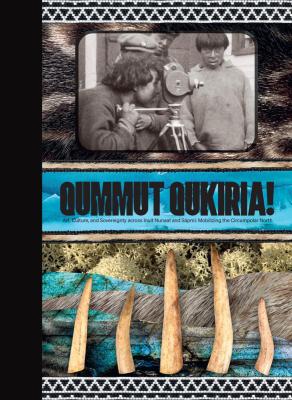

A Q&A with the editors of Qummut Qukiria!

The collection of 38 essays charts the exponential rise of Inuit and Sámi voices in art and culture.

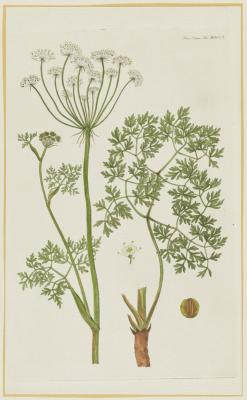

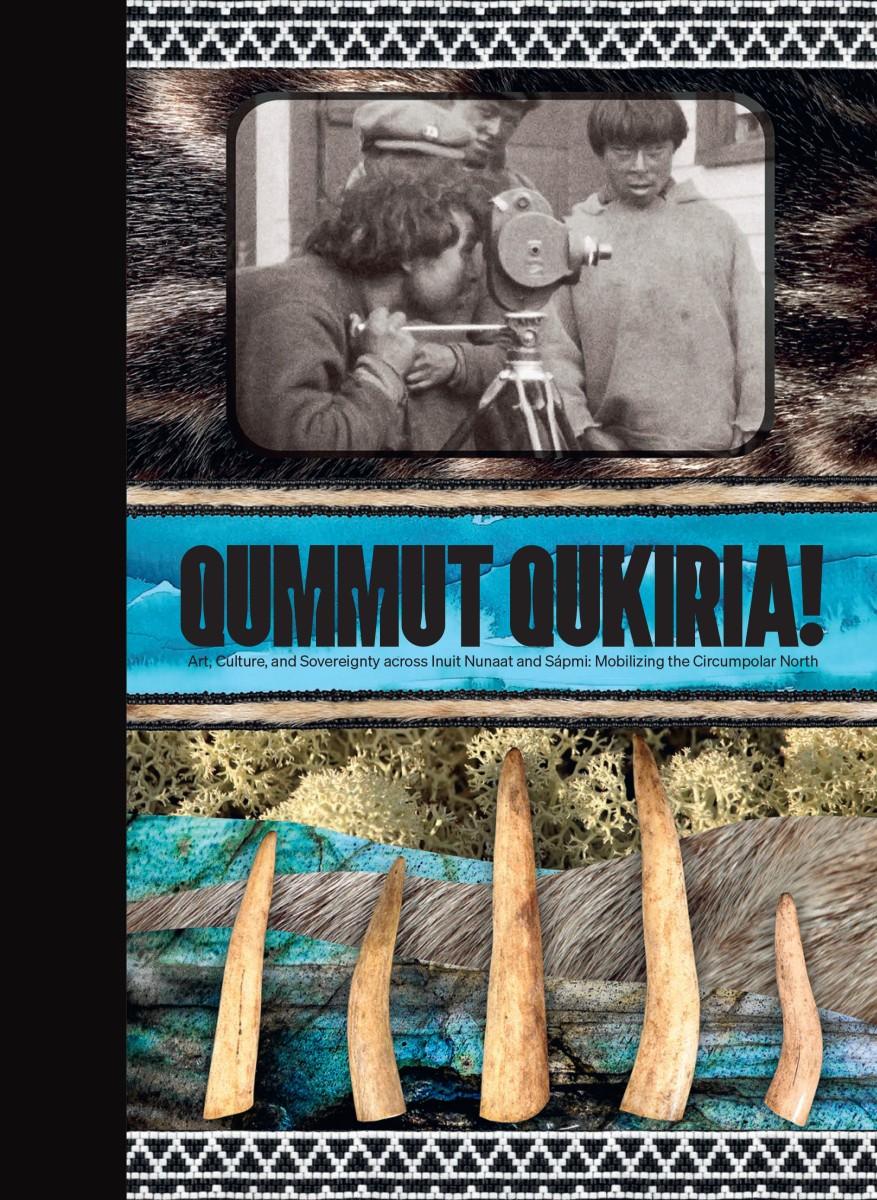

Glenn Gear, 2020. Digital collage of archival photography and found objects. Commissioned by Inuit Futures in Arts Leadership: The Pilimmaksarniq/Pijariuqsarniq. Qummut Qukiria! Art, Culture and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North Cover

What will be the impact of Inuit and Sámi art and curation on our collective future? Who are the artists, curators, writers, filmmakers, activists, students and scholars engaging in that conversation within and beyond the Indigenous homelands of the circumpolar North? One fascinating volume of 38 essays begins to answer these questions and more, as edited by scholars and curators Anna Hudson, Heather Igloliorte and Jan-Erik Lundström.

