Ojo Agi on the power of images and brown paper

"What does it mean to represent a Black figure in harmony with their environment?”

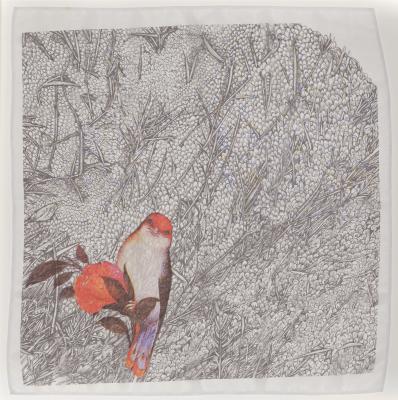

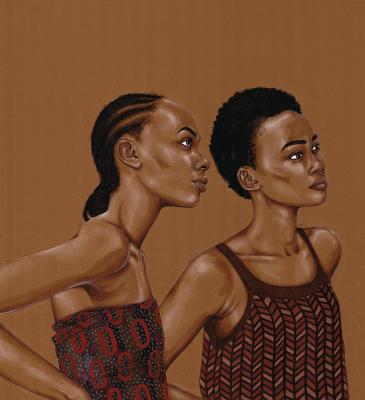

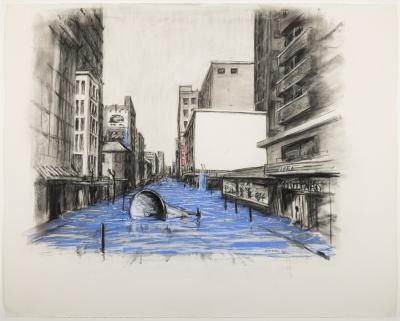

Ojo Agi, Departures Arrivals, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. © Ojo Agi.

Drawing has always come naturally to Ojo Agi. “I have been drawing for as long as I can hold a pencil,” she says. “For me, drawing is like writing. It is a form of communication. I enjoy the act of mark-making, creating something from nothing, and materializing my inner world. Oftentimes, I draw and write together in a visual journal.”

You’ll often lock eyes with a lone figure in one of her portraits, tenderly drawn with realistic details. Her drawings, while simple, place Blackness in all its shades at the forefront and over the past few years, the Toronto-based illustrator and academic has developed a style all her own.

For this entry in our series on illustration, Agi opened up to Foyer about how she came to drawing, why she works specifically on brown paper, and the power of images.

