David Blackwood Book Launch October 18

AGO Curator Alexa Greist explores Blackwood's legacy as a renowned printmaker

Coinciding with the opening of the exhibition David Blackwood: Myth & Legend at the AGO, a new hardcover book of the same name offers an exploration into the celebrated printmaker’s art and life. The publication features texts by Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints and Drawings, AGO and Amy Marshall Furness, former Rosamond Ivey Special Collections Archivist & Head, Library & Archives, AGO.

With over 80 full-colour reproductions, the book highlights Blackwood’s creative process through his drawings and prints, alongside proofs, copperplates, and archival materials.

Curated by Greist, the exhibition David Blackwood: Myth & Legend opens to Members on October 8 and Annual Passholders and the public on October 14 at the AGO.

A book launch event will follow on October 18, featuring a conversation with Anita Blackwood and Greist. To delve deeper into Blackwood’s legacy, we turn to an excerpt from the book written by Greist.

Never Disappointed: David Blackwood, Printmaker

“At this point, we have no idea of what lurks beneath the surface! Regardless, there is never disappointment.” - David Blackwood

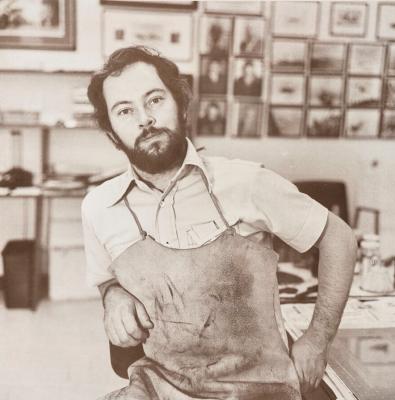

David Lloyd Blackwood (1941–2022) was an artist who discovered two key elements early in his artistic trajectory: his ideal medium of intaglio1 printmaking and his defining subjects: the lifestyle of his childhood and the enduring landscape of Newfoundland and Labrador. Blackwood worked primarily in etching with aquatint and embraced the possibilities of the copperplate; not for its experimental and abstract linear qualities—as was the main interest of the Ontario College of Art (OCA) printmaking studio, where he began his formal studies at the age of 18 in 1959—but rather for its properties that allowed simple line and tone to create immersive effects This experimentation opened an entire world in his hands.2