Qummut Qukiria!, “up like a bullet,” puts on record the “exponential rise of Inuit and Sámi voices and cultural worldviews” in the face of “climate change, resource extraction and Arctic development.” The contributions are resonant and wide-ranging, weaving traditional practices with contemporary art forms originating from Inuit Nunangat, Kalaallit Nunaat, Sápmi, Canada and Scandinavia. Included are entries from artists like ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, along with Taqralik Patridge, AGO Associate Curator, Indigenous Art - Inuit Art Focus and Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator, Canadian Art. In addition, ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk’s video installation Silaup Putunga (2018) - on view now at the AGO - is highlighted in the book.

“Qummut Qukiria! is an incredible and broad introduction to contemporary Inuit, Nunaat and Sápmi art and ways of being,” says Olivia Mikalajunas, the book's editorial assistant. “It brings to light discussions happening in the here and now, in the North and South alike. There is a lively nature to this book, with different voices illustrating vast, ever-moving conversations.”

Hudson, Igloliorte and Lundström shared what went into bringing Qummut Qukiria! to life on the page.

Foyer: This book is a massive, collaborative undertaking and a global venture connecting Indigenous Circumpolar peoples. For those who have yet to pick up a copy, what brought the three of you together as editors? When and how did things take off for the book?

Hudson: Heather and Jan-Erik were key team members of the project Mobilizing Inuit Cultural Heritage (MICH), that I ran at York University for seven years. Each of us built upon our existing networks and contacts through local, Canadian Arctic and circumpolar collaborations. The book documents the excitement of Inuit and Sámi artists, scholars and curators for Indigenous expression. Qummit Qukiria! – up like a bullet – attests to cultural richness and resurgence as a beacon of hope and leadership amidst circumpolar climate change. The AGO was an incredible museum partner in MICH, which the book also records.

Foyer: And now that the book is out in the world, what are your hopes for it?

Igloliorte: I’m thrilled for Inuit and Sámi audiences – especially students, scholars, curators, museum staff and directors, artists and community members, our biggest stakeholders – as well as all curious readers, to engage with what we’ve collectively created together, and to learn about all the intertwined research projects, exhibitions, stories and exchanges that make up the many and various contributions to the book. There are scholarly articles, photo essays, artistic responses, personal reflections and more included in Qummut Qukiria!, but it all fits together beautifully I think because it reflects the holistic nature of Indigenous life. We don’t, you know, do our work over there and then make art over here, or think of our time on the land differently than our time-sharing food or learning a new skill or attending a conference; it’s all connected, every experience is connected and informs all of our practices. So while we have grouped all of the contributions carefully together through several big thematic section headings - Land and Language, Decolonial Practices, Community and Sovereignty, Circumpolar Resurgence - we want to note that almost every essay intersects meaningfully with other thematics in the text (and we long debated what should go where!) I hope readers make whatever connections are useful and meaningful to them as they read through the books and find their own interesting takeaways from all of the wonderful contributions.

Máret Ánne Sara, Pile o'Sápmi, Deatnu/Tana, 2016. Two hundred raw reindeer heads, one Norwegian flag. © Máret Ánne Sara. Photo by Iris Egilsdatter.

Foyer: Tell us about your choices for the book's cover and endpaper, which feature art by Glenn Gear, Máret Ánne Sara and Julie Edel Hardenberg.