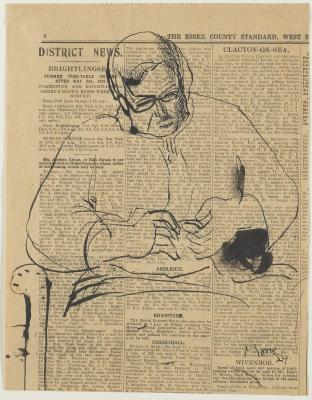

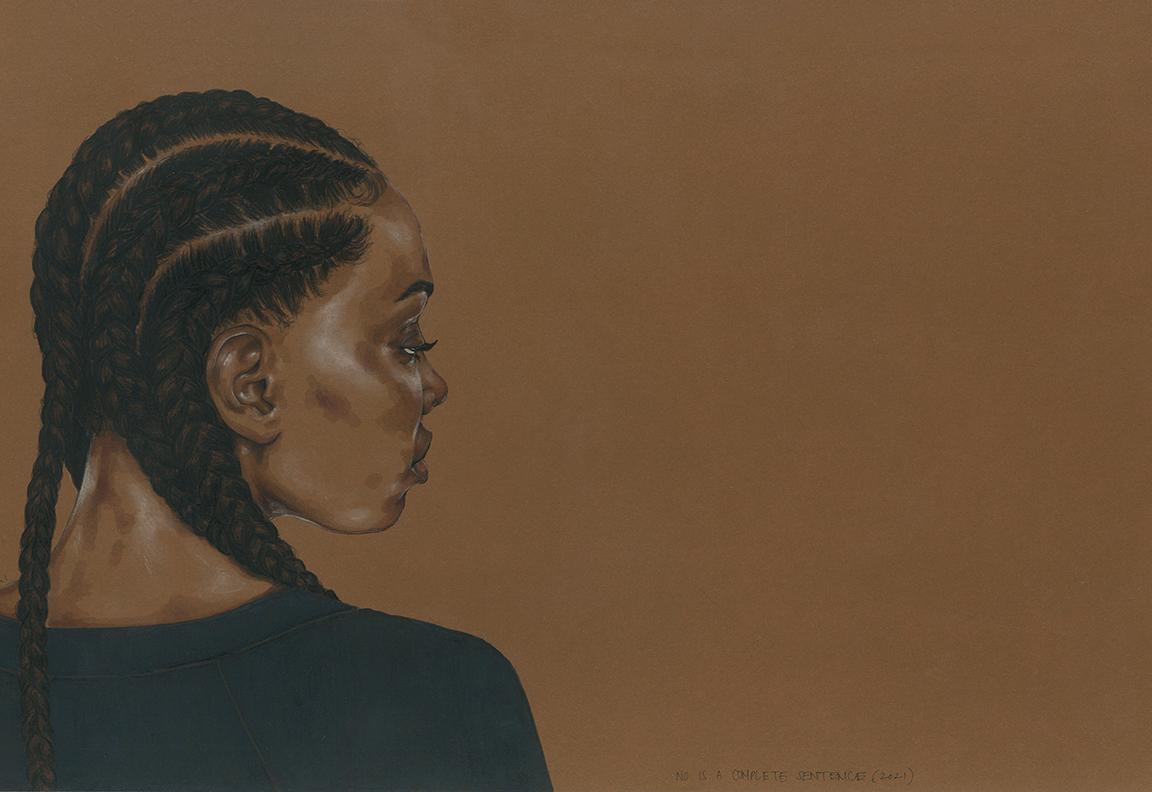

Ojo Agi, No is a complete sentence (No. 1), 2021. Courtesy of the artist. © Ojo Agi.

Foyer: How did you begin drawing?

Agi: I loved reading stories as much as creating them, so a lot of my childhood existed within the pages of a book or journal. I learned to draw through observation. I would draw the objects around me or copy the characters from my favourite television shows. I took any opportunity in school to draw, even if it was for a math or science class. During my undergraduate program in health sciences, I was drawing almost daily–a necessary creative outlet to accompany the biology, anatomy and chemistry courses I was enrolled in. I went to drop-in life drawing classes at a local community center, watched tutorials on YouTube, and connected with other artists on Tumblr. Although I did not get the opportunity to formally train, through consistent practice and self-directed learning I developed a dedication to the drawing medium.

Foyer: Your artist statement opens with, “There are always two stories happening in my artwork. One is the story that the paper tells. The other is the story that is represented on its surface.” Can you share in more detail what you mean by this?

