Jerry Ropson’s Video Response to Blackwood

The Newfoundland artist’s video work is on view in David Blackwood: Myth & Legend

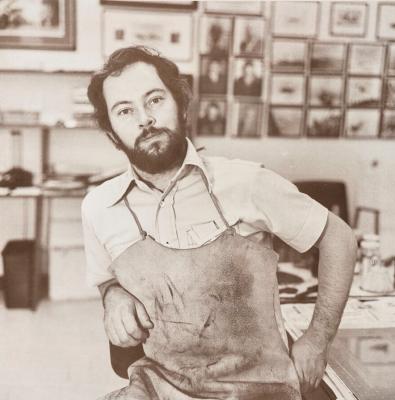

Artist Jerry Ropson with his work, Still.Drift.Return, 2025, commissioned for David Blackwood: Myth & Legend, October 13, 2025 - July 26, 2026, Art Gallery of Ontario. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

Like David Blackwood (1941 – 2022), multidisciplinary artist Jerry Ropson grew up in rural Newfoundland – Pollards Point, to be exact. As an adolescent, his understanding of visual art was largely shaped by the ubiquity of Blackwood’s work throughout his home province. As Ropson developed his artistic practice, his body of work proved to share qualities with that of Blackwood, namely how it aims to document and embody Newfoundland maritime culture. It is only fitting that AGO curatorial staff invited Ropson to create a video work in response to the exhibition David Blackwood: Myth & Legend.

On view in gallery 135 of the exhibition, Still.Drift.Return is a five-minute-long video that hypnotically oscillates between hand-shot footage of Newfoundland’s waters, skies and terrain and home videos from Ropson’s youth. Periodically superimposed over the footage are digital scans of Ropson’s sculptural work, functioning as subliminal iconography that evokes themes of labour and survival. To accompany the montage, Ropson constructed an original ambient soundscape, consisting of his own field recordings taken while visiting Newfoundland in recent years. While viewing David Blackwood: Myth & Legend, visitors are encouraged to sit down and experience the video as a complement to the exhibition.

Ropson is a multidisciplinary artist working in video, sculpture, installation and performance. His work has been exhibited widely across Canada for over two decades. Ropson recently spoke to Foyer about rural Newfoundland, Blackwood’s legacy and the creative process behind Still.Drift.Return.

Foyer: How did you understand and engage with Blackwood's work growing up in Newfoundland? How would you describe the place that he holds in the culture?

Ropson: I grew up in rural Newfoundland, in a place with roughly 400 people and very little access to visual art. If anything, the mediums of art that were more present in the community were theatre and music, and not in a professional sense, more like skits and performative storytelling. I came from a family of storytellers, and I was always interested in storytelling as a child.

David Blackwood’s work, however, was ubiquitous throughout the whole province. Growing up in rural Newfoundland, you can’t escape it. My family was working class, and no one in my household collected art, but if I ever went to a teacher’s house, for example, they would have a Blackwood print. As I got older, became more curious, and began seeking out visual art, he was the first artist I could name. His work was so omnipresent that it was on the cover of one of our school textbooks. There were other Newfoundland artists I could name – like Mary and Christopher Pratt – but David Blackwood was the first visual artist whose work I could identify with. I knew the stories he depicted and the places they happened. I was also drawn to the dark, haunting quality of his work.

When I was in high school, a teacher of mine encouraged me to apply to art school and helped me put together a portfolio. When I was accepted, she gifted me a sketchbook and tucked within its pages was a postcard with a Blackwood print on it. I’ll never forget what she said to me: “This is my favourite artist. Now, it's your job to become my new favourite artist.”

The film features original ocean footage, home videos and various graphic iconography. Can you walk us through your creative process and describe what you were trying to achieve?

I wanted to make a video that not only engaged with the language of Blackwood – and the myth-making of rural Newfoundland – but also served as a meditation on the idea of surfaces.

I think about the video as my meditation on surfaces: the surface of the ocean, the surface of the plates in Blackwood’s printmaking process. I was thinking about images being etched into copper, and the idea of image reversal when a print is made.

