Inside David Blackwood’s Studio

Janita Wiersma details her experience as Blackwood’s studio assistant

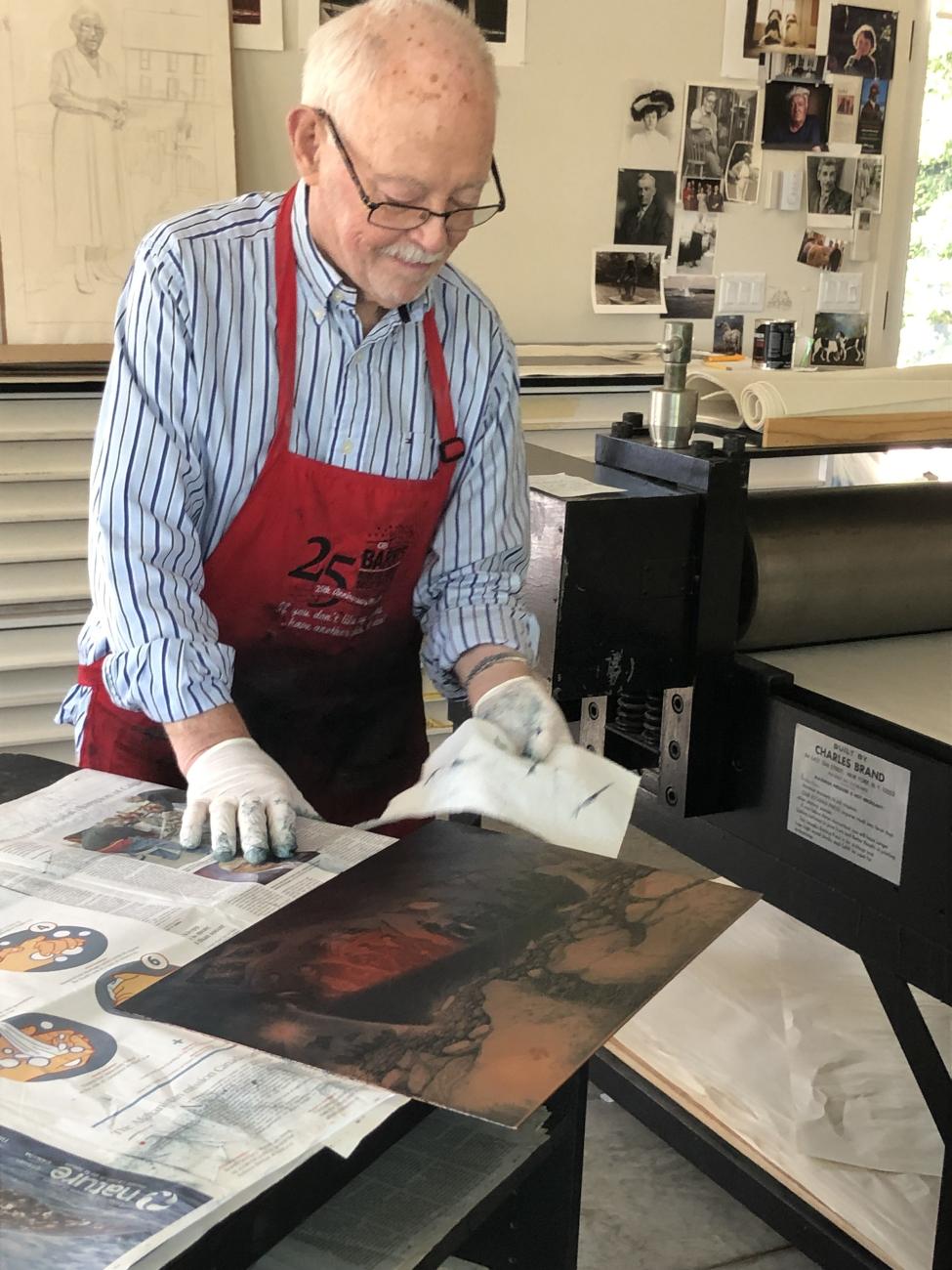

David Blackwood, 2020. Photo by Janita Wiersma.