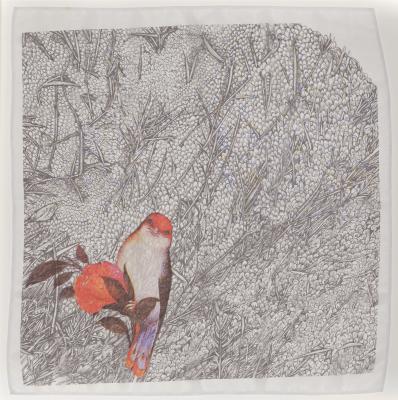

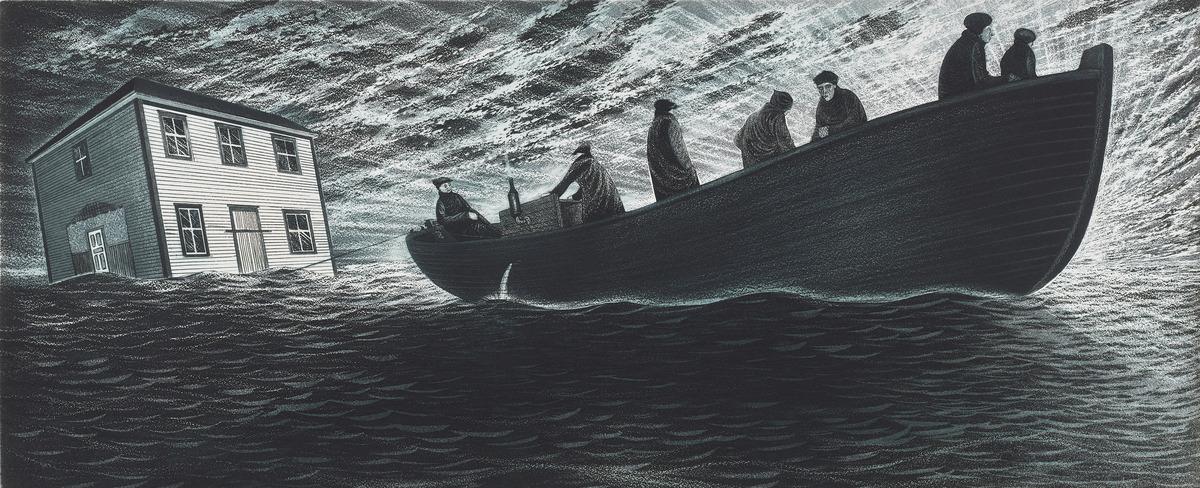

Using a restrained palette of inks on a diverse field of intaglio textures, Blackwood used colour sparingly and to great effect; warm, and even violent, reds and oranges punctuate dark seas and skies in many of his most famous prints. There are exceptions, such as interior scenes where the richness of accumulated textiles and domestic decorations reflect the warm nature of home. He captured the outport spaces that disappeared with the resettlements, or centralization, of their residents through various government programs under Newfoundland Premier Joseph Roberts Smallwood from 1949 to 1972. Many of the artist’s prints seek to preserve spaces that were either torn down or moved to other locations, in addition to the vanishing ways of life that had brought people to settle in the harsh climate of the outport settlements in the first place.

David Blackwood. Uncle Eli Glover Moving, 1982. Etching and aquatint on paper, Overall: 46.6 x 97 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of David and Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario, 1999. © Estate of David Blackwood. 99/963

During his printmaking career, Blackwood worked through his large, narrative prints in much the same way. He began with smaller sketches that led to an overall pencil drawing at the same scale as the plate.3 He might have played with sections of the transfer drawing, by cutting the foreground in Wesleyville: Burning of the Methodist Church, for example, to move it around on the plate and even redraw entire sections.4 To transfer full-scale drawings, Blackwood used a two-step process to press down through the waxy, prepared ground—a substance applied to the surface of the plate that protects it from acid—to reveal the copper surface below.5 First, he used transfer paper layered between the plate and the drawing, going over the lines of the drawing with a pencil to transfer the image onto the hard wax ground. He then went over the transferred lines again with an etching needle to remove a small amount of the ground, exposing the copper surface below.6 In etching, acid is used to “bite” away the lines that are exposed through this scratching, and it is these removed spaces, or “valleys,” that hold ink for printing under high pressure. Blackwood’s process—in which he would apply an acid-resistant ground and then draw through it before the acid etched the plate—underwent many iterations; each one resulted in unpredictable outcomes, such as lines etched more deeply than intended, or “foul biting” wherein acid might penetrate part of the carefully prepared ground. To create tonal areas, Blackwood used aquatint in its traditional form, where powdered resin is applied to the plate and then warmed to adhere the various-sized, scattered particles of resist to the plate before another dip into the acid. After each bath in the acid, he would remove the ground and pull a print from the plate to check its progress. The resulting prints are called proofs or states of a print, and these working proofs give us a glimpse into how Blackwood built his prints.7

