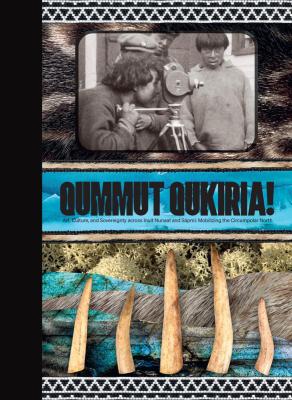

Joyce Wieland's Lens on the Arctic

AGO Curator Georgiana Uhlyarik writes about Wieland’s trailblazing legacy

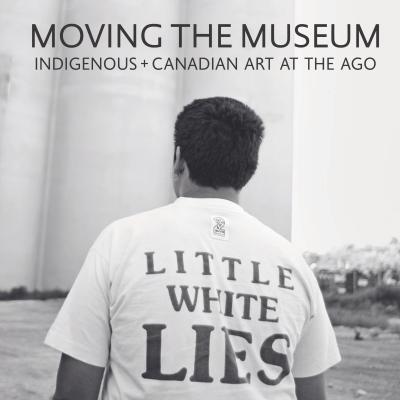

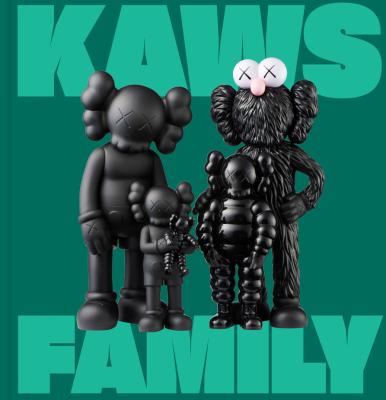

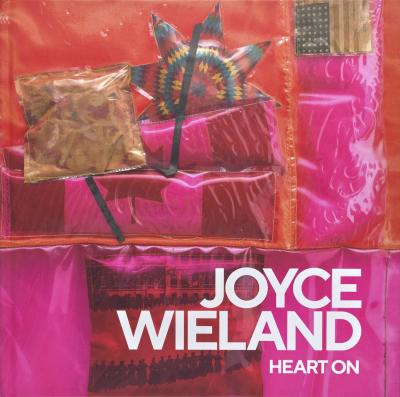

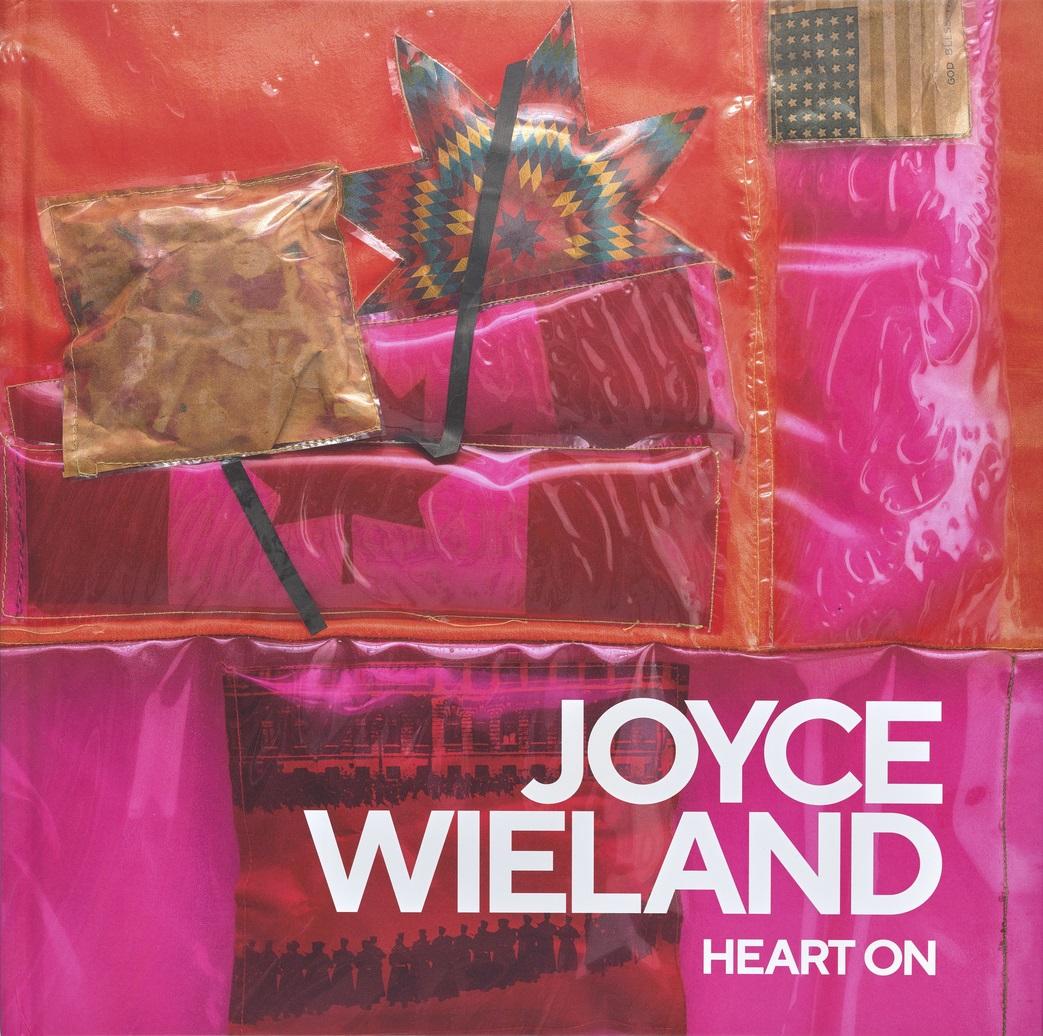

A new publication celebrating the life, art, and legacy of Toronto-born artist Joyce Wieland has recently been published. Joyce Wieland: Heart On is a 288-page exhibition catalogue that accompanies the first major retrospective of Wieland’s work since 1987, highlighting over five decades of radical artmaking across textiles, collage, print, drawing and film. The exhibition is co-organized by the AGO and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art at the AGO and Anne Grace, Curator of Modern Art at the MMFA.

To delve deeper, we turn to an excerpt written by Uhlyarik.

Facing North

Among the principal subjects in Joyce Wieland’s work over her five-decade career, the least discussed is the Arctic.1 The “North” is a subject she returned to repeatedly during the 1970s, in an impressive range of media, to create some of her most well-known and ambitious works. Yet she was rarely asked about it directly, and spoke of it only in passing a handful of times. There are scarce traces of the Arctic in her archives, making it difficult to understand her source materials, or to confirm when she visited Kinngait, Northwest Territories (now in Nunavut), and how many times. It is—perhaps as it should be—only through the works themselves that the Arctic reveals itself as an intricate, persistent, and powerful theme for Wieland. Her perspective is at once progressive and original, as well as complicated and limited by her position as an anglophone in southern Canada.

Wieland’s notions about the region are shaped by a complicated love for her country. In her work, the Arctic of her imagination is bountiful, full of colour and life, and under attack.2 She idealizes the Arctic as “the true north” symbol of Canada—and thus assimilated into Canada’s national identity—yet her artistic contribution to “the idea of North” and its representation is far from a common stereotype. As cultural critic Susan Crean argues, “Wieland uses the trappings of Canadianism with unashamed love yet without sentimentality, as no one else has done.”3 The Arctic is a predominant theme in her landmark True Patriot Love / Véritable amour patriotique exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) in the summer of 1971, with some aspect of the Arctic featured in nearly a quarter of the works included.4