“He felt that the copper plate was like a piece of music; everyone interprets it differently, and he wanted to play it the way he heard it.”

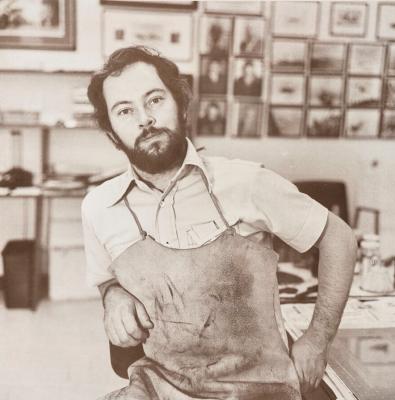

As a student of printmaking Janita Wiersma always had an acute awareness of David Blackwood’s impact on Canadian art, but it wasn’t until she became his studio assistant in 2011 that she truly understood the complexity of his creative process.

Her journey alongside Blackwood began when she had just returned home from studying for a Fine Arts degree with a focus on printmaking at Mount Allison and Concordia Universities. Over the next eleven years, Wiersma evolved from an awe-struck rookie assistant to an integral part of Blackwood’s practice, and a beloved friend to the legendary printmaker. She supported Blackwood’s work during his long recovery from a life-threatening illness and in his final days of practice before his passing in 2022.

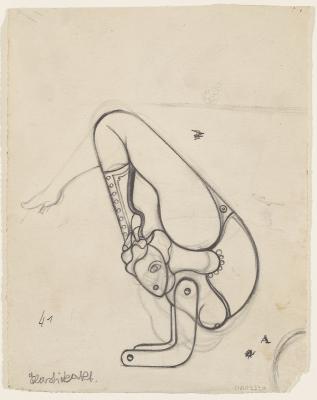

Wiersma carries a deep knowledge of Blackwood’s approach to printmaking. Developed over the course of his career, his process consisted of several key phases: a full-scale pencil drawing, transferring this drawing to the plate, applying a powdered resin known as 'aquatint' for texture, etching the plate with acid, and printing a series of 'proofs' to check the development of the image through to its final stage.

In this image essay written for Foyer, Wiersma details her experience assisting Blackwood with four of his seminal works. For each, she shares technical insight and personal anecdotes that illuminate her special relationship with Blackwood. All these works are on view now as part of David Blackwood: Myth & Legend at the AGO.