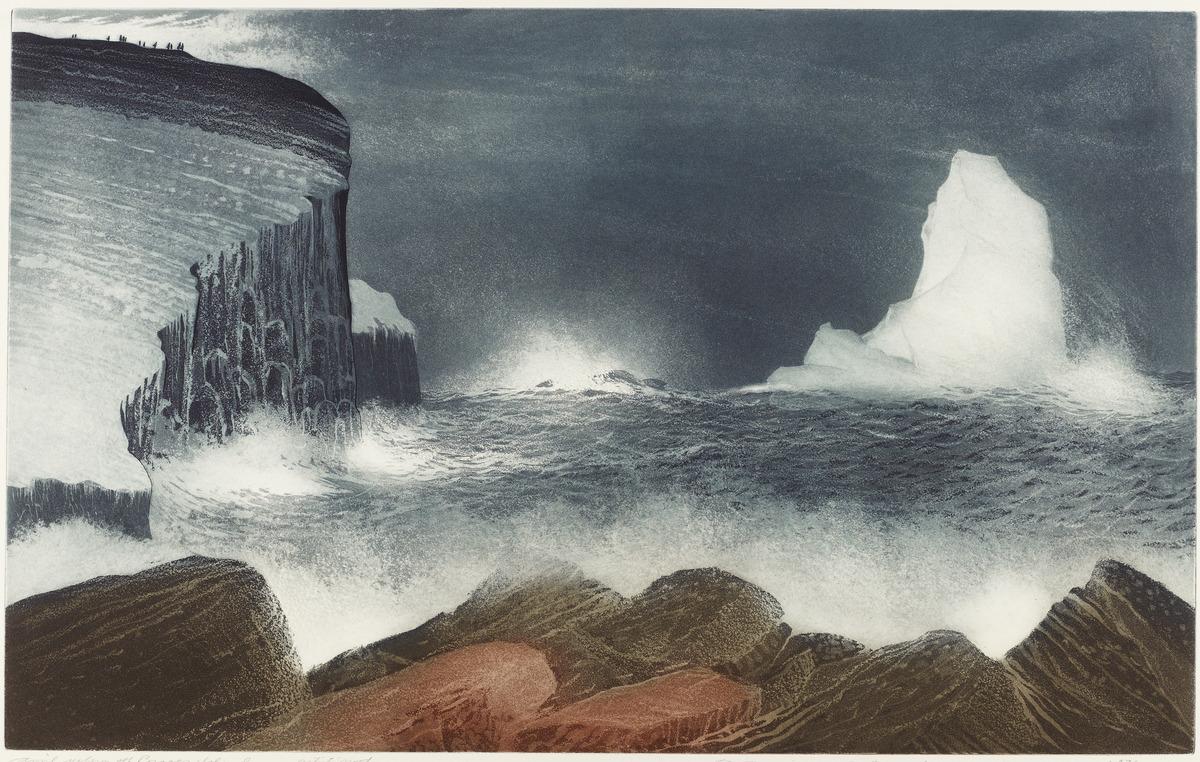

David Blackwood. April Iceberg Off Bragg's Island, 1976. Etching and aquatint on wove paper, Image: 50.3 x 80.6 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of David and Anita Blackwood, 2008. © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO. 2008/273

The experimentation and observation did not end once Blackwood reached the final state of the print. Rather, he often printed impressions in varying shades of grey and blue, or even red, sometimes while seeking the final proof and other times even after he had started editioning a print. This experimentation was part of the process and for Blackwood, that process didn’t have to end with a “final” proof.8 He rarely finished editioning his prints as he insisted on printing them himself, and often he was ready to begin working on another project before completing a full edition.9 He occasionally employed studio assistants part-time, but Blackwood ultimately did all the platework and presswork himself. However, there was one exception.

