported and responded to the works of our musicians. What may be surprising to those unfamiliar with Jamaica’s visual arts tradition is the significant contribution that visual artists have played in nation-building. During the pre-independence period, visual artists actively represented the goals of the nationalist movement by challenging the reductive images of people of colour seen in colonial-era imagery. The visual arts played a pivotal role in the establishment of our identity as independent people in an independent country leading up to and after our independence from Britain in 1962.

AGOinsider: Over the course of your career as a curator and artist, what notable shifts have you observed in art and visual culture made in Kingston or by artists originating from the city?

Lawrence: I wouldn’t necessarily characterize this as a “shift” but more of a cyclic occurrence and that is the resurgence of artist-led initiatives in response to either a crisis – like the pandemic – or a lack of opportunities. These have ranged from the Western Jamaica Society of Fine Arts, a decade’s old organization formed to promote and encourage fine arts in Western Jamaica to Resume the Struggle, one of the newest initiatives curating exhibitions for young and emerging artists. The dependence on entities like the National Gallery to be the main platform for significant exhibitions no longer exists and this has made the artistic ecosystem in Jamaica much more diverse and exciting.

Foyer: What would you say is missing from conversations about or explorations of Jamaican art, and even more broadly, Caribbean art?

Lawrence: The rich conversations around Jamaican and Caribbean art have been ongoing and expanding for some time, so it’s difficult to pinpoint something that is “missing.” What I do think needs greater focus is the movement away from considering Caribbean art as peripheral to Western art historical narratives. While useful and instructive, the origin of an artist should not become a limitation to where and how these artists are considered in these conversations.

Foyer: What do you love most about Kingston? What are some of the challenges?

Lawrence: I sometimes view Kingston from the lens of an outsider despite being born here; I grew up in the city of Montego Bay. Kingston, like my home city, has its own unique energy. By virtue of its much larger size and more diverse opportunities, it draws a similarly diverse set of people from all over the island. That combination of people with different backgrounds makes the creative potential in the visual and performing arts limitless. The challenges of course are finding enough opportunities and platforms for all that potential to be realized.

Foyer: What are you looking forward to sharing with audiences through NGJ’s upcoming exhibitions and programming? Can you tell us about the Kingston Biennial: Pressure exhibition?

Lawrence: Kingston Biennial: Pressure has been long anticipated by our audiences both locally and internationally having been rescheduled due to the pandemic. The exhibition’s lead curator David Scott put it best when he said “[W]hat is instructive about the Jamaican experience and the idiom of pressure is that it has always had a generative and dissenting quality about it.” As we’ve been working on this exhibition, the work of several artists has transformed as the world has because of COVID-19. The “pressure” that we’ve all experienced has been a fertile ground for new ideas and expressions so I’m particularly excited for the world to see just how these Jamaican artists have transformed and responded to this new pressure.

The AGO invited Lawrence to interview Jamaican-born contemporary artist Leasho Johnson whose work is featured in the exhibition Fragments of Epic Memory – watch their conversation here. Lawrence and Johnson are also featured in the exhibition’s catalogue – get your copy at shopAGO.