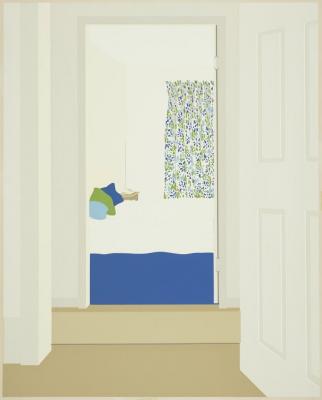

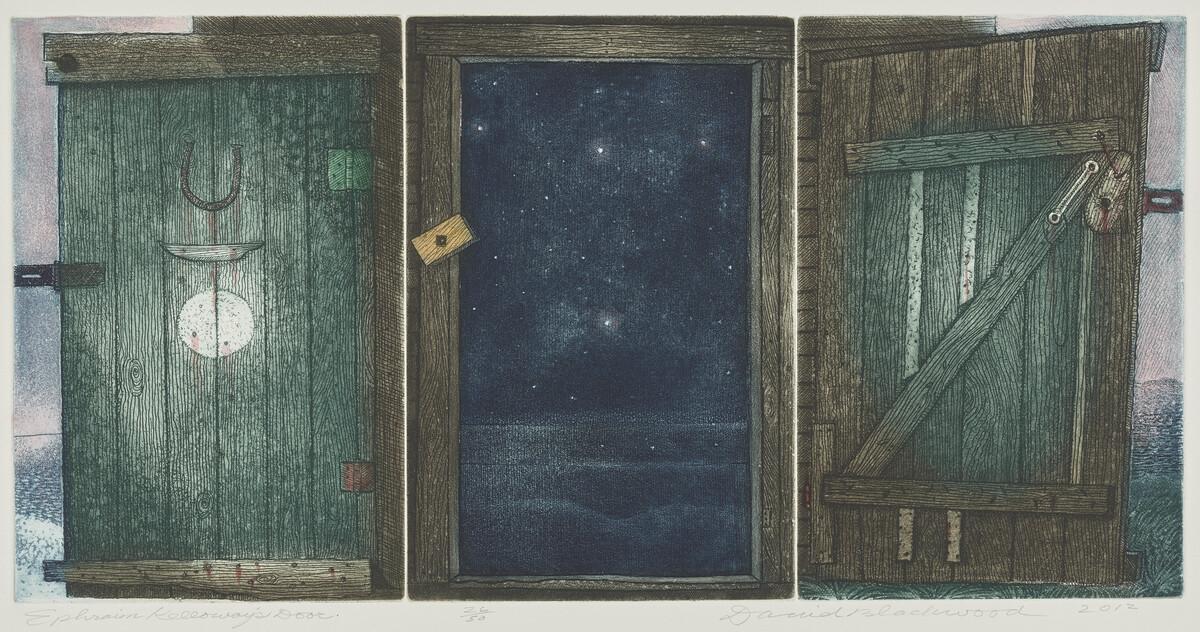

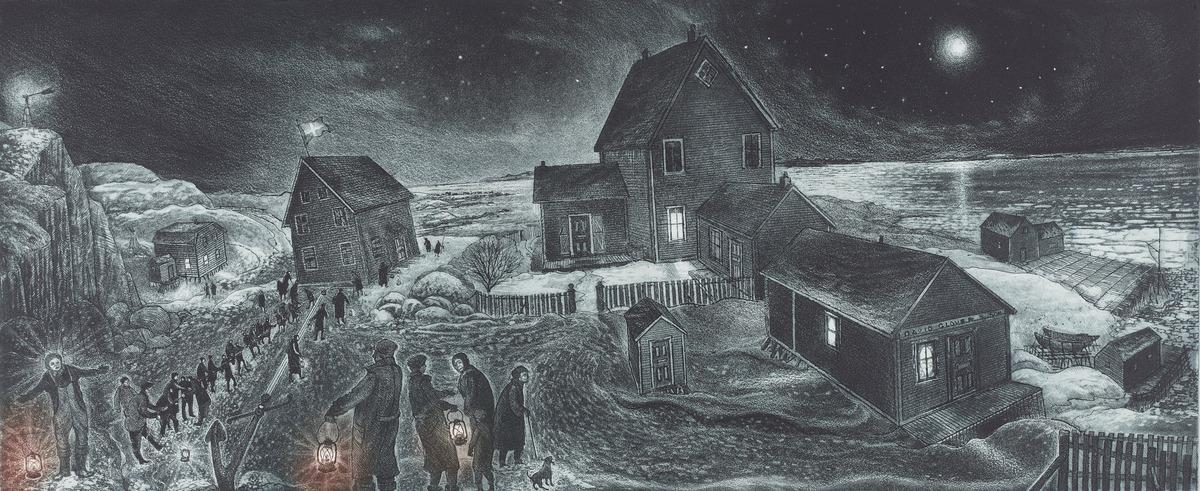

Ephraim Kelloway's Door (2012), triptych

Etching and aquatint, with hand-colouring on wove paper

David Blackwood. Ephraim Kelloway's Door (Triptych), 2012. Etching, aquatint, watercolour. Plate Mark: 30.5 × 60.9 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario. © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO.

I started working as David 's studio assistant in 2011, shortly after moving back home to Northumberland County after ten years away. I studied Fine Arts with a focus on printmaking at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick and Concordia in Montreal, and I remember feeling absolutely awe-struck to be in David Blackwood's studio, watching him print...helping, even.