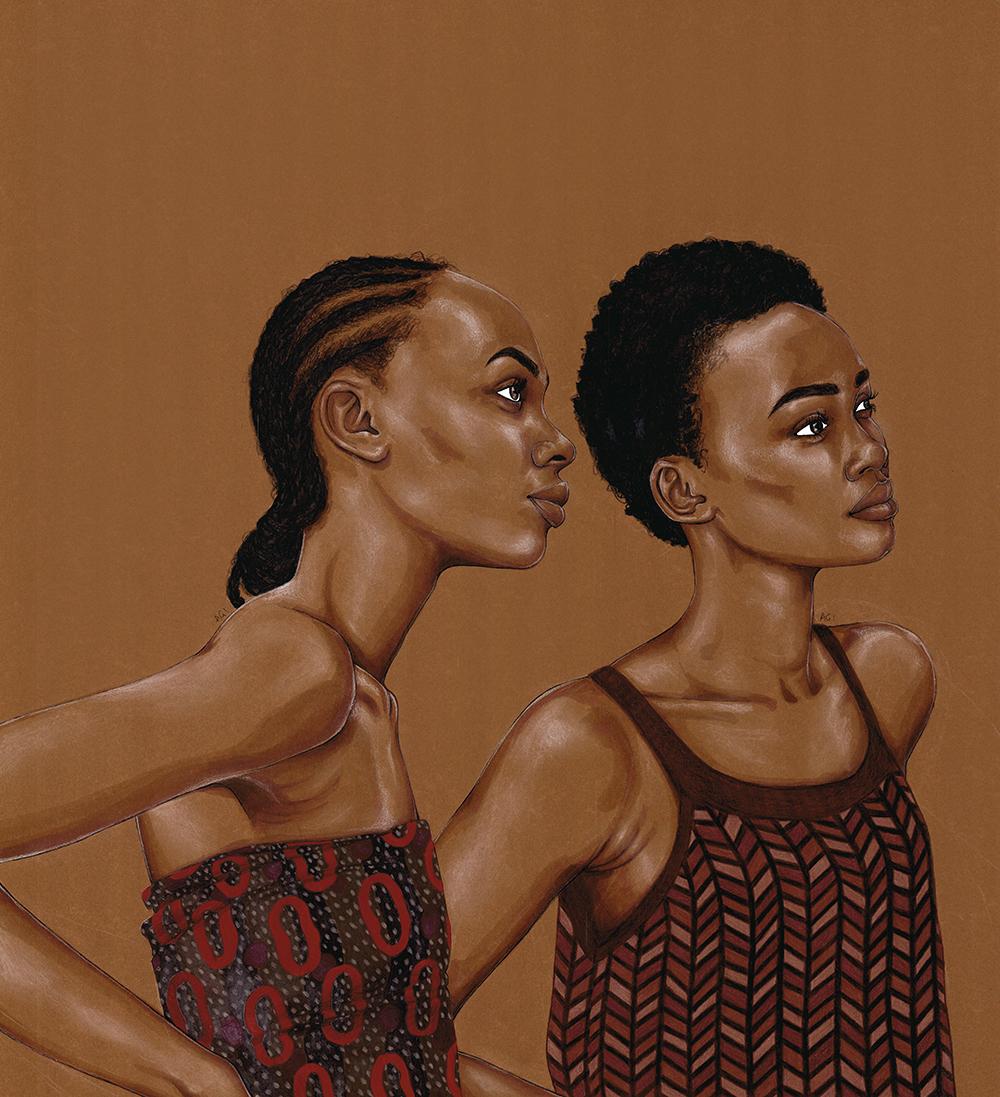

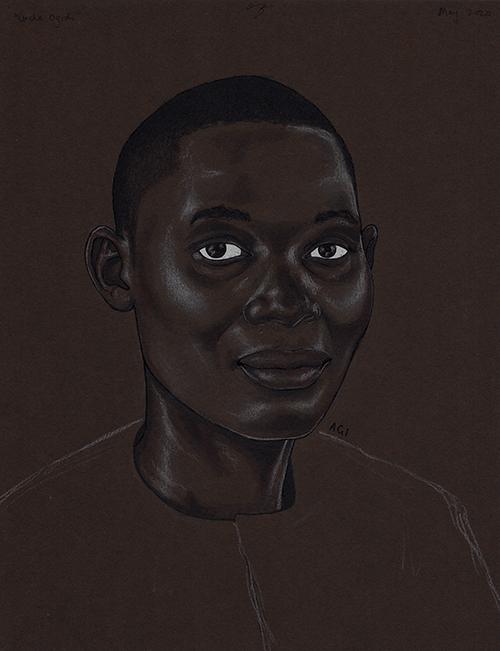

Agi: Yes! This is an idea I am still working out. Through studying art history, I have been learning to think more critically about my material choices. The images that I create are related to Black representation, cultural hybridity, and practices of self-care. The conversations I have around my work tend to relate to what is represented on the surface: the figure. But the paper is just as significant. It is noticeably brown, the same colour as the figure’s skin tone. I think about this as a metaphor for belonging. What does it mean to represent a Black figure in harmony with their environment? What does it mean to imagine a space in which Blackness is the norm, the context, the starting point? I think about these things often, as I am the first person in my family to be born in Canada and was raised in predominantly white or South Asian suburban neighbourhoods. I didn’t know a reality in which my Blackness wasn’t the first thing that people noticed about me, the thing that excluded me from so many spaces (literally and metaphorically). My parents grew up in a different reality. In Nigeria, where almost everybody is Black, it has a very different meaning. I wonder if, through this paper, I can claim a little bit of that experience for myself.

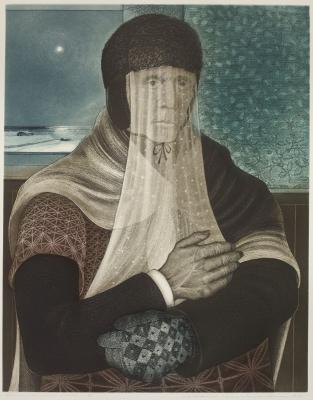

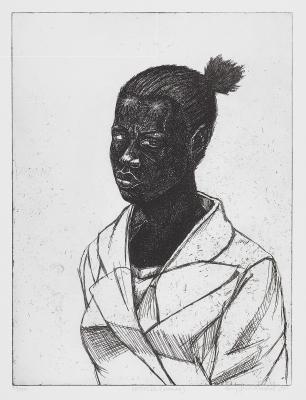

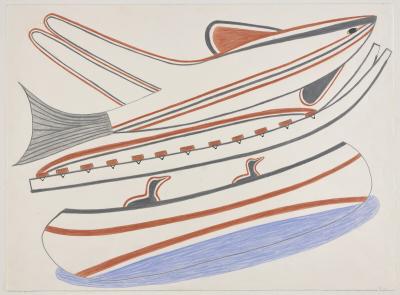

Ojo Agi, Uncle Ogidi, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. © Ojo Agi.

In doing so, I think the images I create have so much more power. They represent stories that are common across races–such as being a hyphenated Canadian or struggling with mental health issues–while unmistakably centering a Black character. It's about humanity, but it centers those of us who haven’t