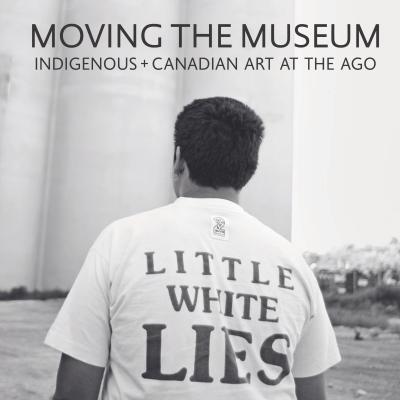

Lundström: The commissioned cover, by Glenn Gear, and the endpaper artworks, by Máret Ánne Sara and Julie Edel Hardenberg, embracing the Indigenous geographies of Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi, were wonderful opportunities to extend and lend further impact of Qummut Qukiria! Both cover and endpaper works are deeply integrated with the book’s weave of thematics – Máret Ánne Sara´s indictment of the struggle with colonial state authority, Julie Edel Hardenberg’s meditations on the flag of Kalaallit Nunaat, and Glenn Gear’s spectacular collage, made for the book, juxtaposing Inuit cultural artifacts with a politics of (self)representation.

Foyer: The introduction starts with discussing the notion of the global Indigenous turn, or “local turn,” that extends to art and culture. Jan-Erik, you chose to describe it more as a resurgence. Can you share your thoughts about the moment we find ourselves in and why it needs to be documented now in book form?

Lundström: As a catchphrase for increased attention given or various venues and platforms for art and culture made available globally to Indigenous art and cultural production, the “global Indigenous turn” (or “local” if we wish to stress the grounded element – the consistent relation to land – of all Indigenous activities) serves to alert to this real phenomenon. And, of course, we applaud and savour this moment of change, imagining and offering Qummut Qukiria! as born out of this. But the qualification resurgence adds, I believe, the recognition that as a cultural uprising, emergence, or turn, this present-day turn is not unprecedented in the sense of a resurgence. There have been uncounted resurgences, resistances, etc., in the past. In fact, decolonial practices, as one of the sections of Qummut Qukiria!, Explicates, begins with colonial practices, which have existed as long as coloniality. Furthermore, there is skepticism towards the terminology of “turn” or “wave,” in its temporal sense, as if it were a passing moment, a phase, a trend soon to be replaced by another trend, while I’d suggest that what Qummut Qukiria! articulates is transformation, and change, pedalled by yet more resurgences.

Foyer: A glossary foregrounds the book with shared words from the Inuit, Sámi, Greenlandic and non-Indigenous contributors featured. Can you share why the glossary was essential and presented this way? What considerations were made for what words were and were not included?

Hudson: We combed through all the essays for keywords. The idea was to ensure the book acknowledged Indigenous languages and dialects as the foundation of identity and respected the fact that for most of the contributors, English is a colonial language. The keywords provide a snapshot, if you will, into linguistic perspectives on our themes of land, decolonization, community, sovereignty and resistance. The repetition of ideas and concepts across languages and dialects also indicates connection and cohesion across geographies which blur nation-state borders. Shared language creates community. For readers, keywords are empowering and change-making.

Qummut Qukiria! Art, Culture and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North, page 20

Foyer: A question for each of you: Of the many contributions included, which one has been the most impactful for you and why?

