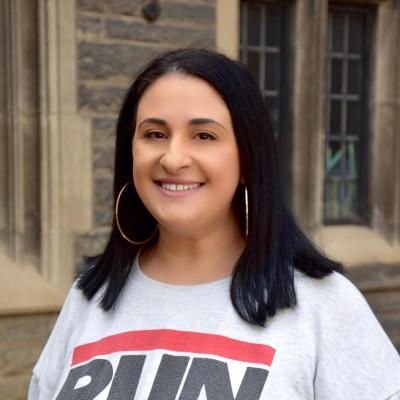

The legacy of steel pan with Suzette Vidale

The renowned Toronto pannist shares her thoughts on an enduring tradition.

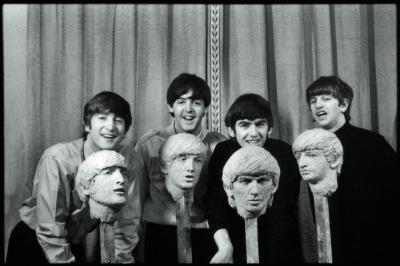

Image courtesy of Suzette Vidale

Black Futures month at the AGO kicked off with a bang, welcoming Sharon Marley for a live performance in Walker Court, then hosting a screening of RasTa: Soul’s Journey (featuring Donisha Prendergast). Next, on the evenings of Friday February 16 and 23, visitors will enjoy the musical stylings of one of Toronto’s most well-known steel pannists. Live from Walker Court, accomplished musician, educator and a leader in Toronto’s steel pan community, Suzette Vidale will be sharing the joy of pan in two exclusive performances.

This isn’t the first time that AGO visitors have encountered the sweet sounds of Vidale’s pan. In 2021, she performed live in Walker court in celebration of the AGO exhibition Fragments of Epic Memory. At the time, she sat down with Foyer for a chat, and we’re revisiting that conversation now.

The steel pan was born out of resistance in 1930s Trinidad and Tobago; many believing its exact birthplace is the capital city of Port of Spain. When French planters arrived in Trinidad in the 1700s, they brought with them enslaved people from West Africa. It is said that these enslaved people, barred from participating in Carnival with their enslavers, used sticks and bamboo to make percussion instruments (like the tamboo bamboo) to play during their own version of Carnival, only to have these instruments banned by their enslavers quickly thereafter. Eventually, in the post-emancipation years, formerly enslaved people continued to invent musical instruments. Discarded metal objects like dust bins and car parts were turned into instruments by street musicians. Enter the oil drum in 1934; hammered, polished and tuned to play. “Oil drums,” explains Vidale, “had a greater surface area to accommodate more [music] notes and produce more sounds.” The steel pan has endured in years since then, expanding well beyond the shores of Caribbean islands. To learn more about her career and the steel pan in Toronto, we spoke with Vidale.

Foyer: How did you get your start as a steel pannist?

Vidale: In 1993, my mother encouraged me to play. I wasn’t interested at first, but a good friend named Monifa Colthurst invited me to an Afropan Steelband rehearsal. I remember it as the first time I really saw steel pans up close. They were illustrious and they pulled me in closer. Once I heard the sounds and felt the vibes, I was hooked.

Foyer: How have you seen Toronto’s steel pan community evolve throughout your career, especially as the instrument and its sound have become more widespread?

Vidale: Toronto is a melting pot and you can see that reflected within the bands. There’s more diversity. In some bands, more than half of the pannists are women. Pannists are getting younger as the years go by.

Toronto’s steel pan community was originally closely associated with Caribana. In the decades since Caribana’s inception in 1967, I have seen steel bands and pannists participate in diverse events, ranging from non-Caribbean cultural festivals to Pride, and international film festivals.

As audiences listen to the various steel bands around the city, they realize that many of the stereotypes they hold of steel bands and steel pannists aren’t based on reality. Many times, they might expect to see a male player and hear calypso and reggae but are often shocked to see a female player and hear classical music, R&B, Hip Hop or other cultural pieces from various parts of the world.

Aside from seeing the steel pan being incorporated into educational institutions at all levels, my most favourite shift is the inclusion of the instrument as a wellness tool. I have had some of the greatest moments connecting with our city’s most vulnerable citizens. I am always learning from others while doing steel pan workshops for the homeless, at-risk youth as well as marginalized women who may have experienced trauma.

Foyer: What goes into preparing for solo and group steel pan performances? Do you prefer to improvise or play a setlist?

Vidale: Depending on the event, you may have new pieces to learn if there is a specific theme For International Women’s Day, for example, I would perform inspirational songs about female empowerment. I try to have a diverse repertoire so I can easily add to the atmosphere of the event where I am performing. I generally know what I would like to play, but once I arrive in a space, I take my cues from the audience. Sometimes, you completely change your set.

Foyer: Why do you think the steel pan has endured as such a strong part of Caribbean culture, even beyond its roots in Trinidad and Tobago?

Vidale: The steel pan was born out of necessity. The spirit of the drum is the heartbeat of its people. The steel pan and its community are inclusive, allowing for friendships to form through music, transcending race, religion, gender and borders.

Don’t miss Suzette Vidale at the AGO live from Walker Court on Friday February 16 and 23. Free with admission.