Miniature Treasure Trove

Art historian Emma Rutherford traces the history of English portrait miniatures at the AGO

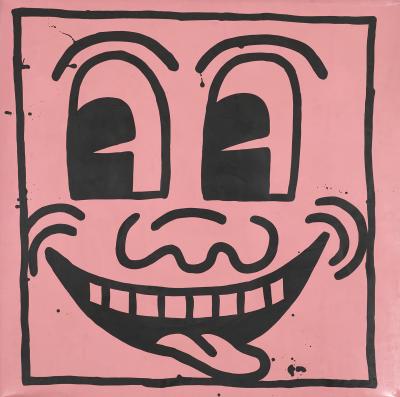

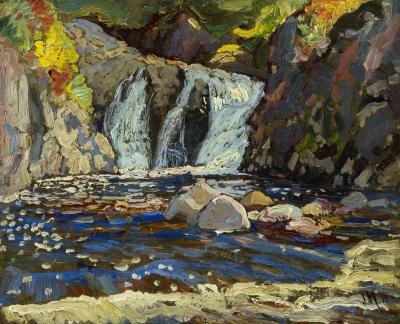

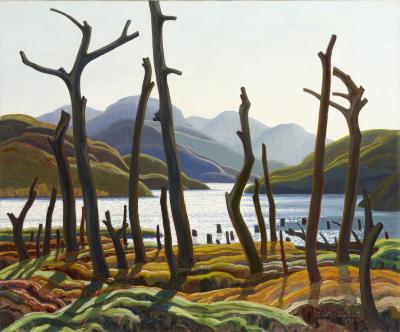

Nicholas Hilliard. Portrait of a Lady, 1582. watercolour on vellum, wood, Overall: 6.5 x 4.5 cm. The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Photo © AGO. 2025/616

Highly sought after in Europe for nearly four hundred years, portrait miniatures were once deeply personal objects—small enough to be held in the hand or slipped into a pocket. Often exchanged as tokens of love or remembrance, these jewel-sized paintings carry emotional weight, capturing likenesses, relationships, and moments in time with delicate precision. Because of this, they sit at the intersection of fine art, jewellery, and reliquary objects within the arts market.

The AGO is home to nearly 100 English portrait miniatures in its Thomson Collection of European Art. Dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries, the works are displayed in a three-sided, jewel-box gallery on Level 1 in Gallery 110. Entering through a darkened doorway, visitors encounter a display of rare miniatures by artists such as Nicholas Hilliard and John Smart. Mostly painted in water-based pigments on vellum or ivory — along with some in oil on metal or wood panel — these works showcase masterful technique on an astonishingly small scale.

On Wednesday, February 4 at the AGO, art historian and portrait miniature specialist Emma Rutherford will present a talk exploring this remarkable collection of nearly one hundred English miniature paintings at the AGO. Through the lens of these intimate works, Rutherford traces the history of miniature painting and shows how they offer insight into artmaking, politics, and personal relationships across centuries.

Emma Rutherford

One of the few art historians in the world specializing in portrait miniatures, Rutherford has worked with museums, curators, conservators, and auction houses for more than 25 years. Her research has led to significant discoveries, including the earliest known Black subject painted in miniature, the only signed work by Mary Queen of Scots’ favourite artist, Henri Decourt, and The Lost Portrait of Charles Dickens. In 2003, she founded The Limner Company to bring greater visibility to portrait miniatures through research, exhibitions, and contemporary practice.

Before her talk at the AGO, Rutherford spoke with Foyer to discuss her path into the field, the enduring appeal of miniature portraits, and what these small works reveal about the people who once held them close.

Foyer: What drew you personally to specialize in portrait miniatures?

Rutherford: I have always loved historical portraits, but the tactile, handheld, secret nature of portrait miniatures seemed to open a whole new portal into history for me.

Samuel Cotes. Portrait of Elizabeth Lynn, the artist's mother, 1775. watercolour on ivory, gilded copper alloy, wood, Outside: 8.5 cm. The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Photo © AGO. 2025/614

When did the genre of portrait miniatures begin in art history?

They begin in the early 16th century - simultaneously in England and France. For example, Henry VIII sends Anne Boleyn a bracelet with a portrait miniature set into it - sadly it no longer survives.

What are the stylistic qualities of a portrait miniature? What are the noteworthy techniques?

It's actually the materials and techniques that define a portrait miniature, not its size. Before around 1715, portrait miniatures were painted in watercolour on vellum, also known as parchment and after that date (although, no one has really got to the bottom of why), they began to be painted on thin slivers of ivory. Both of these techniques, particularly on a small scale, are incredibly challenging for artists, so most miniaturists committed to specializing in this field for life.

Richard Crosse. Portrait of James Crosse, brother of the artist, c. 1770. enamel, gilded metal, Overall: 10.6 x 8.6 cm, 0.5 cm. The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Photo © AGO. 2025/591

Portraiture focuses a lot on the dialogue between the artist and sitter. Does this also translate to portrait miniatures, too? Is there a similar dynamic?

I think even more so. The small scale of a portrait miniature meant that the artist and sitter had to be physically closer than a full-length oil. The focus is all on the face. When I examine the portrait miniatures of Henry VIII, for example, I like to look into his eyes and know they were staring back at a (possibly trembling) Hans Holbein or Lucas Horenbout.

Are there any standouts in the AGO's Thomson Collection of English miniature painted portraits?

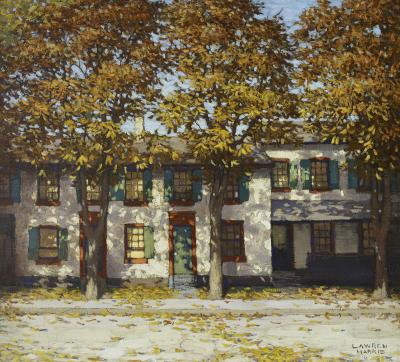

Actually, the AGO’s Thomson Collection has many standouts. It is a collection of great quality but also of broad breadth. The image on the front of the catalogue, British Portrait Miniatures from the Thomson Collection by Susan Sloman, is a particular favourite of mine (see lead image). It shows a 30-year-old woman wearing a fairly ordinary, everyday dress. People think that 16th-century miniatures were all refined and wealthy courtiers, but this portrait shows not only that Hilliard would paint whoever could afford him (Elizabeth I could, but she was always late with payment) but also offers an insight into a world outside the court. Staring frankly out at us, the thirty-year-old woman in this portrait looks as though she has just hung out her washing. That's the magic of miniatures, they offer such direct access to the past.

See the AGO’s curated collection of English portrait miniatures on Level 1 in gallery 110 as part of the Thomson Collection of European Art.

Tickets for Emma Rutherford’s talk at the AGO on the history of English portrait miniatures are now sold out. For more events, visit https://ago.ca/events/browse

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)