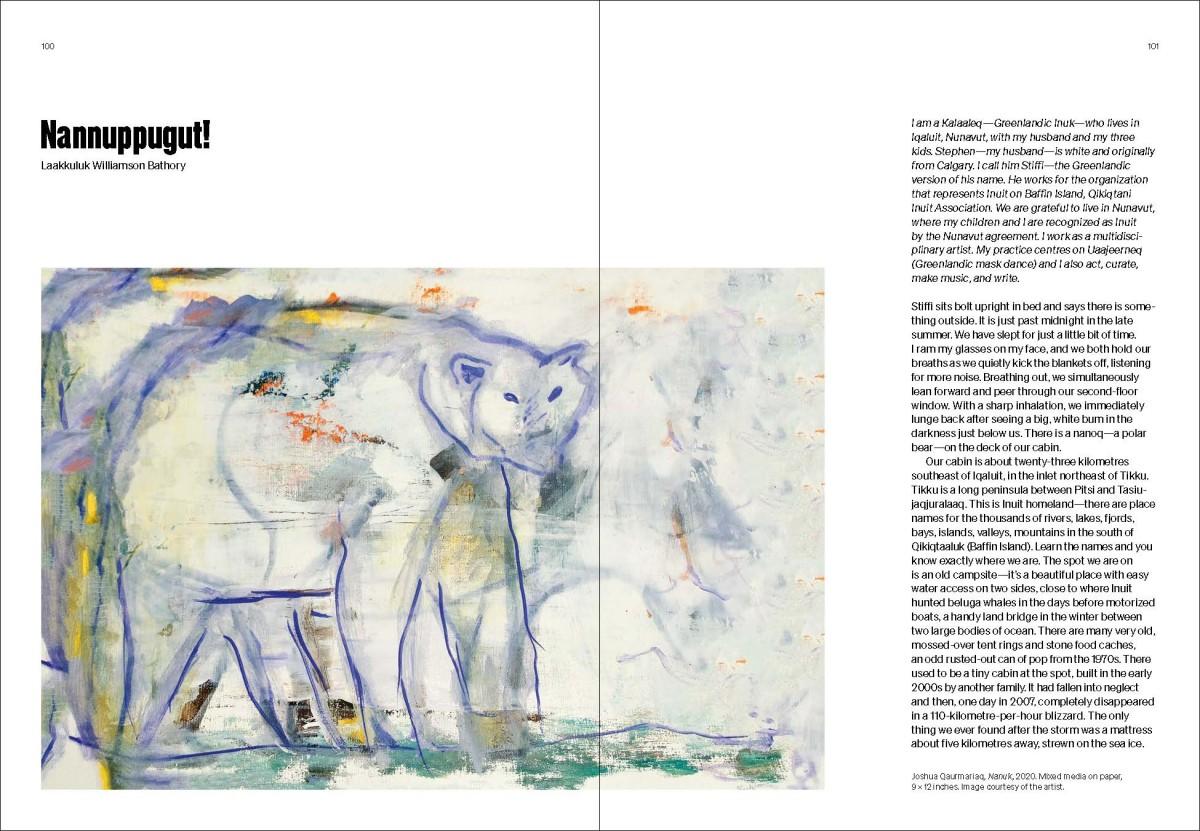

Igloliorte: Oh, it is so hard to pick just one, as I find each chapter interesting, useful and creatively and intellectually stimulating in a different way. Methodologically, I found Anna's interview with Anne Lajla Utsi and Liisa Holmberg very inspiring. It focused on the Sámi Film Institute’s innovative strategy for supporting Sami filmmakers during the global pandemic by funding fifteen short films that could be created under COVID-19 restrictions and then sharing them on the ISFI’s online platform. They were the funders of the project, but they also learned how to be better supporters of Sami filmmakers through implementing the project, which I found fascinating and instructive. I also deeply appreciated all the curatorial essays because they have helped me deepen my own curatorial practice and ways of thinking about exhibition creation. But perhaps I was most impacted by ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory’s essay, Nannuppugut!, because of how it so vividly illustrates the connection – and separation – we have as humans from our non-human relations in the Arctic. Polar bears have their own ontology of the world, and in their worldview, humans are not centred. When ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk describes the moment of coming face to face with a Nanoq as she leaned out the window of her cabin, she describes how she sees the thought flash in the bear's eyes, “so this is human.” In that moment, ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk reflects, “she has never had to fear a thing in her life, and she studies me with a type of intelligence I can only grasp at understanding,” adding, “in the midst of this moment, I feel my humanness and the nanoq feels her nanoqness, and each of us recognizes that even though our worlds are now touching we are completely separate beings.” This moment of stillness and co-recognition in an otherwise harrowing and heart-wrenching narrative has stayed with me.

Qummut Qukiria! Art, Culture and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North, page 7

