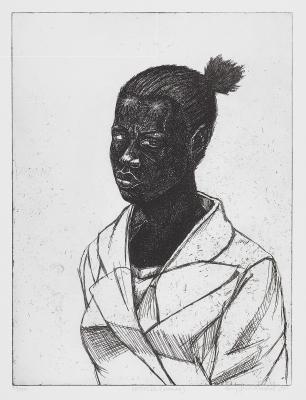

Postcard from Kinngait

Kinngait Studios in Nunavut has been at the forefront of contemporary Inuit art for over 60 years.

image courtesy of West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative.

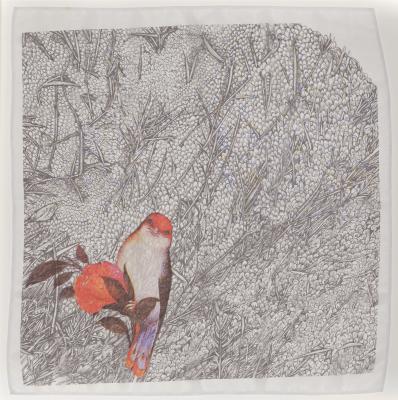

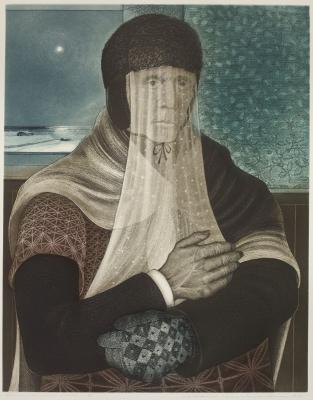

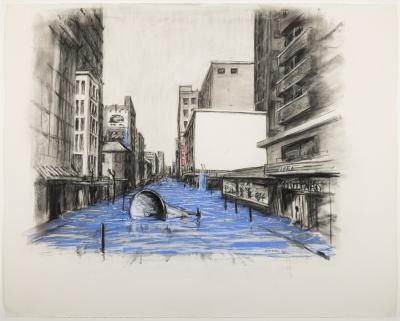

Five successive generations of acclaimed Inuit artists have brought their work to life at Kinngait Studios, in Kinngait, Nunavut, some 2,292 kilometres north of Toronto. Among them is Shuvinai Ashoona, a third-generation Inuk artist based in Kinngait. A major force in the emergence of its contemporary drawing practice, Ashoona works daily at Kinngait Studios. In her recent works, previously on view in the AGO exhibition Shuvinai Ashoona: Beyond the Visible, she merges ink, graphite and colour pencil to create large-scale works in both vertical and horizontal formats. Measuring an astonishing 268 centimetres wide, the recent acquisition Curiosity (2020) gives viewers a fanciful bird’s-eye-view of her hometown, including buildings and roads, a portrait of an Inuk family, a walrus, several seals and the curious tentacles of seven giant pastel monsters.

To better understand Ashoona’s work and the prodigious legacy of the studios, we caught up with William Huffman of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative.

Foyer: Kinngait is located on the southwest coast of Baffin Island. Can you describe the landscape for us?

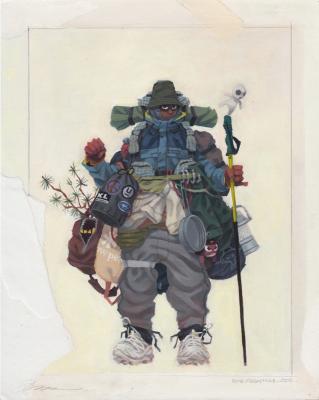

Huffman: The namesake of the place is a range of mountains, or larger hills really, located in the western part of the municipality. You can imagine, even a modestly-sized mountain would be a profound geographic feature in a place that is largely flat tundra. The other Inuktitut name used is Sikusiilaq, which refers to the nearby ocean waters that are often ice-free, even during the coldest winter months. Opposite the mountains is the Hudson Strait, where more than occasionally, you’ll catch the sight of an iceberg. The personality of Kinngait changes dramatically from the winter to the summer months; there aren’t really in-between seasons like we have in the South. Snow starts in October and can be substantial, even in June. Activities throughout the year happen both on land and sea, for hunting and recreation, and of course those narratives have always been important themes within the artwork created in the region. That one of the oldest and most prolific fine art studios in the world exists and thrives in this tiny, remote, Canadian Arctic community of 1,400 residents is remarkable.