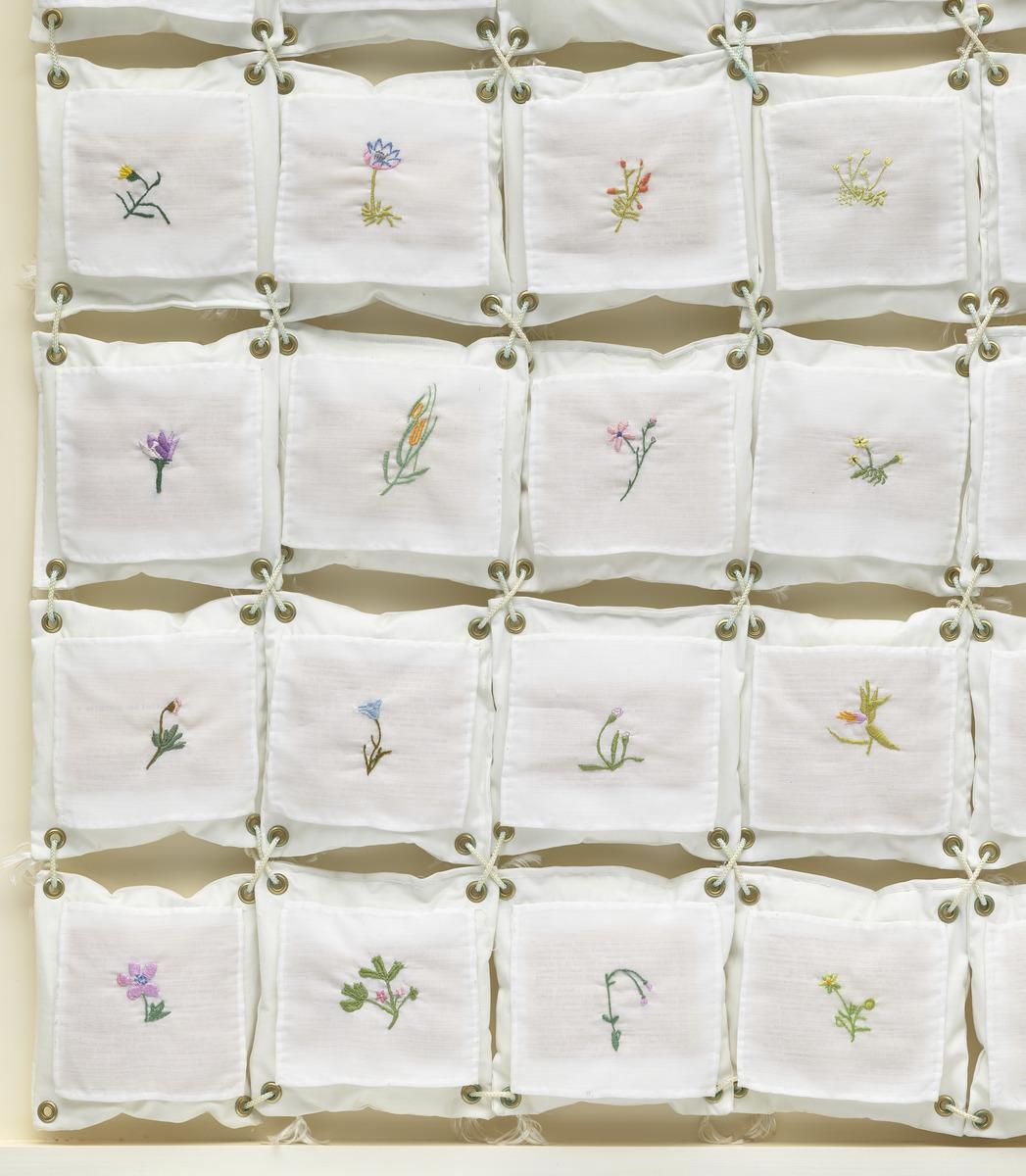

‘Water’ quilt, 1970–1971, contains and is composed of 60 pages from James Laxer’s The Energy Poker Game photographed on cotton, mounted on 60 cotton pillows (with brass grommets in all 4 corners. Veiled by 60 Arctic flowers embroidered on cotton). “To believe in nature was to rebel”

– Thoreau 5

This is how Wieland introduces one of her signature textiles in the artist book accompanying the exhibition. Further down the page she indicates that each six-by-six-inch “pillow” is to be “tied through” with “sailor’s rope” in order “to hold ‘Water’ Quilt together.” The final work is comprised of sixty-four rather than sixty “pillows” arranged in a square grid, framed, glazed, and hanging on brass hooks through the sixteen grommets at the top. Despite its title—the only one of Wieland’s works to include the word “quilt”—it makes for a rather inadequate blanket, and there is no depiction of water, unless we imagine the plain white cotton support as snow.