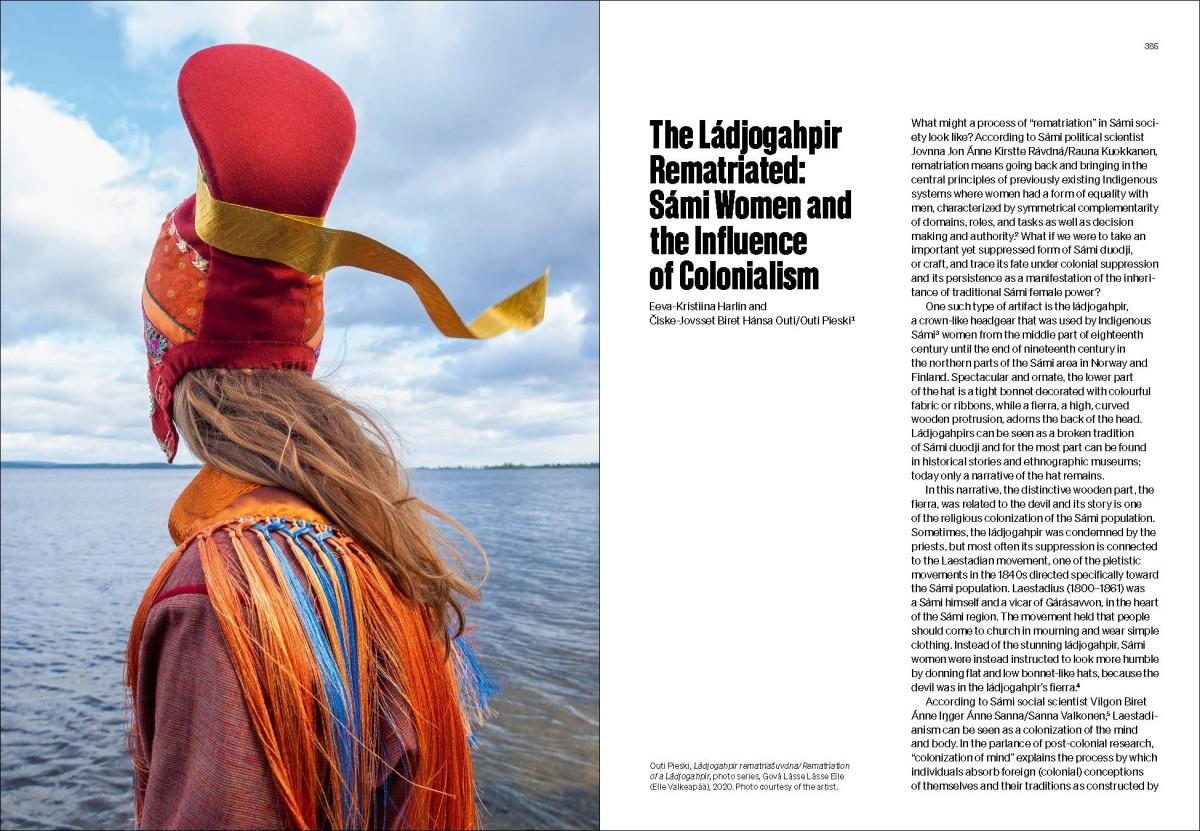

Lundström: Impossible question, indeed. Affirming all of Heather’s suggestions, I was much moved by several contributions delving into both disquieting and restitutive experiences of language loss and language revival, such as Sigbjørn Skåden’s father-and-son story or Julie Edel Hardenberg’s retelling of the continued suppression of Greenlandic in Greenland. The story of the revival of the ládjogaphir, the Sámi women’s hat, is such a phenomenal story of rebirth, reskilling and rectification, interweaving with such precision issues of gender and spirituality with coloniality. I was also much privileged, in my own contribution, to be able to encounter and share with the book’s readers the extraordinary work of several generations of Sámi visual artists. Finally, the various contributions engaging with Indigenous curating from different perspectives, including colleague editor Heather’s contributions, were very, very rewarding and pave the way for future work.

Qummut Qukiria! Art, Culture and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North, page 19

Hudson: Heather and Jan-Erik capture our happy dilemma well. The book works holistically as an acknowledgement of Inuit and Sámi individual and community voices, as well as Indigenous and settler dialogue. Heather’s SakKijâjuk essay breaks new ground for the appreciation of art in Nunatsiavut, and Jan-Erik provides an unprecedented history of contemporary art in Sápmi. And I remain so moved by ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk’s story of the polar bear, and the image of her daughter’s small hand on the giant paw. The collaborative contributions of Taqralik Partridge and Nils Ailo Utsi are equally arresting and profound.

Foyer: The notion that exhibitions are investments in culture comes up in the book with Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak at the AGO cited as a recent example. Looking towards the future, what do you want to see more of and less of when exhibiting circumpolar Indigenous art in museum and gallery spaces?

Lundström: As the book’s discussion of, for example, SakKijâjuk so precisely manifests, exhibitions of introduction and overview have successfully been made, and now we look forward to novel curatorial practices. I look forward to exhibitions that complicate heritage and history and that, at the same time, can bring on board and weave together many of the challenging parameters of the present – intercultural encounters, hybrid spaces, climate crisis, the crisis of democracy, furthering decolonial work and more.

Hudson: There’s no turning back from Indigenous-curated exhibitions of Indigenous art and culture. As Jan-Erik notes, new ways of curating, defining curation and museum practice are emerging … leading us back to the question: What will be the impact of Inuit and Sámi art and curation on our collective future?

Qummut Qukiria! Art, Culture and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North, page 17

Qummut Qukiria! Art, Culture and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North is out now. Order your copy from Goose Lane Editions here or pick it up from shopAGO.