This is one of the first etchings I remember David working on. It’s made from three separate plates each inked individually, then set side by side on the press and printed on a single sheet of paper. Preparing the paper for printing was one of my tasks, and David always reminded me to be generous. We would have printed this smallish etching on a full sheet of fabriano paper (30"x40") and then trimmed it down once it was dry.

The brightness of the stars in the middle plate, shining in the darkness, from David's careful wiping of tiny smooth spots on the copper plate. He used a tightly wrapped paper tool normally used for smudging charcoal or graphite in drawing to wipe these areas clear of 'plate tone'; the residue left from the oily etching ink. He often wiped certain areas of the plate more closely to allow the white of the paper to shine through and glow like a star or a lantern.

I really love that this image is created as a triptych - traditionally a form of three panels used as a religious altarpiece - to tell the story of Ephraim Kelloway's door. We see the two sides of the door, and just as importantly as the object itself, the infinite world the door opens upon.

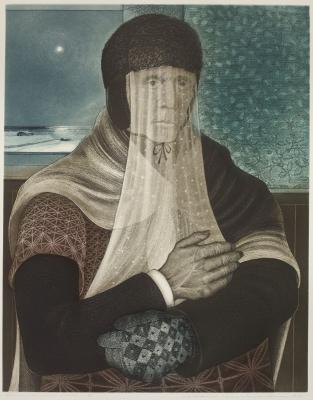

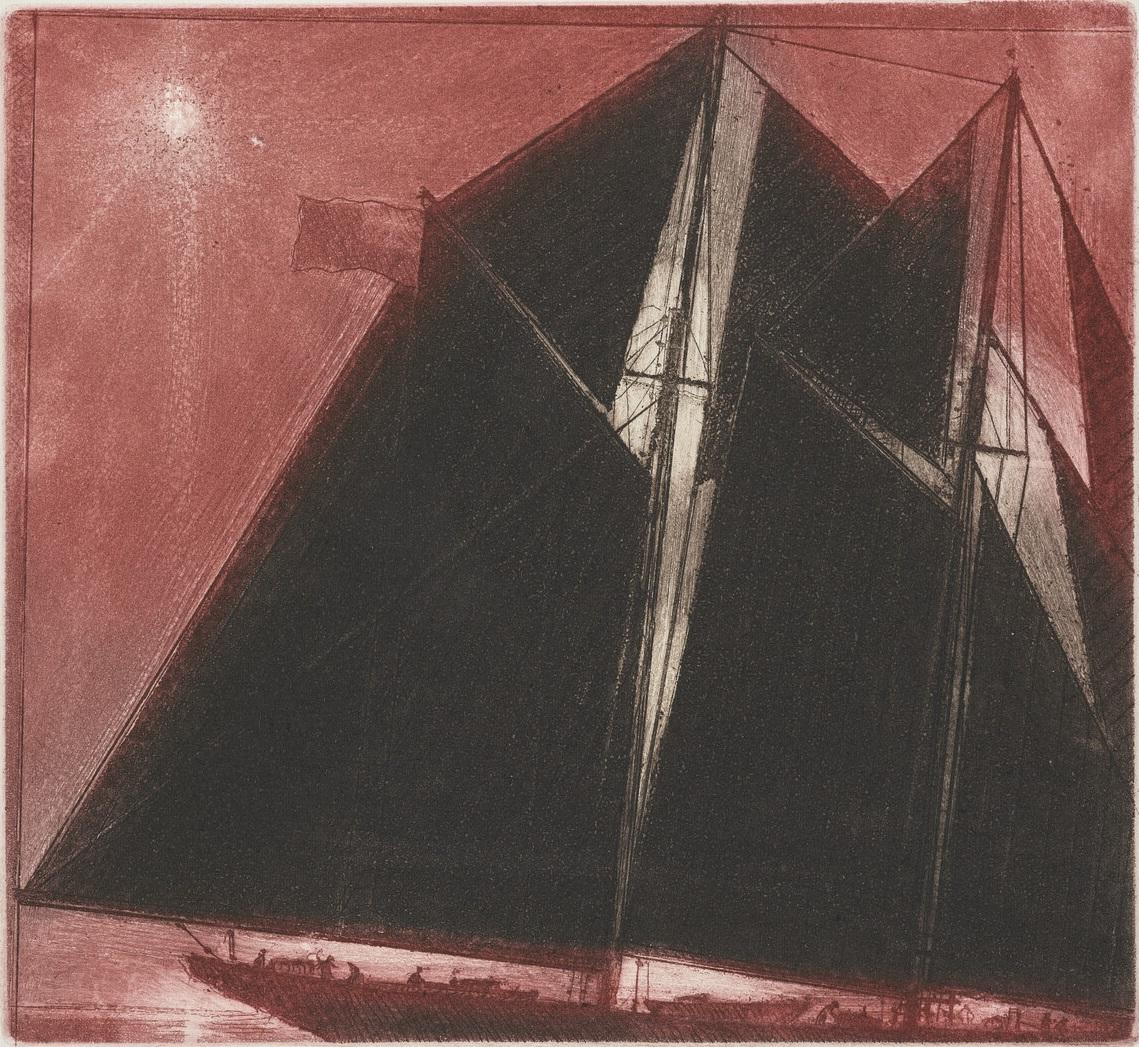

The Nickerson Passing (2015)

Etching, aquatint

David Blackwood. The Nickerson Passing, 2015. Etching, aquatint, Plate Mark: 16.7 × 18.2 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO

This is one of the etchings David was working on while he was at Bridgepoint Hospital in Toronto, recovering from a long illness. It was the first “study” piece for a much larger etching he completed in 2019, The Nickerson Passing on our Starboard Quarter, which also appears in the AGO exhibition David Blackwood: Myth and Legend. A case in the final room of the exhibition tells the story of Flatty: how David’s wife, Anita, carried the plate and various proofs back and forth between me in the studio in Port Hope and David in Toronto. The same was true for the creation of this little etching.