I asked myself: “What if I could create a video that speaks to the language and history that Blackwood evokes, but also is in conversation with the process of printmaking?” I also wanted it to feel intentionally ambient. In my opinion, people rarely sit and watch video art at a gallery. I wanted this work to blend and co-exist with the exhibition and invite people to be drawn in at various points throughout the video. I usually resist the inclusion of figures in my work, but I felt it was important to add them to this project because figures are central in Blackwood’s work, and it’s a great way to draw the attention of viewers throughout the video.

The icons that flash are scans of sculptures that I’m currently working on. They are woodcarvings and textile weavings that I digitally scanned and edited in Photoshop. They come from a project I’m currently working on about the loss of cultural knowledge in our current era.

Can you describe the elements of your original soundscape and what went into building it?

Sound was an important aspect of this project for me from the very beginning. I wanted the sound to reference all the things I mentioned earlier about process and making, but it was also an opportunity for me to include sounds from my vast archive. Each summer when I return home to rural Newfoundland, one of the things I do habitually is record sounds on my phone or a digital recorder. There were many sounds sitting in my archive that I didn’t know what to do with: me and my uncles sitting on a boat, drinking in a shed with family members, community meetings and more. This video gave me an opportunity to return to these sounds.

Aside from one moment in the video when something is being pulled from the water, none of the sound is linked to the video. I removed all the sound from the source video and layered in my own sounds and my own voice. In my own practice, I often hum when creating work. It’s something I’ve always done. While at the Banff Centre this summer, I recorded myself humming in a silo. I used it this in the video, to include some reference to my own artistic process. In keeping with the nautical theme, it almost sounds like a foghorn.

I built the soundscape by working in the program Audacity, layering sounds from my own archival process: humming, boats in the harbour, water hitting the shore, a drone sound, urinating into the ocean, and much more from my rural archive.