Joyce Wieland. The Water Quilt (detail), 1970-1971. fabric, embroidery thread, thread, metal grommets, braided rope, ink on fabric, Overall: 121.9 x 121.9 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase with assistance from Wintario, 1977. © National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: AGO 76/221

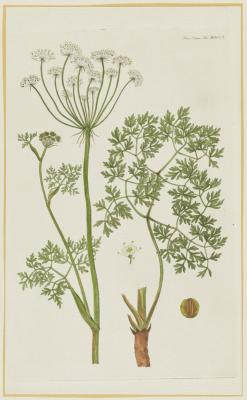

The Water Quilt is a conceptually arranged field of delicately embroidered flowers: a composite arctic landscape, deceptively serene and disquietly indexical. Each cotton square is a portrait of an arctic flower and its leaves, small, expressive, and singular.6 Wieland found them illustrated and described in a government-funded bulletin documenting “the 340 species and major geographical races of flowering plants and ferns that comprise the vascular flora as it is known at present of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.”7 (This is the book she took apart, altered, and reassembled at her kitchen table in New York in order to create her exhibition publication.8) It includes black-and-white botanical drawings with scientific descriptions of each plant, including the colour of the flowers and shape of leaves and stem. While the book is an empirical guide praised for advancing scientific knowledge of the archipelago, Wieland’s composition frees the flora from the imposed botanical classification and instead presents the plants in a colourful array suggesting an alphabet of nature. The sixty-four flowers are an expression of the fertile and diverse vegetation of the Arctic, in extraordinary contrast with the common southern misconception that the region is barren, bleak, and inhospitable.

Joyce Wieland. The Water Quilt (detail), 1970-1971. fabric, embroidery thread, thread, metal grommets, braided rope, ink on fabric, Overall: 121.9 x 121.9 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase with assistance from Wintario, 1977. © National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: AGO 76/221

Wieland’s intention is not to be descriptive or instructive. Rather, she seeks to create an aesthetically compelling vision out of very ordinary—“innocent”—themes, as she once described them.9 In The Water Quilt, Wieland takes something as familiar and overlooked as an embroidered flower and imbues this traditionally decorative motif with agency and meaning. The flowers are small yet they spread into an immersive composition that draws in the viewer. Up close, the individuality of the careful stitching coveys the lively personality of each plant. These are no ordinary blossoms. Wieland’s beautiful, graceful flowers thrive in the far north. Indeed, to believe in nature is to defy convention, to rebel.

Beneath this cover of resilient innocence is Wieland’s active rebellion. “There is Art and there is Politics, and I have been working on putting them together in aesthetic terms for years,” she said in 1974. “I think one can have all the thrill of doing art as well as embedding the political thing in it—inside it.”10 Veiled, yet noticeable under each flower, is a page from political economist, historian, and activist James Laxer’s The Energy Poker Game: The Politics of the Continental Resources Deal, published in late 1970. “A beautiful way to hide something terrible,” she said.11 This is the anti-government “bulletin” Wieland favours and lists first in her description of The Water Quilt. Laxer’s is a passionate and informed political guide raising awareness of the threat presented by the American “corporate and military empire” extending its reach to extract and deplete Canada’s natural resources.12 “There is little doubt that once the U.S. successfully gains access to our oil and natural gas on its terms, it will turn to our water,” he writes in a chapter dedicated to water, “the ultimate energy resource.”13 Outlining the complicity of Canadian politicians (with then–prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s face as the Joker on the cover), his book is an appeal to “resist the energy deal” as it was being negotiated at the time. The Water Quilt is Wieland’s artistic response to Mel Watkins’s call in the introduction: “We will be armed with this book. Read it and join us.”14 There is no comfort to be found in Wieland’s “quilt.” The sailor’s rope that binds it can come undone. The threat of ecological devastation is imminent. She makes her call to action more explicit in the companion quilt, Arctic Day (1970–1971).