This period is notable because aside from The Nickerson Passing, Flatty and parts of a few other images, David produced and printed all of his own plates. He felt that the copper plate was like a piece of music; everyone interprets it differently, and he wanted to play it the way he heard it.

Until this time during David's recovery, my role in the studio had been largely supportive - preparing the water tray, soaking and blotting the paper before printing, and taping the damp prints to boards to dry. But suddenly I found myself working on the plates much more directly.

The first step in etching is to prepare a new copper plate by coating it in a waxy ground called asphaltum, to create an acid-resistant surface. Often the plate is gently heated, so the asphaltum spreads evenly. Once the ground is dry, the image can be transferred onto it with tracing paper and then drawn through with a sharp tool called an etching needle, which removes the ground to expose the copper beneath. These exposed areas will ultimately be 'bitten' into the copper plate with acid, creating the first stage proof.

I prepared the plates by coating them with ground, and then David, at Bridgepoint, transferred his drawing onto the plate and used an etching needle to draw through the asphaltum. Back in the Port Hope studio, I etched the plate by lowering it into an acid bath, a mixture of water and nitric acid, following detailed instructions sent by David. The longer the plate sat in the acid, the more the exposed copper was eaten away, and the darker the lines would be in the final print. Too long, and the fine detail of the lines would begin to break down as the acid bit deeper and deeper, so I kept a very close eye on the plate.

After etching, I cleaned off the wax ground and printed a few impressions for Anita to take back to David. A few days later she would return with new instructions, and the process would begin again.

This was a thrilling and poignant experience for me. On one hand, I felt honoured to be entrusted with the etching, aquatint, inking, wiping, and printing of a Blackwood plate; on the other, the studio was too quiet. I missed the storyteller and would much rather have had him there doing the work he loved so well.