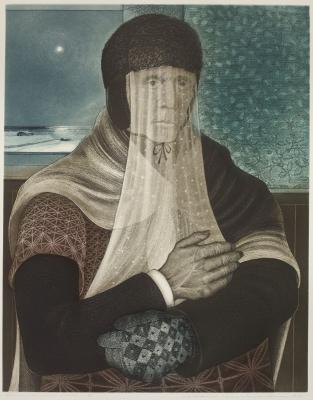

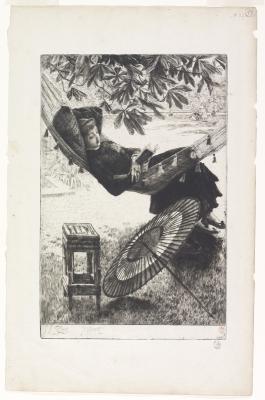

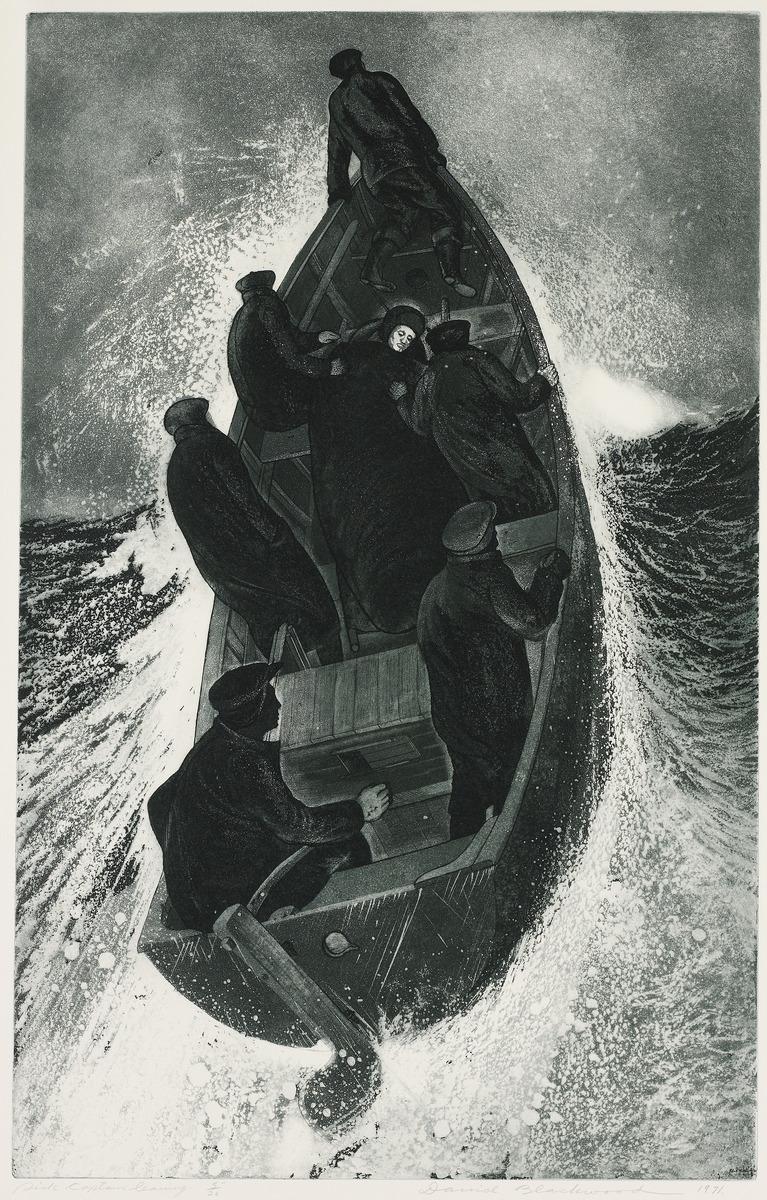

David Blackwood. Sick Captain Leaving, 1971. etching and aquatint on wove paper, Image: 80.5 x 50.4 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of David and Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario, 1999. © Estate of David Blackwood. Photo: AGO. 99/923

Were there any works that you focused on in your response to the exhibition? Do you have any favourite works from the exhibition?

