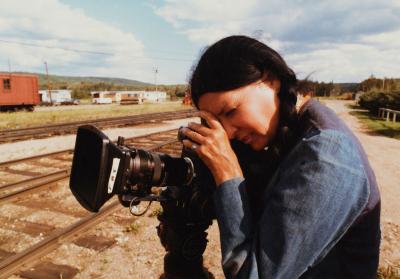

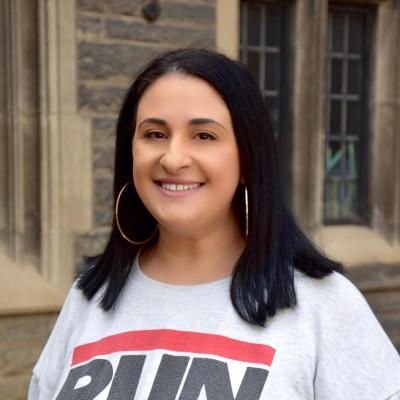

Toronto’s lo-fi R&B gong punks

The Toronto-based group Pantayo explores queer, Filipinx diaspora through music

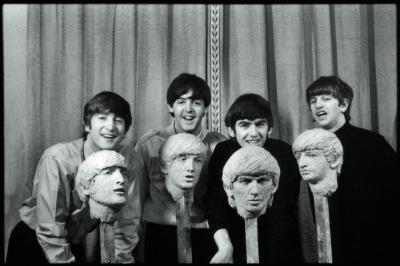

Photo credit: Felice Trinidad

Fitting into a box has never been easy — nor the goal — for Toronto-based band Pantayo. Applying for festivals, the group is constantly left with the dilemma of what genre to tick on the intake form. R&B, Pop, Other, or even the category, World Music, often makes do for the genre-bending group. However, the words that best describe Pantayo go beyond musical genres: Filipinx, Queer, diasporic, and musically innovative.

Eirene Cloma, Michelle Cruz, Joanna Delos Reyes, Kat Estacio and Katrin Estacio, laid the roots of Pantayo in Kensington Market, the five meeting at the Kapisanan Philippine Centre for Arts & Culture in 2012. There, they bonded over their desire to learn Kulintang, an ensemble of traditional Filipino instruments indigenous to Mindanao, the southernmost group of islands now known as the Philippines. The ensemble's namesake, kulintang, is a row of horizontal gongs that increase in pitch from left to right. A kulintang ensemble also includes the agong, a suspended gong; the gandingan, the secondary melodic instrument in the ensemble also known as the talking gongs; and the dabakan, a single-headed drum.

Without a formal teacher, the group committed to learning kulintang, sneaking into the University of Toronto classrooms twice a month to practice together and create songs. Fast-forward 11 years, and the group has released their second album, Kulintang remaining a constant as they developed their musical style over the years.

All queer and Filipinx musicians, Pantayo’s genre-bending music style is symbolic of the group's diasporic experiences as a mix of first and second-generation Canadians.

“We only categorize our music because of the requirements, but we feel our music [can’t be] boxed in,” Cruz explained. “Our music is based on our experiences as queer Filipinxs having lived in different parts of Canada... It’s a really colourful vibe.”

“We were laughing at the [categorization] of World Music because it's so antiquated and problematic,” Kat added. “Ultimately, we use kulintang as a vehicle for expression. No matter what the expression is, it takes form in different musical styles.”

Photo credit: Felice Trinidad

Blending kulintang with various music styles isn’t an easy feat. While some of Pantayo’s songs are beautifully composed with only kulintang, the communal nature of kulintang’s creation means the gong dictates how Western instruments fit into Pantayo’s compositions.

“We could liken the [kulintang] to the marimba or xylophone… the only difference is with kulintang it’s made in a community setting, meaning the maker would tune the gongs to whatever they see fit [for the community], not to a scale,” Katrin explained. “We have to choose chord patterns and progressions that would make sense for the gongs. [Our process] starts with what works with the gongs, and then we work from that.”

Beyond working around the specific tuning of the gongs, another challenge for the group is feeling legitimate in their art as queer Filipinx musicians. Growing up with parents who idolized American music due to American imperialism in the Philippines, Cloma often struggles to feel like Pantayo’s work is truly valued.

“[There’s] a cultural marginalization of Filipinos, and we’re not seen as cultural contributors, but the reality is, Filipinos have always been here working on music— we’re just invisibilized in a lot of ways,” they said. “Filipinos have been working overseas performing American pop music of all genres, but it’s not seen as a real cultural contribution because the labour is cheap… As a Filipino creator, I’m always fighting this idea that my music isn’t as good as white or other racialized artists.”

While there are challenges to being unapologetically Filipinx and queer, there is also comfort in this authenticity, both for the members of Pantayo and their fans. Cruz likens Pantayo to therapy, a safe space to explore topics she avoided like her sexuality. For Kat, sharing this intersection of identity has opened up creative avenues.

“I’ve always known I’m Filipino, I’ve always known I’m queer, but I never really thought about expressing it in art and music in the way we are with Pantayo,” she said. “There is this level of understanding when we’re working in a group — I don’t have to explain my identity… and it activates creativity in a very different way for us. In the same way, when we’re able to express ourselves authentically… that brings connection to people who listen to our music and can relate to our philosophy.”

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/R03sUSksNv4.jpg?itok=wuhWZVhV","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R03sUSksNv4","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0,"title_format":"@provider | @title","title_fallback":true},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

Their newest album Ang Pagdaloy, which was released June 9, is representative of what it took to create it. Meaning “to flow” in Tagalog, the album is all about letting go.

“There were some challenges in creating material for the record, and we found ourselves surrendering to the flow — surrendering to the path of least resistance,” Kat said.“It’s not the easiest to let go and let it flow, but it was the simplest way.”

The concept of flow also ties into how Pantayo’s music is a mirror of who they are and how they experience the world.

“The album is a reflection of who we were at that moment,” Cruz added. “You continue to grow or evolve… and grow your perspective as the days and months and years go by. It’s like our memoir. The inspiration [for this album] is our experiences.”

Join Pantayo in celebrating the release of Ang Pagdaloy at their album release party on June 30. Grab tickets here.