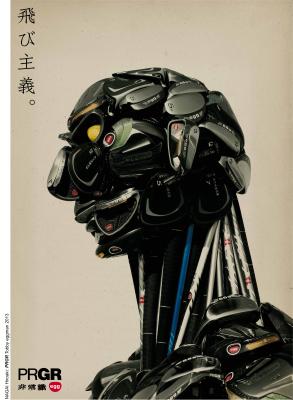

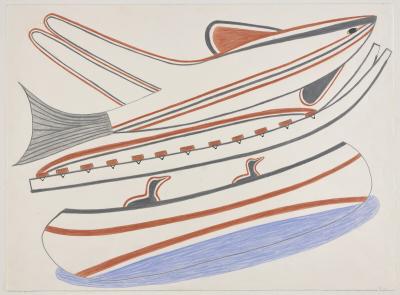

Hauling Oram's House, 2018

Etching, aquatint

David Blackwood. Hauling Oram's House, 2018. Etching, aquatint, Plate Mark: 38.2 × 90.9 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO.

In 2017, David and Anita moved from the home they had lived in since the early 1970s. The move also meant leaving behind David’s expansive two-story painting and printmaking studio and temporarily setting up shop in the attached garage of their new house while a new studio was built on the property. Hauling Oram’s House was started during this garage-studio period, which actually proved quite convenient, especially for ventilating the often-potent fumes associated with printmaking: varsol, asphaltum, and, on one memorable occasion, while etching Hauling Oram’s House, the gas produced by immersing a copper plate in a fresh, strong batch of nitric acid. The acid worked much faster than expected, and David quickly realized he had to pull the plate out long before the timer ran out.

The plate was bitten more deeply than intended, resulting in a darker aquatint than planned. But I never once saw David become frustrated or give up on an image. He always found a way to work with the plate, scraping, burnishing and re-etching; guided by a genuine curiosity about what might emerge next. In this case, I think that the overbitten aquatint ultimately enriches the atmosphere of the scene.

David is often described as a master printmaker for his extraordinary command of intaglio etching, but watching him work over the years, I came to understand that this mastery grew from qualities deeper than technique; it was his curiosity, resilience, and quiet determination to keep exploring ways to tell his stories that stands out. He never tried to “master” the plate so much as collaborate with it, allowing the process to lead the way.