felt represented well in these narratives before. I intentionally draw the intricate patterns of our braided hair, the kinky curls that sprout from the nape of our necks, and the bright highlights that emphasize the darkness of the skin. It’s the details that affirm my identity while also finding me a place in these larger narratives.

Foyer: You started working specifically on brown paper over a decade ago. Why did you make that choice and how have your drawing skills/style evolved since that time?

Agi: I started working with brown paper around the same time that I started taking courses in women and gender studies during my undergraduate degree. I was learning (and unlearning) a lot about interlocking systems of oppression, which inspired me to think critically about the figures I was representing in my work. Until that point, very few of the characters I drew looked like me or my community. I was recreating what I thought was beautiful, and unfortunately that ideal did not even include myself. When I started making a conscious choice to represent dark-skinned, Black women, I had to change my approach to my materials. Trying to colour dark skin on white paper and achieve the smooth texture, nuanced shading, and variability in tone that I wanted was frustrating. So, I reasoned that I should simply start with brown paper. The first drawing I did was actually on the cover of a Moleskin journal. At first, I found it difficult to be able to see and distinguish the marks I was making. But with practice, I’ve developed my ability to observe light and shadows, to pay attention to details, and to effectively play with contrast to create form and likeness.

Foyer: Walk us through how you complete a drawing. What is your creative process like? Where do you start, and how do you know when you’re finished? How long does one drawing usually take?