Nearly two-and-a-half metres in diameter, Arctic Day suggests a stylized view of the world from above the North Pole. Comprised of over 160 circular cushions of various sizes gathered together in a large round frame, this work implies a circumpolar view of the Earth as well as a magnified view of multiplying cells in a Petri dish: life!15 Wieland breathes vibrancy into this grand white tondo, imbuing it with an inner glow produced by the bright colour fabric sewn on the back of the cushions.16 “I am trying to give the illusion of shadows on the snow with my Arctic Day,” she declared while she was making it.17

Like The Water Quilt, it plays with scale and invites close looking. As the viewer draws near, Arctic Day reveals the diverse ecosystem of the region. With coloured pencils, Wieland has drawn individual portraits of arctic flowers, mammals, birds, and insects in their habitat, along with icebergs and the land. Each textile drawing is sewn to the front of a cushion. She identifies a few, such as the great black-backed gull and willow ptarmigan. Wieland conducted extensive research “about the animals, the insects, the flowers of the Arctic” to create these drawings.18 Just off-centre and above is a caribou, with a warning over its majestic antlers. As though puffy clouds have aligned to deliver a message, it reads: DECLINE OF THE CARIBOU. As Wieland stated, she was in “a panic; an ecological, spiritual panic.”19

Arctic Day marks Wieland’s first use of coloured pencils, the small, round format, and delicate drawings of animals to which she returned nearly a decade later in her The Bloom of Matter series.20 In this work she plays with the simplicity and directness found in schoolbook illustrations to convey the interconnectivity of life in the polar region and communicate her urgent ecological message. “The land which we all count on, that we keep counting on, suddenly we look up and what has happened, it is all churned up, like the James Bay [P]roject.” By 1971, Wieland was increasingly aware of the Cree and Nunavik Inuit fight against the Quebec government’s plan to build a hydroelectric dam on the east coast of James Bay—the largest construction project in North America—which would devastate the caribou and Indigenous communities. Galvanizing the arts community, Wieland was politically active, participating in raising awareness against the project. In her political poster for a fundraiser featuring Waskaganish Cree chief Billy Diamond (1949–2010), she was unequivocal and incendiary, calling Quebec’s plans “a deadly nightmare” and citing “a plot of cultural genocide.”

Through her art, Wieland deftly embedded her politics into her aesthetics. “If you are trying to express something which hasn’t been said before, it might require finding other ways—a new form of expression.” Her pair of soft Arctic landscapes, The Water Quilt and Arctic Day—a square grid of embroidered flora and a composite circle of drawn fauna—convey a southern vision of the Arctic without precedent in Western art. As art critic Hugo McPherson (1921–1999) wrote in 1971, “This is Wieland’s great pastoral of the north . . . it renders lovingly the details of an ecology that is almost unknown in the south.”23 These works are comparable in their ambitious size and scope to the celebrated paintings of icebergs, frozen landscapes, and aurora borealis by Fredric Edwin Church (1826–1900), Rockwell Kent (1882–1971), Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970), and other Group of Seven members, as well as Doris McCarthy (1910–2010), Wieland’s teacher and mentor. These artists travelled to the Arctic on government and scientific expeditions and returned to their studios to produce sublime images of empty landscapes and ice. Their paintings shaped a southern notion of the Arctic as mystical and remote.

Wieland absorbed this tradition while growing up, and as an artist. Through her Arctic Day drawings and her resolve to glorify embroidery and quiltmaking, she is not defying her artistic heritage, rather she is advancing a new “language of emotions,” as Leila Sujir calls it—an Arctic imaginary all her own.24 “You work on your own myth from the very basic things you have around you.”25 Wieland’s intention is to awaken southerners to mobilize and defend the environment.

—

This excerpt is written by Georgiana Uhlyarik, the Fredrik S. Curator of Canadian Art and Co-Lead of the Indigenous + Canadian Art Department at the AGO. To read the full essay, purchase the catalogue at the AGO Shop online and in store. The AGO, MMFA, and Goose Lane Editions co-published the catalogue.

The exhibition Joyce Wieland: Heart On goes on view on Level 5 at the AGO. The exhibition is curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art at the AGO and Anne Grace, Curator of Modern Art at the MMFA. It is co-organized by the AGO and MMFA.