Foyer: Kinngait Studio is operated by the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative. Why has the co-operative model been so successful?

Huffman: For the last 60-ish years, the co-operative has been at the centre of artmaking in Kinngait, providing space and means to hundreds of artists over its lifetime. That itself is an extraordinary and expensive thing! When you account for the fact that the place is predominantly fly-in, and all the equipment and supplies used by the artists are flown in, every piece of paper, or pencil, all of it must come from the South. It’s the community ownership of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative that has fostered success. It’s governed by an all-Inuit Board of Directors, and practically all Kinngait adults are in fact shareholders, which means that at the end of each year, profits are distributed back to the community in the form of annual dividends. And in addition to the operation of the studios, the organization also maintains a local retail grocery and hardware store, a restaurant, a few rental properties and manages various utility contracts. It’s a really sophisticated business model and an unique social enterprise, and something in which the community, particularly our member artists, have a deep sense of pride and respect. It’s truly their organization. The recipe for success has been the community’s sustained involvement in decision-making, its clear vision and generally progressive leadership.

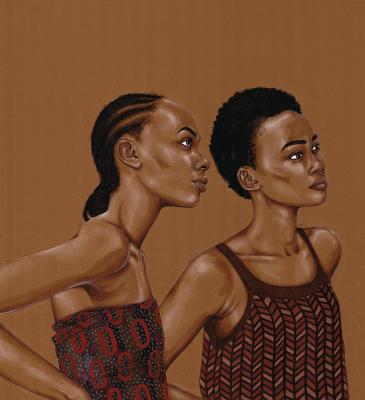

image courtesy of West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative.

Foyer: How many artists are members of the studio at present? Is it operational 24/7?

Huffman: We probably have about 100 artist-members working in drawing and sculpture and of course there are also the printmakers, who work with artists to produce print editions. Some artists do work in the studios daily, alongside the printmakers, who are very disciplined, working a nine-to-five shift, five days a week. The sculptors who work in carved stone, all work from home and largely out-of-doors, because the process creates clouds of quite toxic dust. So it’s more common for us to see the finished work from the sculptors, whereas we often get to see works in process in drawing and printmaking. In any case, the studio is available and often the decision to work onsite or, say, at home, depends on the scale and ambition of the project; quite simply, bigger drawings need more surface space, and the studio was created to accommodate that. The most important advantage to working at the studio is the peer-to-peer exchange, the opportunity for the artists to see and talk about each other’s work, and the Studio has a full-time Arts Manager who provides professional development feedback, when needed.

Foyer: Can you describe the atmosphere at the studio? Is it one of open collaboration or intensive study or both?

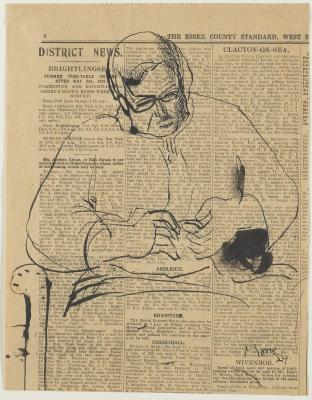

Huffman: There is a high degree of collaboration along with, what I’d characterize as, ongoing learning. Something that surprises most people is that none of our member-artists have studied in a traditional southern academic context; basically none have attended art school, as we understand that to be. From generation to generation, artists learned to do what they do, by watching others, and their practice develops over time by doing. Often when I talk to artists about making art, they will talk very powerfully of watching a mother, father, aunt, uncle, respected friend, draw or carve stone, and that experience became the impetus and encouragement. I’ve been at Kinngait Studios when a young person, high-school aged, will visit, and ask for some supplies to start making art, and that was because someone close got them excited about the possibility of becoming an artist. I’ve also had the distinct privilege of seeing the very first works of art a new artist creates, where there is a spark, many are terrific. But then you follow the development of their aesthetic and visual language over time, and there’s that ‘A-ha!’ moment when it all comes together. And that’s the power of mentorship, intergenerational exchange and the support of peers. From the beginning that was one of the expressed functions of Kinngait Studios, an environment where that interchange, in all its forms, can happen.