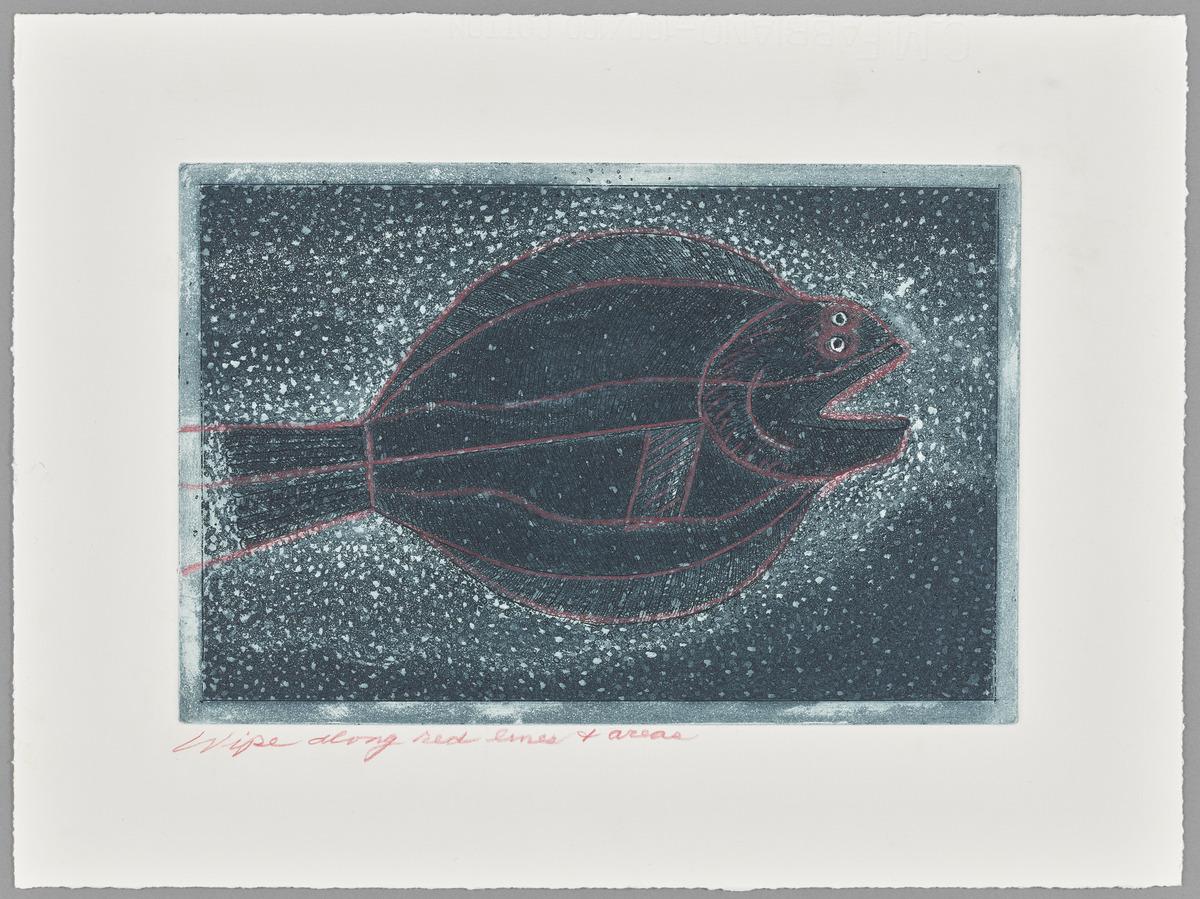

In the last decade of his life, Blackwood allowed a trusted printmaker, Janita Wiersma, to assist him directly in his studio while he recovered from a life-threatening illness in 2015.10 Upon being moved to Toronto’s Bridgepoint rehabilitation facility after a year of hospitalization at Mount Sinai, the artist asked for drawing materials and, soon after, a copperplate and his intaglio tools. The small print Flatty was the result of his first foray back into printmaking.11 A “flatty” is one of four types of fish found in Newfoundland waters, but it is also likely a reference to Blackwood’s much-diminished frame and loss of muscle. Here, the fish acts as a stand-in for an individual so weak that he had to be propped up by pillows in his bed to sit and work. Wiersma worked with Blackwood to realize this print, alongside Anita who brought the plate back and forth between Blackwood’s studio in Port Hope and his room at Bridgepoint in Toronto. Their rich conversations while creating the print together are recorded on various proof states.