Agi: I always start with the outline. I lightly sketch the shape of the figure in white coloured pencil. Then I gradually shade the skin, starting from the lightest colour to the darkest. In this part of the process, I am paying attention to where the shadows fall, and using a range of warm tones to create depth. Next, I apply and blend the highlights, paying attention to which areas of the face reflect light sharply or softly. Lastly, I work on the hair and add in remaining details to sharpen the expressive qualities around the eyes and lips. During earlier parts of the process, my hand is very free and loose. But in the detailed work, I am very meticulous and precise. It can take a few days to complete a small-scale portrait given the amount of detail involved in rendering a hairstyle like box braids.

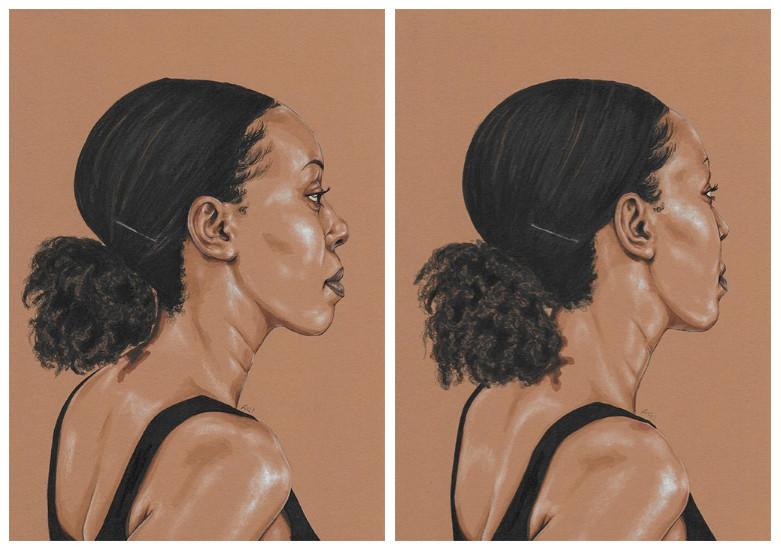

The question of when I am finished is really interesting. I have a lot of work that I consider complete that looks in a partial state of rendering. I incorporate its “unfinished” state into the storytelling, like in the drawing titled Becoming (2021). While working on this piece, I was reminded of a passage by the late British-Jamaican cultural theorist Stuart Hall: “We tend to think of identity as taking us back to our roots, the part of us which remains essentially the same across time. In fact, identity is always a never-completed process of becoming–a process of shifting identifications, rather than a singular, complete, finished state of being.” I really like that you can see the various stages of completion, such as the preliminary sketch of the figure’s hair and shoulders which would otherwise be obscured in one of my “finished drawings”. In a triptych titled Motion Study (2021), the figure’s face is fully rendered but her body is missing the highlights. I made this choice to help emphasize her gaze, which is shifting throughout each of the drawings. By enhancing the contrast of her eyes and diminishing the contrast of her body, the viewer is encouraged to notice her eyes' motion. These are not decisions that I make before I start the work; it happens during the creative process.

Ojo Agi, There will always be one more thing (diptych), 2021. Courtesy of the artist. © Ojo Agi.

Foyer: Tell us about the other ways you’re involved with art. What's on your plate right now?

Agi: In addition to making art, I also curate, program, and teach. In 2019, I curated and moderated a series of artists talks titled “In the Living Room” at the AGO during Mickalene Thomas: Femmes Noires. It was a wonderful opportunity to discuss approaches to representing Blackness with other emerging artists, including Jorian Charlton and Oreka James. In 2020, I worked with Feminist Art Collective to curate their annual exhibition and in 2022, I designed and taught a third-year course on decolonial approaches to portrait drawing for OCAD University. Right now, I am working through a PhD in Art History at Concordia University, continuing the work from my MA in Women and Gender Studies to bridge Black feminism with theories of representation to explore the works of contemporary women artists. As much as I love creating my own art, I’m also really passionate about materially and discursively contributing to an art ecosystem that empowers artists.

For more on Agi’s work, visit her website and follow her on Instagram. Catch up with our Illustrator series with this image essay by Moya Garrison-Msingwana.