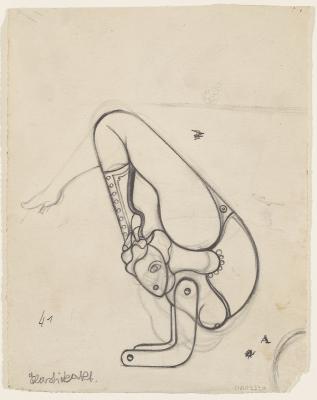

image courtesy of West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative.

Foyer: Although the Studio has existed since the late 1950s, Shuvinai Ashoona has been credited with the resurgence of the contemporary drawing practice. Can you tell us more about that?

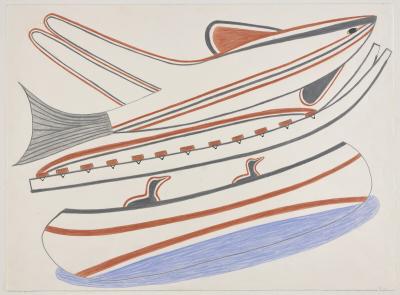

Huffman: Interestingly, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative drawing program was initially created to inform the printing program, with the drawings then translated into lithography, etching or stonecut editions. So, it’s a relatively recent development that drawings were even available for sale, let alone of interest to collectors. Since that shift, Shuvinai has been one of those artists whose drawing practice has exceeded her prints in importance and renown. In fact, her imagery is some of the most recognizable and unique currently being produced at Kinngait Studios. Although she has, and continues, to explore traditional subject matter, the work that has really garnered international attention is the more fantastical and surreal, or how she can adapt that traditional subject matter in a very distinctive way. Her process is also very physical, she’s often laying on the paper, quite close up to the surface, and in that way, her compositions can be extremely detailed. I think how she works is one of the reasons that drawing is a compatible medium for her. Also from a pragmatic point of view, you can do things in the drawn medium that simply isn’t possible in printmaking, scale for instance — drawings can be much, much larger — and that is one of Shuvinai’s hallmark approaches: big drawings. In many ways, Shuvinai has been responsible in fostering new or renewed interest in the drawing program.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/NG-Wn812QHM.jpg?itok=48gLXEtk","video_url":"https://youtu.be/NG-Wn812QHM","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0,"title_format":"@provider | @title","title_fallback":true},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

Foyer: In 2018, the Studio was relocated to the brand new Kenojuak Cultural Centre and Print Shop. Can you describe the centre? What were the design considerations that went into it?

Huffman: I never thought that I’d know so much about architecture and building codes in the Arctic! In the months and weeks leading up to the public opening of the venue, I got involved in all kinds of fun business, like heating, ventilation, alarm and telephone systems. I even found myself, more than once, in the crawlspace under the centre, rooting around for plumbing connections. I remember there was a moment when a contractor needed a specific computer connector, and no one, absolutely no one, in Kinngait had such a thing. I played on the goodwill of the site engineer to get the construction company to use its private plane to fly one up from Iqaluit. Boy, that little connector got some five-star service. Much of what you can build in the Arctic is dictated by location and environment, and everything is much more complicated and wildly expensive. This Kenojuak Cultural Centre is particularly extraordinary because of those challenges.

The design was intended to be light and warm, the ceiling surfaces and other structural details use wood and there are lots of windows. Both those elements can be in short supply when it comes to architecture in the Arctic. There were a few guiding principles embedded in the design, but for me the important one was that the studio portion of the Kenojuak Cultural Centre be state-of-the-art, somewhere anything was possible, and where any artist would feel comfortable. And it was palpable when member-artists first began working in the space, how much they enjoyed being there. With a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape from any part of the building, loads of improved equipment, along with other new technology and amenities, it was more than just an improvement of the studio space– it’s now a site for limitless creative potential.