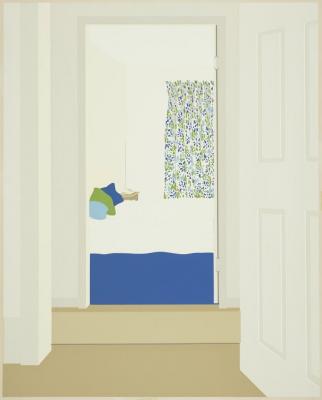

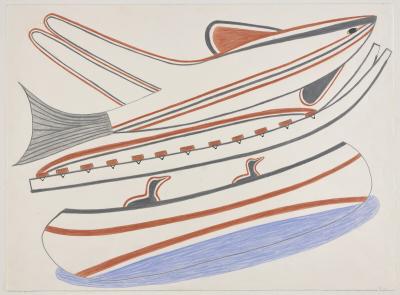

David Blackwood. Flatty, 2015. Etching, aquatint, Plate Mark: 20.2 × 30.3 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario. © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO.

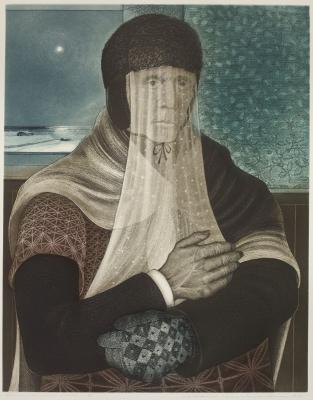

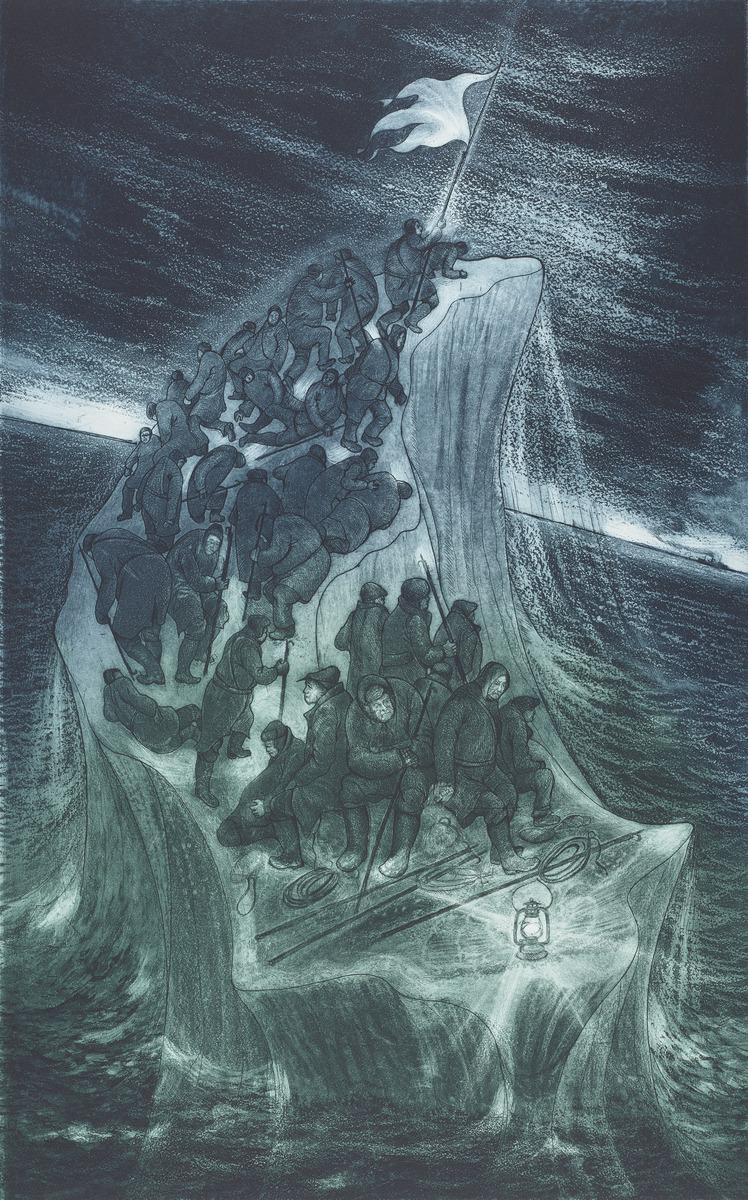

Blackwood never gave up on a print. A plate could have been bitten unexpectedly deep, but instead of walking away, he would return and rework until it met his vision. Once, during a move from one studio to another, he misplaced an unfinished plate from 1970. The work, Search Party: Lost, was subsequently located in late 2019 and finished in March 2021.12 Blackwood began the work in the years following his first printmaking successes and it was part of what would become known as “The Lost Party” series (although the artist did not define it as a set series). In this plate, a group of men cling to an iceberg as they desperately attempt to gain the attention of a ship on the horizon, following Newfoundland’s worst sealing disaster.13 When the work was rediscovered, it existed only as a line etching, and the ship was not yet present on the horizon. It is still unclear why Blackwood subsequently added this tantalizing detail.14

David Blackwood. Search Party: Lost, 1970-2021. Etching, aquatint, Plate Mark: 80.8 × 50.7 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario. © Estate of David Blackwood.