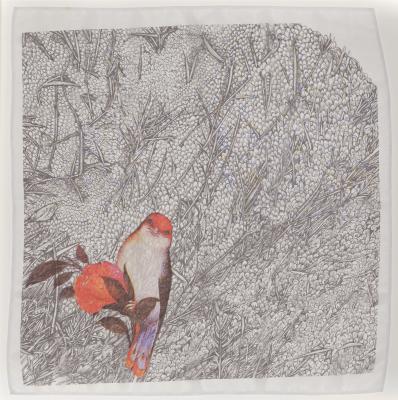

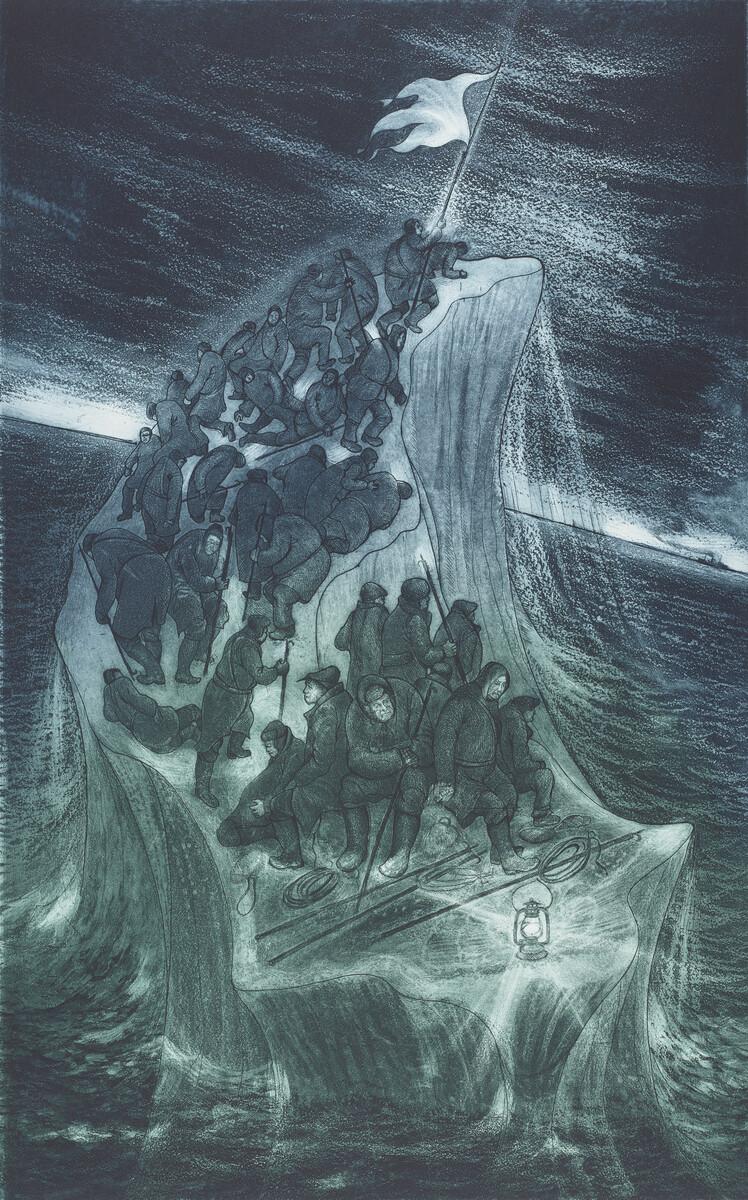

Search Party Lost (1970-2021)

Etching, aquatint

David Blackwood. Search Party: Lost, 1970-2021. Etching, aquatint, Plate Mark: 80.8 × 50.7 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario. © Estate of David Blackwood.

This plate is a special one, and its title carries a double meaning: it depicts a search party that has become lost during their mission, and the plate itself was also lost for more than forty years. The image is inspired by Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, and it’s easy to see why a young David, already creating work about naval disasters, would be drawn to Géricault’s epic painting of men adrift at sea.

As the dates in the title indicate, the plate was begun in 1970 while David was living and working in Toronto. Though over the course of his career this was a rather rare occurrence, the initial line etching for this image was also over-bitten. Around this time David was moving his studio from Spadina Avenue to the University of Toronto’s Erindale College campus, and somewhere in that transition the plate went missing. Over the next forty years, and through at least four more full studio moves, the “lost” plate never resurfaced, and David feared it was gone for good.

The 2017 move of house and studio required placing some items in storage. Among them,the more than 200 copper plates David had produced up to that point. As we packed them away, David wondered again what might have become of the missing plate. A year later, once a proper filing system was in place, I began transferring the plates from storage and cataloguing them as I went. It was a slow process, and load after load yielded no sign of Search Party.

I found it when I was loading up the very last of the plates from storage. David wasn't a very excitable person, but he glowed when I brought this plate back into the studio. He pulled a proof to check the line work, and it wasn't so deeply bitten after all.

For David, the next step was often layers of aquatint. He would isolate an area of the image and work on it, giving it the texture it needed, and then move on. The iceberg, for example, would need a more lightly etched aquatint than the water and sky, so he would work on it by covering the rest of the plate with an acid resist.

David often used a technique for adding colour to a single plate called à la poupée, in which coloured inks are applied to the plate using a small, doll-shaped wad of fabric, unsurprisingly called a poupée. David, however, adapted the method by carding the ink onto the plate with variously sized strips of stiff plastic. The effect was the same: areas of the plate were charged with the glowing red of a lantern, the deep green of the sea, or the cold blue of an iceberg. When the plate was then carefully wiped with a stiff cloth, the colours blended to produce a single printed image containing multiple colours. Another example of his expertise in etching.

Interestingly, when David resumed work on this plate in 2021, he added the ship on the horizon. Whether it represents hope, approaching the stranded men, or despair, steaming away from them, remains uncertain. I never asked. It was simply extraordinary to watch a plate that had been paused for four decades to begin to take shape again.

David Blackwood: Myth & Legend is on view now until July 2026 on Level 1 of the AGO. The exhibition is curated by Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints and Drawings at the AGO.