—

1. There are two scholarly discussions: Kristy A. Holmes, “Imagining and Visualizing ‘Indianness’ in Trudeauvian Canada: Joyce Wieland’s The Far Shore and True Patriot Love,” RACAR 35, no.2 (2010): 47–64, and Kristy A. Holmes, “Negotiating the Nation: The Work of Joyce Wieland, 1968–1976” (PhD diss., Queen’s University, 2007); and Matthew Purvis, “John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism” (PhD diss., Carleton University, 2020).

2. According to Anne Montagnes, “Wieland stated that, far from disputing sentiment, her feeling for the Arctic was love—realistic love. Behind the adulation was the knowledge that the Arctic is being raped.” Purvis, “John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland,” 296.

3. Susan Crean, “The Erotic Nationalism of Joyce Wieland,” This Magazine, August/September 1987, 17.

4. There were thirty-seven works on view: thirty-six works listed in Joyce Wieland, True Patriot Love / Véritable amour patriotique (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1971), plus Wieland’s artist book, also included in the installation.

5. Wieland, True Patriot Love, 29. This text is handwritten in the top margin of the page. It is also written in French, in the right margin, perpendicular to the English.

6. Joan Stewart, her sister, embroidered the flowers.

7. A.E. Porsild, Illustrated Flora of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, bulletin no. 146, Biological Series no. 50 (Ottawa: National Museum of Canada, 1964), 1. It was first published in 1957. Alf Erling Porsild was the chief curator of the National Herbarium of Canada from 1945 to 1967.

8. See maquette text in Joyce Wieland: Heart On publication, p. 194.

9. Crean “The Erotic Nationalism of Joyce Wieland,” 17.

10. Quoted in Debbie Magidson and Judy Wright, “Interviews with Canadian Artists: Debbie Magidson and Judy Wright Interview Joyce Wieland,” Canadian Forum 54 (May/June 1974): 61.

11. Quoted in Harry Malcolmson, “True Patriot Love: Joyce Wieland’s New Show,” Canadian Forum 51 (June 1971): 17

12. James Laxer, The Energy Poker Game: The Politics of the Continental Resources Deal (Toronto: New Press, 1970), 49.

13. Laxer, The Energy Poker Game, 35.

14. Mel Watkins, “Introduction” in Laxer, The Energy Poker Game, ii. Laxer and Watkins were leaders of the radical wing of the New Democratic Party, co-writing the Waffle Manifesto: For an Independent Socialist Canada in 1969. For a discussion of Wieland’s own association with the Waffle Party, see Johanne Sloan, “Joyce Wieland at the Border: Nationalism, the New Left, and the Question of Political Art in Canada,” Journal of Canadian Art History 26 (2005): 81–104.

15. A third of the pages of Porsild, Illustrated Flora of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, feature maps geographically locating the distribution of the plants across the Arctic.

16. The backs of the cushions are in red, yellow, blue, green, and pink fabric. Wieland’s description reads: “Arctic Day a quilt made of circular pillows (160 pillows in cotton) with coloured backing white tops—with drawings of Arctic animals, flowers, birds, insects—done with coloured pencils.” Wieland, True Patriot Love, 160.

17. Quoted in Kay Kritzwiser, “A Woman’s Work in the National Gallery,” The Globe and Mail, February 19, 1971, 13.

18. Kritzwiser, “A Woman’s Work,” 13.

19. Quoted in Magidson and Wright, “Interviews with Canadian Artists,” 63.

20. See the “Bloom of Matter” section in Joyce Wieland: Heart On publication, p. 212.

21. Wieland quoted in Magidson and Wright, “Interviews with Canadian Artists,” 63.

22. Wieland quoted in Magidson and Wright, “Interviews with Canadian Artists,” 63.

23. Hugo McPherson, “Wieland: An Epiphany of North,” artscanada, no. 158–59 (August/September 1971): 17–27.

24. See Leila Sujir’s text in Joyce Wieland: Heart On publication, p. 216.

25. Joyce Wieland, “Interview,” in Eclectic Eve, ed. Janice Cameron, Frances Ferdinands, Sharon Snitman, Madli Tamme, and Annetta Wernick (Toronto: Canadian Women’s Educational Press, 1972), unpaginated.