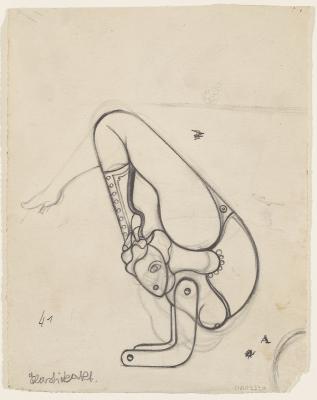

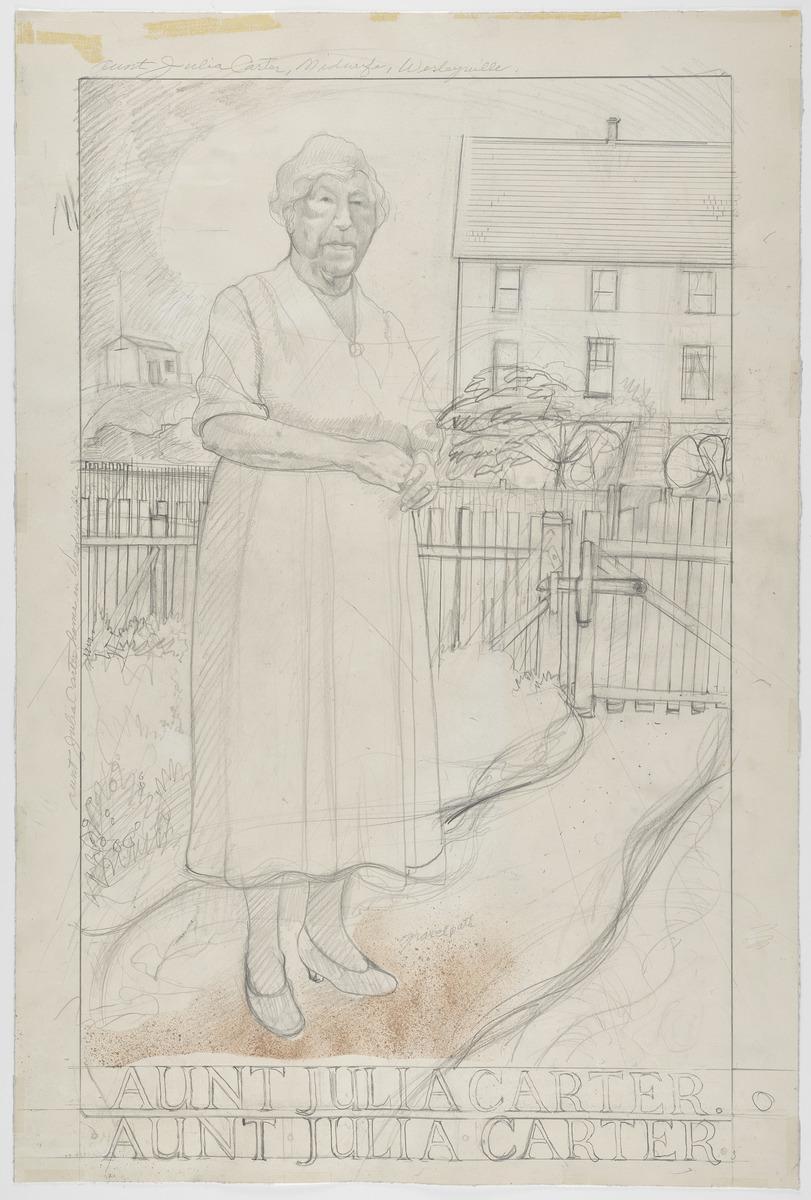

Rooted in the Newfoundland of his childhood, the final print that the prolific artist began prior to his death was an image of Aunt Julia Carter, a midwife in Wesleyville, who delivered Blackwood and many others in the town where he grew up. Extant only as the full-scale outline drawing that he made in preparation for transfer to the copperplate, the work depicts the solid figure of Carter—an aunt not by blood but nevertheless of great personal significance—standing on a pathway leading to a gate in front of her house. For his last planned work to celebrate the woman who guided him into the world is a poignant final expression to leave behind for all who loved the man and his work.

David Blackwood. Aunt Julia Carter, 2020. Graphite, Watercolour, Sheet: 91.9 × 61.2 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario. © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO.

—

This essay is written by Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints and Drawings at the AGO. Purchase the catalogue at the AGO Shop online and in store. The AGO and Goose Lane Editions co-published the catalogue.

The exhibition David Blackwood: Myth & Legend is on view on Level 1 in Margaret Eaton Gallery (gallery 137), Marvin Gelber Gallery (gallery 136), and Betty Ann & Fraser Elliott Gallery (gallery 135). Exclusive Members’ access begins October 8, followed by Annual Passholder and Public Access on October 14. The exhibition is curated by Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints and Drawings at the AGO.

---

-

A technique in which the image is incised into the plate and the resulting recesses are filled with ink. Intaglio differs from the process of relief printing, where the design prints from raised areas.

-

