The Many Faces of Hebe

Introducing Mrs. Wells, the 19th-century British actress, who sought immortality in portraiture

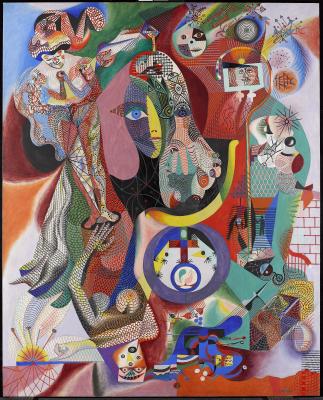

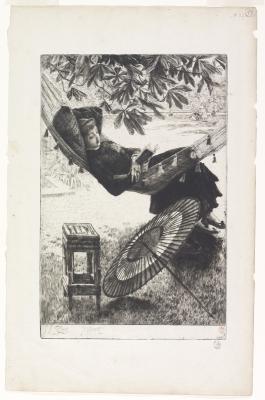

James Northcote. Mrs. Wells as 'Hebe', 1805. Oil on canvas, Overall: 127.6 x 101.6 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Bequest of J.J. Vaughan, 1965. Photo © AGO. 64/46

250 years ago, amidst a renewed interest across Europe in all things Greco-Roman, allegorical portraits—artworks depicting real people in the guise of mythological or historical figures—were the height of fashion.

Among the many mythological figures popularized during this period was Hebe, the Greek goddess of eternal youth. A favourite among women and artists alike, Hebe was youngest of all the gods, a daughter of Zeus and wife of Hercules. To be “en Hébé”, as the French would say, was to be portrayed in a scant white dress and sandals poised atop Mt. Olympus. Holding a golden kylix, or cup, bearing nectar, the likeness of the goddess was always chaperoned by Zeus in his adopted form of an eagle.

In form and figuration, Mrs. Wells as ‘Hebe’ (1805) is an exquisite example of this trend in portraiture, rehearsing as it does earlier works by more renowned neoclassical artists. English painter and the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) made a career of such portraits. A titan of British 18th century art, Reynolds's impact was immense and, today at the AGO, his influence is seen through this portrait by his student, friend, and biographer, British painter James Northcote (1746–1821).

Born in Plymouth, Northcote was initially apprenticed to his father as a watchmaker before abandoning the trade in favour of painting. He relocated to London in 1771, where his tutelage under Reynolds and subsequent study of Old Masters in Rome lent his portraiture credibility beyond their formal qualities. By 1805, when Mrs. Wells as ‘Hebe’ was completed, he had gained relative notoriety for the portraits and naturalistic animal scenes he showed annually at the Royal Academy. According to The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, his main claim to distinction was as a writer: “he was something of a character and a lively commentator on the artistic scene. The Memoirs of Sir Joshua Reynolds being his major publication.”

Described in a 1976 exhibition text as a “dazzling essay in social sycophancy,” Mrs. Wells as ‘Hebe’ features British actress Mary Wells (née Davies, occasionally called Becky, later Sumbel) posing in this iconic role. Even though Wells would have been 44 years old when the painting was made, Northcote’s portrayal reverses time to depict his subject as an embodiment of youth. The artist ascribes to Wells the regular features, curves, and porcelain complexion of classical Greek sculpture, set against a moody, indeterminate sky. Per convention, she holds an elaborate cup in her hand and is accompanied by Zeus in eagle form. That this work was not commissioned by Wells but instead presented at the Royal Academy of Arts’ annual exhibition and then sold suggests that the undertaking was likely a mutually beneficial arrangement.

An actress of some renown, Mary Wells (1761–1829) lived a life full of drama, on and off the stage. She first took the stage at age 14, and in 1778, while performing Juliet, married Mr. Wells, the actor playing Romeo. The union was short-lived; Mr. Wells abandoned her for a bridesmaid. Mary made her London debut in 1781 and throughout the next decade earned praise for her comedic roles, often under the stage name of Becky Wells. She gave birth to four daughters and, by 1797, had been imprisoned in debtor's jail. There, she met and married the secretary to the Ambassador of Morocco, one Joseph Haim Sumbel, a rumoured millionaire imprisoned for contempt of court. For him, she converted to Judaism and changed her name to Leah Sumbel. A year later, she tried to have him arrested for murder and, following a lengthy public spat, he fled the country. She returned to the stage and continued to use his name. We know this much, for in 1811 she published a sprawling three-volume autobiography, Memoirs of the Life of Mrs. Sumbel, Late Wells. Despite these efforts, she died in poverty in 1821, still estranged from her children.

“She is remembered”, writes Sarah Murden, 18th century historian and author of The Life of Actress, Mary Wells, “as a great actress whose eccentricity and misfortunes prevented her from reaching her full potential.”

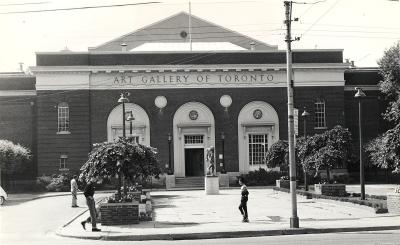

A cherished part of the AGO’s collection of European Art, Mrs. Wells as ‘Hebe’ was first exhibited at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now AGO) in 1920. The painting was gifted to the museum by J.J. Vaughan, an executive at T. Eaton Limited, together with Anthony van Dyck’s portrait Michel Le Blon (1630-35) and Sir J.W. Gordon’s portrait Master David Murray (c. late 18th century) in 1965.

On view now in Richard Barry Fudger Memorial Gallery (gallery 125), installed between James Tissot’s The Shop Girl (1883-1885) and Nicolas-André Monsiau’s Zeuxis Choosing his Models (1797), Northcote’s portrait is a beguiling expression of the neoclassical impulse and flair for the dramatic. Uniquely surrounded by portraits of working women from the 19th century, here finally Mrs. Wells has achieved, in some part, her desired immortality.

Mrs. Wells as ‘Hebe’ is on view now in the Richard Barry Fudger Memorial Gallery (gallery 125) on Level 1 of the AGO.