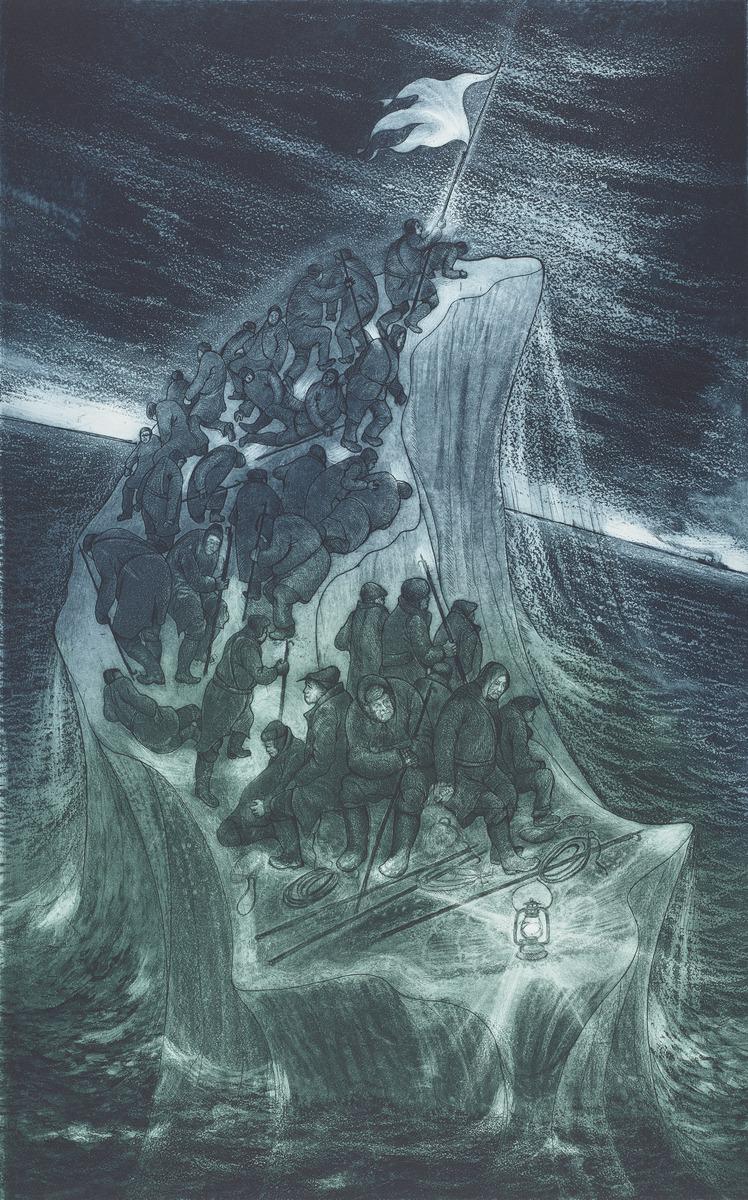

There were many works I held in mind while making the video. So much of Blackwood’s practice is rooted in specific visual references to place, and I found myself re-positioning or embodying those references through my own footage. But when it came to the prints themselves, the strongest influence was on how I was thinking about space while editing, particularly the footage of the ocean’s surface. I kept returning to the way Blackwood depicts boats on the water, how he captures that distinct sensation of being in a small boat during rough seas, the vessel tipping up on end, the horizon shifting uncomfortably. It’s such a singular way of approaching the depiction of the ocean. Because much of my own footage was shot from a small fishing boat, both the source material and the theme felt closely connected. One image I returned to often was Sick Captain Leaving (1971). It was exciting to see that the composition spatially echoed in another work, Search Party Lost (1970–2021), featured in the exhibition.

David Blackwood. Search Party: Lost, 1970-2021. Etching, aquatint, Plate Mark: 80.8 × 50.7 cm. Promised Gift of Anita Blackwood, Port Hope, Ontario. © Estate of David Blackwood.

Some of my favourite works in the exhibition, though, are the images of Ephraim Kelloway’s Door — both the prints and the frottage. I’ve always been drawn to the fact that Blackwood returned to that shed door repeatedly throughout his career, creating multiple prints and paintings of it. There’s something compelling about the way the door changes over time, how he documented its weathering and continued use. That sense of accumulated history, of objects bearing the marks of labour, of care, of time... is something I think about often in my own practice, especially in relation to the materials I collect, make, and work with.

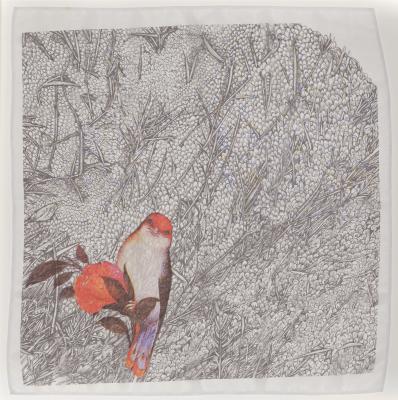

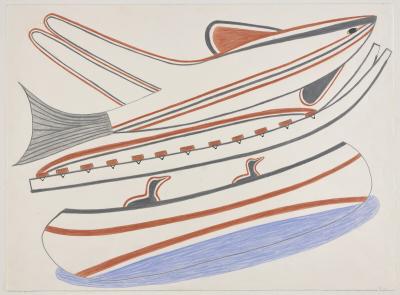

David Blackwood. Ephraim Kelloway's Door, 1982. etching and aquatint, with hand-colouring on wove paper, Image: 80.9 x 50.4 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of David and Anita Blackwood, 2008. © Estate of David Blackwood 2008/289

Still.Drift.Return is part of the exhibition David Blackwood: Myth & Legend, on view now on Level 1 of the AGO. The exhibition is curated by Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints and Drawings at the AGO.