Katharine Lochnan, “Black Ice: David Blackwood’s Prints of Newfoundland,” in Black Ice: David Blackwood, Prints of Newfoundland (Douglas & McIntyre, 2011), 10.

-

David Blackwood in William Gough, David Blackwood: Master Printmaker (Douglas & McIntyre, 2001), 166. The written account of his technique in this catalogue is concise and clear. The National Film Board of Canada made a short documentary in 1976 showing Blackwood working through a plate from start to finish. This film is an invaluable record of both the intaglio process in general and of a particular artist’s masterful use of the technique. See Blackwood, dirs. Tony Ianzelo and Andy Thomson, 1976, National Film Board of Canada, nfb.ca/film/blackwood/.

-

Email from Janita Wiersma, March 5, 2025.

-

Gough, 166.

-

Email from Janita Wiersma, April 23, 2025

-

Blackwood stated that it often took him months to finalize a working proof and copperplate to then print an edition. For example, he noted that he printed his first working proof for Portrait of Heber Field as a Great Mummer on April 26, 2000, and he pulled the twelfth, and final, working proof on October 18. Blackwood in Gough, 166.

-

Email from Janita Wiersma, March 5, 2025.

-

Email from Anita Blackwood, March 5, 2025.

-

Conversation with Anita Blackwood and Janita Wiersma in Port Hope, Ontario, July 20, 2024. Wiersma began working as a studio assistant to Blackwood in 2011.

-

Ibid., August 13, 2024.

-

Conversation with Anita Blackwood and Janita Wiersma in Port Hope, Ontario, July 20, 2024.

-

251 men from two ships died in the tragedy. See Lochnan, Black Ice, 79–80 and 85–95.

-

Wiersma stated that although she and Blackwood did not discuss the ship, she believes it was likely a hopeful sign. Even though the event had occurred more than a century prior, the artist did not want to leave the men lost and without hope. Email from Wiersma, March 5, 2025.